Science Fiction, Faith, and Catwoman

A reader with the golden name of Aurelian writes this letter:

Dear Mr. Wright:

As a fan of your science fiction writing, I’ve always wondered about the relationship between this particular aspect of your life and your religious beliefs.

Oddly enough, I have wondered about that too.

I would completely understand if any of the following questions are too personal in nature, but insofar as you would feel comfortable answering any of them,

I am pretty much immune to the reticence, sound judgment, and humility which makes artists unwilling to make fools of themselves in public, therefore let us proceed, no matter what the question!

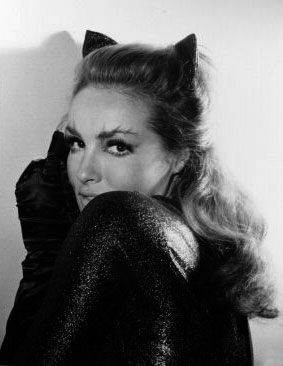

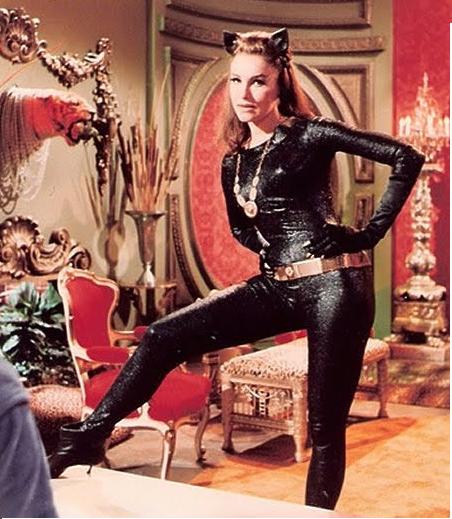

I assure you, the only topic I find difficult to talk about in public is my unhealthy obsession with Catwoman as portrayed by Julie Newmar.

I will agree gladly to answer any and all questions, no matter how painfully embarrassing, under two conditions: first, that you forgive me for answering bluntly; and second, we must never discuss my unhealthy obsession with Catwoman as portrayed by Julie Newmar.

We will not be Discussing the Exquisite Yet Evil Contours of her Perfect yet Blackly-Clad Villainous Body!

The letter continues:

… my questions to you would be:

1. Is science fiction in general (i.e. as a genre) in any sort of unique position to further traditional beliefs in God, and if so how?

Upon advice of counsel, my answers to the interrogatives are as follows:

Answer 1. If science fiction is in a unique position to evangelize either the Christian faith, or any number of traditional heresies, heathen, or pagan beliefs, I am not aware of it.

I have read books such as CS Lewis’ THE SCREWTAPE LETTERS which perform an admirable job of evangelism without being overly intrusive or preachy; but then again, one might say the same of Detective Stories, such as GK Chesterton’s ‘Father Brown’ stories.

Science fiction is able, by the nature of the genre, to set scenes in the afterlife, or the inferno, or paradise, or across multiple cycles of reincarnation, or have a ghost come onstage, all without disorientation to the reader — I am thinking of Heinlein’s STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND, or Niven and Pournelle’s INFERNO, but also of EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, all stories where ghosts are characters — but this is not unique to science fiction.

ALWAYS starring Richard Dreyfuss is a love story, as was GHOST starring Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore. WHAT DREAMS MAY COME starring Robin Williams is arguably science fiction or fantasy, but IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE, or ANGEL ON MY SHOULDER, or HEAVEN CAN WAIT, or THE BISHOP’S WIFE are in the same genre, whatever we call it, as HARVEY or BRIGADOON, when the fantastic element in the story is not fantastic enough to put it in the same genre as CONAN or LORD OF THE RINGS. Again, THE GHOST AND MRS MUIR is romantic comedy, and MY PARTNER THE GHOST is a detective show. For that matter, JONAH HEX is a Western.

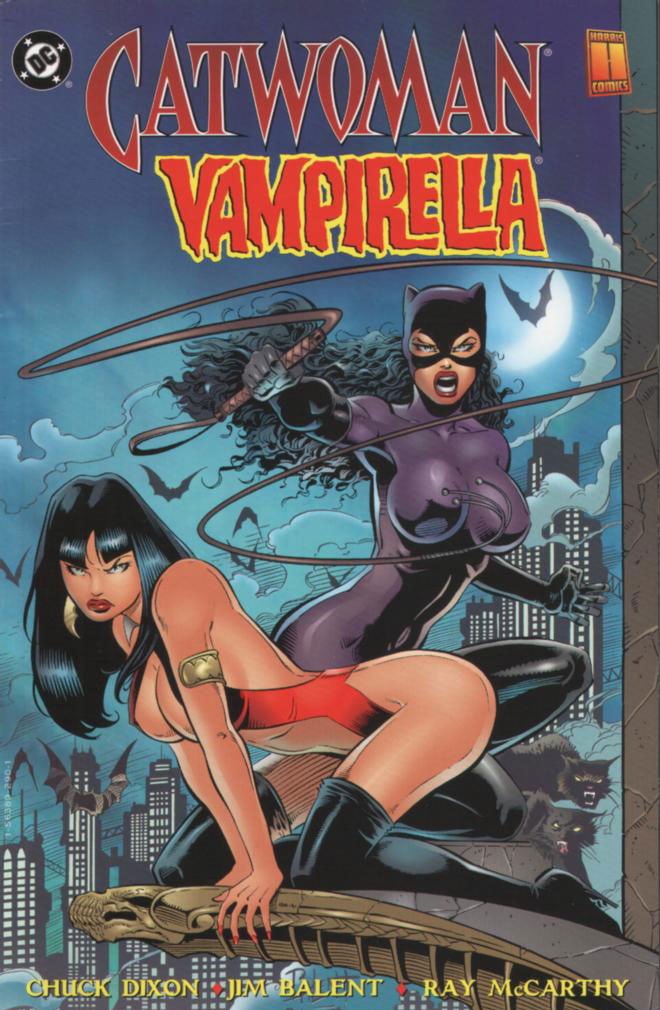

In superhero stories, there is an abundance of supernaturalism. I notice wryly that while the Marvel Universe is pagan, run by Gods of Asgard and Olympus and devils from Hell, and mystical beings like Eternity, the Living Tribunal, Master Order, Lord Chaos, the In-Betweener and so on, the DC Universe is clearly Judeo-Christian, since the Spectre is sent back to earth by the Voice of Heaven itself, since the Phantom Stranger is a wingless and exiled angel, and various supernal beings, as the Endless, encounter Seraphim and other Judeo-Christian figures. There were even comics where Ghost Teamed up with Batgirl, and Catwoman teamed up with Vampirella, mixing natural and supernatural cheesecake blithely.

Science fiction is in a unique position to undermine religious faith, however, since the basic assumptions and tropes of the genre requires naturalistic and scientific explanations for things. When you write magic into a science fiction story, it loses its essential ‘Forbidden Black Arts’ flavor and becomes and unsalted and bland science of psionics and parapsychology. If God comes on stage in a science fiction tale, he is most likely to be shot by Spock using a shipborne phaser cannon.

For example, in the novel THE BOOK OF PTATH (also published as TWO HUNDRED MILLION A.D.) by A.E. van Vogt, the central conceit of the book is that praying to a man through special ‘prayer sticks’ grants that man the godlike powers of immortality, astral projection, teleportation, possession, time travel. The story concerns the intrigue of an evil goddess consort Ineznia against her fellow goddess consort L’onee and against her lord and husband Ptath, reincarnated prematurely and without his memory. As space opera goes, it is perfectly fine boyish power-fantasies about superhumans. But the resolution of the plot hinges on one “secret” of human nature: that all religion, even if it pretends to be about adoration, is actually nothing but fear. A more shallow and cynical view of the religious experience and sentiment of mankind cannot be imagined.

I use this example not because it is extraordinary but because it is ordinary: the idea that religion is hooey is found in practically any science fiction book that touches the subject: I will mention GATHER, DARKNESS by Fritz Leiber, SIXTH COLUMN by Heinlein, FOUNDATION by Asimov (especially the section called ‘The Traders’), PLAYERS OF NULL-A by A.E. van Vogt; GODS OF MARS by Edgar Rice Burroughs (and its hentai knock-off PRIEST-KINGS OF GOR by John Norman); NIGHTSIDE THE LONG SUN by Gene Wolfe; THE CITY OF THE CHASCH by Jack Vance — all of these stories and many more concern gullible or ignorant worshippers bowing to aliens or to machines or to alien machines as gods. The gods in an SF book usually have a natural rather than a supernatural explanation, and the preferred explaination is the deceptions of priestcraft. As in Scooby Doo cartoons, the ghost turns out to be Mr. McGreedy from the Haunted Museum in a rubber mask.

Indeed, the whole point of science fiction (if I may be forgiven a rough generalization) is to take the monsters, gods, and magic of the human soul and reinterpret them as martians, energy beings, and sciences so advanced as to be indistinguishable from magic — with the crucial distinction that super-tech is NOT magic, because it works by natural laws not by supernatural fiat, and it has no moral component to it. The point of science fiction is to write naturalized and scientificized versions of the supernatural wonders of earth and sky.

To be sure, a skilled craftsman can blend the science fictional elements in a tale with elements from another genre, and write a SF comedy (as RED DWARF) or an SF Detective story (Niven, Asimov, and Bester have all done so) or an SF war story (STARSHIP TROOPERS, FOREVER WAR) or an SF horror (ALIENS) or an SF horror comedy (GHOSTBUSTERS).

There is nothing that prevents a science fiction writer from putting in his tale elements meant to edify the religious sensibilities of the audience, as CS Lewis has done so for orthodox Christianity, and as David Lindsay or Olaf Stapledon have done for Gnosticism (see PERELENDRA, VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS and STARMAKER). But this is no more easy for an SF story than for a pirate story, a western, a love story, or a detective story, and due to the innately naturalistic tropes of the genres, may be more difficult to do.

In my opinion, detective stories, war stories and horror stories lend themselves most easily to the tropes of science fiction. The detective and the scientist are the same archetype, the rational investigator; the inventions of future technology lend themselves easily to speculations about future war;and the alien nature of the unexplored, the edge of the map, is where monsters always dwell, whether a world map or a star map.

But the trope of the skeptical investigator does not blend easily with the trope of the childlike faith the pure in heart need to see God: fantasy, not science fiction, is the better venue for that.

And in a horror story, the scientist who says there is a rational explanation for the grisly murders in the empty house is always wrong. Likewise, in a superhero comic, the hero is just as likely to get his powers from a magic ring or a pagan god or a wizard named Shazam as from an exploded planet or atomic mutation. In these two genres, there is a bias in favor of supernaturalism, but for opposite reasons (in horror, the supernatural is inexplicable therefore scary; in superheroes, the supernatural is powerful, therefore awesome) whereas in science fiction, the bias cuts the other way. When we crave the wonder and romance that comes from a rational, scientific explanation, we turn to science fiction: when we crave the wonder from the irrational, mystical explanation, fantasy.

(This does not mean that every character in a superhero comic has a superpower, either supernatural or supertechnological. For example, Selina Kyle, the Catwoman, is merely a brilliant cat burglar, gymnast and martial artist. Her only ‘power’ is her villainous, villainess allure.)

Next:

2. To personalize the preceding question, if money were no object would you abandon science fiction writing and devote your time fully to religious and/or political argument, and if not why not?

Answer 2. I am not sure I understand the question. If money were no object? I used to work in a law firm. I had to take a pay cut to become a writer, which only supplements my day job by a small amount. I don’t write for the money.

The concept of not writing science fiction is one I do not understand. I mean, I understand the sentence, and the words are in English, but something in my brain cannot actually focus its attention on the meaning of the words. What is this “not write science fiction” of which you speak?

I have wanted to be a science fiction writer since I was roughly nine years old. I don’t think I read a single book not in the SFF genre until I was in my late twenties. I am, unfortunately, the only person I know who never changed his dream since age nine and successfully achieved it.

In all modesty, my science fiction writing is first rate. If I were not a Christian, I should most probably win awards for my writing. In all honesty, my political, hortatory, and persuasive writing is second rate. Chesterton and Lewis are better, as are any number of apologists and pundits.

So, if I understand the question, the answer is not just “no” but “hell, no.” I hope to die with my quill still so firmly clenched in my fist that the morgue will have to saw my thumb off.

However, I will from time to time continue to write insightful and reasonable arguments about important and serious topics of the day, such as, for example, why Catwoman is so desirable. I know she is evil, and yet, by Great Caesar’s Ghost, why do I find myself drawn to her?

Next question:

3. To what degree should one read your existing science fiction writing in terms of your religious beliefs?

Answer 3. To no degree in any way whatsoever. I am sufficiently skilled in my craft that the internal evidence of the books gives readers a notion of my personal opinions and beliefs only when I so choose.

Or so I hope. An insightful reviewer (that mythical beast rarer than a hippogriff) may surprise me yet. I recall reading one reviewer that caught every single obscure reference I wove into NULL-A CONTINUUM. Such a man might be able to deduce my psychological shoe size by reverse engineering my craftsmanship, but permit me to doubt the event until I see it.

The idea that readers or reviewers can discover me by reading my books is akin to a psychologist saying he can deduce Julie Newmar’s personality and opinions by watching the her portrayal of Catwoman on television.

There is some inevitable communication, to be sure, of what I think real life is like in any book. My own beliefs, of course, define what I think is realistic and unrealistic, but one is far more likely to discover what I think is dramatic, not what I think is realistic, by reading my humble space operas. Usually the moral or point of the story is something I myself believe, but not always.

Writers are a tricksy breed, my friend. We tell lies for a living. And I was a newspaperman before that, and a lawyer before that, professions well known for their adroitness at misdirecting the truth.

If I may boast, I once wrote a short story whose story logic required an explicitly religious ending — whereupon the editor, a witch, delicately asked me what faith I professed. I was an atheist at the time.

To that same editor I later sold a story set in the same background whose story logic required an utterly hopeless and ergo utterly irreligious ending, which I proceeded to write, despite that I was a Christian at that time.

Again, the religious themes in my book LAST GUARDIAN OF EVERNESS were so evident that at least one reviewer called it a work of Christian apologetic. This manuscript was written some ten years before I was able to sell it, well before my atheist philosophy had any fracture lines in its stern surface.

The only thing I did in that book was play as fair (or as unfair) with Christian myths as I did with pagan, but I did not express my personal opinion (which, at the time, was pro-pagan and anti-Christian). The poor reviewer, no doubt acclimated to the scalding over-pepper of Philip Pullman could not taste my subtler but just as irreligious hint of spice.

Or, worse, because I was a Stoic, and actually believed in old fashioned notions like good and evil, virtue and vice, and in right reason, the reviewer (no doubt weary from dancing naked at a Black Sabbath and listening to the rock band of the same name, and servicing his drug-frenzied orgiastic meneads, head spinning from the sacred opiates, and arms aching from smashing stain glass windows with his electric guitar) could not tell the difference between a follower of a virtuous pagan philosopher like Marcus Aurelius and a follower of a Christian apostle like Saint Paul, even though Aurelius the Stoic burned Christian apostles. From the post-Christian point of view, every form of inquiry into truth and virtue is equally hated and scorned as the eructations of fundies — but now I am doing what I warned you against, and guessing the inner workings of a reviewer’s heart from his outward trail of wandering ink.

On the other hand, NULL-A CONTINUUM was written after my conversion, but if anyone reviewer claims to find the least trace of any philosophy in that work aside from the optimistic secular triumphalism philosophy of A.E. van Vogt, I will politely laugh with disbelief.

“For example, the first time I read “Guest Law” I found myself wondering whether you saw the crew of the “Procrustes” as representing maintstream culture, and the stranger “Descender” as representing you.”

Answer 3A. The stranger “Descender” is Zeus, who enforces the guest law. The crew of the ship Procrustes are Procrustes, the famed mythical figure who murders his guests.

I do not recall describing “Descender” as being a balding, over-weight, near-sighted, over-bearded curmudgeon with an unhealthy fixation on Catwoman as portrayed by Julie Newmar, but perhaps you are seeing more in the text than I consciously intended.

Continuing:

Similarly, in reading “The Far End of History” I found myself wondering whether the emergence of the new beings who ultimately hosted the Great War’s refugees was meant to represent you and your wife.

Answer 3B. Eh? You think I am a taciturn and self-disciplined space soldier? You think my wife is a Lady of the Silent Oecumene, a creature of immense power devoted to irrationality? I don’t know whether to be flattered for the honor done to me or discombobulated over the dishonor done my wife.

Tommy Atkins is taken from a Kipling poem of the same name. Once again, I did not bother to hide my intent.

No, you have it all wrong. Clearly the Lady of the Silent Oecumene represents Catwoman as portrayed by Julie Newmar.

Moving right along:

And finally, I wondered whether the emergence of the hero’s “ring” into full personhood toward the end of your “Golden Age” trilogy was intended to express a position on the sacred nature of life before birth.”

Answer 3C. Nope. I was an atheist when I wrote that scene, and held nothing to be literally sacred.

As an atheist, I did hold that integrity was “sacred” in the sense that it is not a value meant to be weighed on a scale against other values, nor discarded when inconvenient.

That scene sprang from the logic of the story, since a society which did not care for its young (in this case, electronic or artificial young) cannot thrive and might not survive. I regard this merely as a logical deduction, or, if you will, an expression of the integrity of my imaginary libertarian commonwealth of the far future.

Do any of these interpretations of your writing have merit?

Answer 3D. Not to my knowledge, not even a wee little bit. Sorry to be blunt, but I did agree to answer your questions gladly.

Your analysis fell short only because you did not take into account the cardinal, if not pivotal role that Catwoman plays in my psychology and ergo in all of my works of fiction. I feel myself somehow drawn to her, albeit I know she merely means to entangle me in her web of sin.

In any case, all kidding aside, I am pleased and astonished that you both read my tales and liked them. I could not even get my Mom to read both of them.

In any case, let me say that I’ve enjoyed your writing considerably over the years, and feel it represents a unique voice:

Yes, so far, I have uniquely written in the unique voice and backgrounds of A.E. van Vogt, Jack Vance, and William Hope Hodgson. I agree that my ability to blend into the crowd makes me stand out from the crowd. Er… wait a sec …

… themes of heroism and certainty are obviously a refreshing counterpoint to the fatalism and cynicism which seems to imbue much of science fiction writing today.

I cannot think of any snappy comeback or dumb joke here, so let me just be humble for once and say thank you. I write the kind of books I’d like to read, except longer, and I don’t even get the notion of reading about dipsomaniacs, street thugs, and punks, cyber or not.

As such, I hope that regardless of where your career, success, and personal interests may take you, that you will always find time to write at least one or two short stories a year.

Well, my next manuscript JUDGE OF AGES is due at the editor’s desk in six weeks, and I still have to figure out how to smash an asteroid into the Eastern Hemisphere, construct a giant stalactite leading from the mantle to the core peopled with a civilization with more land-area than the surface of the earth, and battle the computer entity that has taken over the nickle-iron core of the planet, not to mention portray the events of the warlike Chimera of AD 4000, the luscious Nymphs of AD 5000, the sinister Hormagaunts of AD 6000, the Locusts of AD 8000 who supersede them, and the Melusine of AD 10000 who supersede them, so that when they all wake up from cryogenic suspension, along with Giants, Sylphs, Savants, Cyborgs and electronic Ghosts, everything can erupt into a satisfying donnybrook of epic proportions.

And of course I want my future-Texan roughneck, supergenius and badass Menelaus Montrose to get into a duel with rocket-pistols with my arch-villain Ximen “Blackie” del Azarchel, self-styled Master of the World and of the Hermetic Order; for the two men are fighting over Space Princess Rania, who alone has deciphered the alien Monument circling the star whose core contains a multi-doudecacillion caret degenerate-matter diamond. Menelaus will be aided by his trusty power-armor wearing sidekick Sir Guiden of the Ancient and Honorable Military Order of the Knights Hospitalier of Jerusalem, Rhodes, Malta and Colorado. (Both the sidekick and the armor are trusty, so read that last sentence either way.)

I certainly enjoy the flattering opinion you have of my work, but I have to report that I am merely taking dictation from a higher power, if it a shining muse, or a lower power, if it is my turgid subconscious mind. Take your pick, depending on your world view. So the only credit due me is my diligence in getting the darn thing written down — diligence which I offend by pausing to write orotund answers to fan mail.

But I thank you for the pleasant distraction and the pleasing words. And now back to work.

If only I could concentrate, and drive the alluring yet tormenting images of Catwoman from my dazed yet feverish brain! And what is it about her I find so irrestable? Hmm. Let me think… I am sure if I ponder long enough, I can put my hand on it….

NOTE TO THE HUMOR IMPAIRED: The frequent references to my unhealthy obsession with Julie Newmar’s portayal of Catwoman is, of course, just a joke. First, I am in a twelve-step program, and only obsess socially, and only on the weekends, and I could quit at any time.

Second, I am not obsessed with Julie Newmar’s portrayal of Catwoman, that is, not since I found out Ann Hathaway will be portraying Catwoman in an upcoming movie: