You’ve Come a Long Way Down, Baby: The Tao of Housework

There is an ongoing discussing on the comments thread of this piece You’ve Come a Long Way Down Baby! which I should like, for purposes of legibility, to move to its own topic.

For those of us who came in late, the beginnings of the debate was this:

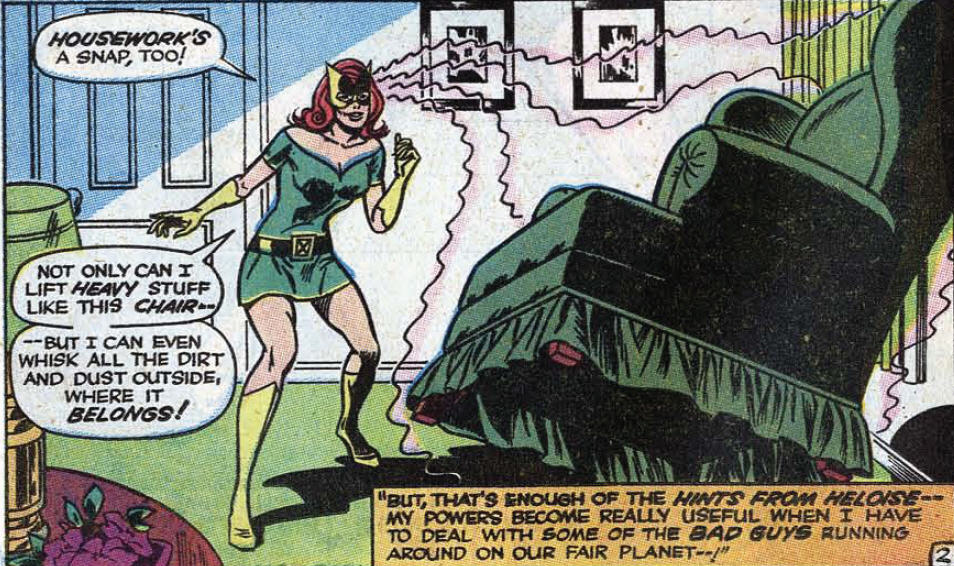

The original post reprinted this panel from a comic, which, I submit, and no one has denied, the average modern reader finds mildly or acutely embarrassing (and the modern feminist reader finds outrageous and blasphemous) because it portrays a superhuman girl as a girl who does housework when not engaged in world-saving, a girl who voices no shame over this stereotypical feminine role.

In the original post, I had proposed (1) that it is the negative emotional reaction of the modern reader to this panel (ranging from mild embarrassment to acute rage) is wrong because false-to-facts, a neurotic rather than healthy; and that the opposite emotional reaction of approval is true-to-facts and right and normal and (2) it is natural because expected rather than arbitrary (or sinister) to associate housework with keeping house with motherhood with femininity, and that the emotional association or link between the two, if touched upon at all in popular entertainment, ought to be encouraged rather than discouraged, because the felicity of mankind is served thereby.

When questioned, I had written this (numbering not in the original).

1. Humans are altricial mammals.

2. The female of the species, the one associated with ideas of femininity, gives birth and gives milk.

3. This makes it naturally less difficult for the mother to nurse the baby than the father.

4. Babies are small and delicate, and not to be toted from place to place unnecessarily.

5. This makes nursing in the nursery less difficult than taking the baby abroad to nurse.

6. The nursery is usually (because it is less difficult) in the same structure, be it a house or wagon or cave, where the sleeping and eating arrangements are made.

7. If mother wants to put baby down in a clean as opposed to dirty spot, it is easier and less difficult to clean it herself than to call the father, who is, in humans, on average the taller, stronger, and more aggressive of the pair, back from whatever hunt, field labor, factory or office work consumes his time to feed the family to come clean it.

Hence, again, it is natural, because it is easier, for fathers to be more concerned with the field work or factory work on which they concentrate than on house work, which is the concern of the mother.

A society can chose to teach that these roles are acceptable or teach that they are not. The comic comes from a time when teaching that these roles are acceptable was also acceptable. The current society, it is not.

A reader and longtime often (but not always) honest debate partner, Rolf Andreassen, writes in to dispute the point. He says:

We were discussing, first, whether it is natural for women to be more attracted to housework than men are; and second, whether they should be encouraged to do so; or to put it differently, whether tending the home, as opposed to working outside it, is particularly feminine, and whether women should be encouraged to be feminine. Now, I do not think I disagree with you on the second point; it is not good for humans to be androgynes. So we are arguing over what femininity means; and we may note, perhaps, that it is not a simple thing any more than masculinity is, and that even while encouraging femininity one may emphasize some aspects over others. At least, this is what I thought we were arguing about; do you agree so far?

Now, on housework: I submit that your argument from altriciality is invalid, because tending a modern house bears no resemblance to what our female ancestors did. In particular, a nomad hunter-gatherer band has no home, as such; only campsites, to be constructed afresh daily. Further, although men may range further afield for the hunt, women still go out of the campsite to gather plants, taking with them any children too young to walk. I therefore conclude that considering housework to be feminine, and outside work to be masculine, is a modern construct not based in the respective natures of the genders, but rather on the economic factors of earlier centuries – in particular, the need for upper-body strength in farming and early industrial work.

Robert Mitchell Jr has already voiced an objection that naturally occurs to the core unsupported assertion of Dr. A’s statement.

First, your postulate that tending a modern house “bears no resemblance to what our female ancestors did” is unsupported or wrong. Are you saying that our female ancestors did not stay closer to the home to nurse and care for the children? Are you saying that being able to move your shelter keeps it from being your home?

Andreassen’s reply was a non-sequitur that need not long delay us. He said that the domestic chores of female ancestors did not much resemble vacuuming, washing the dishes, and polishing the silverware. He said that a nomadic lifestyle obviated the need for housework, because if you move every two weeks, the nursing parent need not clean a spot to put the baby down when nursing was done; Cleaning is a habit of settled peoples.

All in all, he simply did not answer Mitchell’s objection, which was that nursing and mothering the young is essentially the same in industrial, agrarian, and nomadic societies, and that the differences are surface features inconsequential to the argument. It is not an answer, indeed, it is practically an admission, to point to inconsequential surface features when the argument is about whether humans are mammalian and altricial, therefore mothers are generally more naturally suited to mother the young, and that it is easier for mothers to do the domestic chore which are at hand rather than calling in the father from his chores abroad.

Andreassen then says that being able to move your tribal camp or gypsy wagon or Neanderthal cave every two weeks means that no one ever does domestic chores. We can safely dismiss this unsupported assertion with a guffaw. Even if true, it has no bearing on the argument. That one does not find women doing “housework” in those prehistoric times before humans lived in houses is not to the point. To prove what no one has denied proves nothing. So let us count the score in favor of Mitchell, and return to the main course of the argument.

Andreassen asks whether he and I were discussing whether it were natural for women to be more attracted to housework than men are. My answer is no. That is not what we were discussing. I said nothing about attractiveness. Who likes chores? We were discussing whether it was healthy to have a negative emotional reaction to portraying women doing housework as a normal thing versus an abnormal, hateful or repugnant thing.

Andreassen asks whether he and I were discussing whether women should be encouraged to tend the home, as opposed to working outside it. My answer again is no. I said nothing one way or the other about working outside the home. I did say it was neurotic to encourage men or women to regard women’s work as dishonorable, but this was in the context of a slightly different discussion.

Andreassen asks whether he and I were discussing whether tending the home is particularly feminine. My answer is yes. Housekeeping is women’s work for the same reason working as a field hand or factory hand or as an office clerk is men’s work. This is generally the expected work to be done by the mother and father in a family, and for the good reason that the sexes are generally suited each to his task, or, if you prefer, the chores suited to the sexes. There are exceptions that defeat these expectations. But we were not discussing whether the exceptions exist: we were discussing whether the mere act of having normal expectations is wrong.

The only argument presented so far is that the normal expectations don’t exist. Since this denies the primary fact under discussion, I don’t know what to make of the assertion. I suppose Andreassen could make the argument that the expectations should not exist because it is not natural or normal or expected for wives to be mothers, or mothers to nurse, or nursing mothers to have a nursery or spot set aside for baby. I suppose he could make the argument that nursing a crying baby can be done just as efficiently at home as at work, while mom is serving as a fireman or fighterpilot or miner or lumberjack — assuming these tasks can be done one-handed, perhaps with baby in a sling or backpack — but that is not the argument he made. He did not say the conditions that make mothering during work hours difficult exist but should not; he said the conditions did not exist. Perhaps I misunderstand his point.

Andreassen asks whether he and I were discussing whether women should be encouraged to be feminine.He then says he does not disagree on that point, reserving that we may differ as to what is defined by that term. Granted.

Andreassen asks whether he and I were discussing what femininity means, given that he concept is not simple, and that there are aspects which may emphasize one over the other. To that I cannot reply because I don’t understand the sentence. He seems to be making a statement rather than asking a question. If so, it is not relevant. No matter how complex and subtle the question, all I need show for my argument is (1) that it is not arbitrary or sinister to associate femininity with motherhood (2) motherhood with home-making (3) home-making with housekeeping chores. And I must further show that it is better for society to encourage these associations and expectations rather than discourage them.

Andreassen’s main assertion that comes next is this:

I submit that your argument from altriciality is invalid, because tending a modern house bears no resemblance to what our female ancestors did.

Since I did not make any statement about what our female ancestors did, as best I can tell, this assertion is unrelated to the discussion. My argument was that the concept of femininity is related to the concept of motherhood because only females can become mothers, and that motherhood was related to domestic chores because human babies are delicate enough that it is better not to tote them from place to place if this can be helped, and furthermore that it is inefficient to call the menfolk back in from the field or sheepfold or silvermine or whaling ship or battlefield or office building to do domestic housekeeping if the mother is already in the house, which is usually where the nursery is.

I therefore conclude that considering housework to be feminine, and outside work to be masculine, is a modern construct not based in the respective natures of the genders, but rather on the economic factors of earlier centuries – in particular, the need for upper-body strength in farming and early industrial work.

The word “therefore” in this sentence links two concepts whose relation I do not see. I am not sure what is meant by “construct” modern or not, unless he means it is a falsehood.

But since every mother I know lives in a house, and a modern one, not one of which has a robot maid nor is self-cleaning, whether housework is a modern construct or not has no bearing on the current argument. We are talking about women in general and modern women in particular. Likewise the mention of upper body strength is irrelevant here, as is the mention of economic factors. The factors are either the same for the range we are discussing, or irrelevant.

Even if we viewed this argument in the most favorable possible light, and granted its unsupported assumptions as given, it would not refute, nor even speak to, my argument, which is that femininity is naturally associated with motherhood, which is naturally associated with domestic life, and domestic life with domestic chores.

So we are at something of an impasse, or, at least, it looks to me as if we are discussing two different topics. Let me see if it might help to restate the original point in stronger and clearer terms.

* * *

My contention is that the emotional association between femininity and motherhood and typical motherly tasks or “woman’s work” is as normal and as generally benevolent as the emotional association between masculinity and fatherhood and typical fatherly tasks.

(I say “generally”, because I admit there are exceptions; I say “as benevolent” because I can think of some drawbacks to a society that has and teaches some expectations. It is not a cost-free proposition.)

That being so, I see nothing sinister or risible in funnybook readers being presented with images of superheroines doing thankless housework, no more than images of Clark Kent or Peter Parker performing their thankless jobs for their bosses — both of whom (Perry White and J Jonah Jameson) are stereotypically short-tempered, I should add. Great Caesar’s Ghost!

I submit the belief that motherhood and homemaking is dishonorable is not only a false belief, erosive of the felicity of mankind when put into practice, as it has been at least in America (I cannot speak for any other nation). The sum effect is to make women with the normal and honorable ambition to be wives and mothers suffer public shame.

I know more than one young office-woman of child-bearing age (but getting older too rapidly) who will admit to me in whispers, but never in public, that she wants to be kept barefoot and pregnant in the kitchen, or longs for domestic life, chores or no chores. Changing diapers is not less rewarding than Bates’ Stamping or typing up depositions or other routine and repetitive office work. At least when the diaper is changed, you have a clean baby it is rewarding to fondle and dandle.

In an earlier conversation, it was mentioned that women whose children are away at school therefore have no pressing domestic chores, thanks to modern automation, to keep them at home. Whether true or not, this has no bearing on the question of whether society should wince at the sight of Marvel Girl doing housework. Even if housework only occupies the few years of a semi-sterile couple blessed with far fewer children than Priam, after which Mom, now gray and worn, can be returned to the factory floor to toil and sweat for the reward of supporting the tax-eating class, corporate welfare and public sector union bosses, this provides no reason why calling housework “woman’s work” should provoke an allergic reaction of embarassed revulsion. The two lines are argument are again unrelated. Merely because automation makes domestic chores easier and fewer does not logically make it morally correct to despise such chores nor to regard it as misogyny for society to regard it as normal and expected that mothers do them rather than fathers.

Women who think work as office clerks or field or factory hands offers some tremendous spiritual reward or personal gratification have had many post-suffragette years of experience to learn otherwise.

Most working men hate Mondays. I have not heard it was all that different for working women.

The fashionable modern belief is an association made between the concept of motherhood and the concept of evil masculine oppression of the weak and helpless female victim. This association is false, wicked, neurotic. It is not merely disconnected from reality (false), but provoked by a malicious hatred of reality (wicked) with a corresponding denial of reality (neurosis).

If any one wishes to claim that motherhood is universally despised, this is as far from my experience of real life as the claim that the earth is flat or that the moon landing were faked up on a sound stage. It is conspiracy-theory gibberish.

If any wish to make the case that this is so, and that my mother and my wife and every married woman I know are not are secretly being oppressed by me and my sex without my knowledge, consent, awareness nor any proof of that oppression being before my eyes, since he is making an unusual claim, he will need to unusually convincing proofs.

I should mention his proof has to be so brilliant and self-evident that it also must overcome the bias of my youth.

I was raised on post among Naval officer and men, who were absent for months out of the year. The Navy Wives ran their households and neighborhoods, and there were no more men present than in Themyscira, the ancient capital of the Amazons. The husband’s paychecks came to the wives, and the men had no ability to spend a dime of it while at sea. The sacrifices the husbands made by spending their lives in military service, often without even seeing the family for months or years, were routine, and never in my hearing was a single word of complain voiced. The notion that the servicemen enjoyed independence of being the breadwinner at the expense of their longsuffering wives does not match my experience of those times. (I say nothing of the modern Co-Ed Navy, since I have no inside knowledge it.)

If anyone wants to make the argument that the typical modern male is not married to the mother of his children, and does not support them, and that the woman both works out of the house and does most or all of the housework, and therefore teaching that the stereotypical sexual roles is now outmoded or outdated for young urban professionals either with no children, or who deny their children to be raised by their mother in order to have a second income, I do not argue that point: That a sick society must teach sick values to maintian its sickness I do not dispute. I merely dispute the idea that sickness is as desirable or moreso than health.