Vanvogtian Vision vs Campbellian Cosmic Mechanics

Here is an excellent essay on the early work of A.E. van Vogt: Man Beyond Man by Alexai Panshin.

I urge those readers who are fans of A.E. van Vogt to read it. Those readers who are not van Vogt fans, I urge you to become so at your earliest convenience.

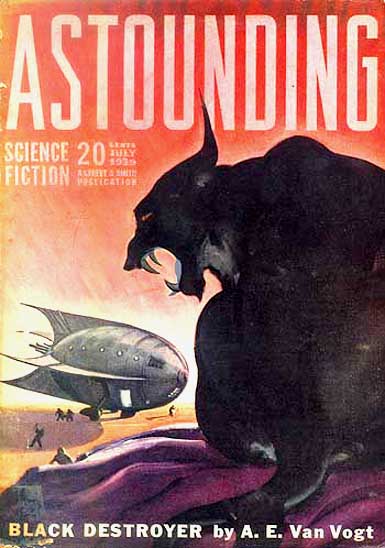

Mr Panshin discusses Van Vogt’s early short stories and novels, from ‘Vault of the Beast’ to ‘The Black Destroyer’ to SLAN to ‘Resserection’ to the Weapon Shops of Isher short stories, ‘Asylum’ and ‘Proxy Intelligence.’ These include some of the very best of van Vogt’s work, and personal favorites of mine.

Mr Panshin emphasizes a holistic and moralistic idea guiding van Vogt’s writing which he contrasts (favorably) with the more mechanistic idea guiding John W Campbell’s editorial work. The Campbellian reductionist materialist idea envisions the universe as a massive but unliving mechanism, a Sampo set to grind out prosperity and power to whomever should first discover the rulebook for its operation. The Vanvogtian vision is that the universe, including man, is a living and organic and mutually interdependent system, one where altruism and far-sighted cooperativeness form the key to understanding.

I wish I had read this essay before I sat down to write NULL-A CONTINUUM.

Reading it now, I note the several places where NULL-A CONTINUUM had, not by the author’s intent yet not by accident, fallen neatly into the pattern established for a Van Vogtian theme.

This thematic parallel between a sequel and its originals should not come as a surprise. The Vanvogtian theme of an organic unity of the universe cannot be avoided by an epigone (like myself) who accurate copies his master’s model.

In my case, the explicit driver of the plot in NULL-A CONTINUUM was that the self-aware universe, including man, was and had to be self-aware at an ultimate level, that is, to be Null-A trained: the goal was that the insane universe had to be evolved or trained to sanity, and to embrace absolute altruism, even to the point of the self-sacrifice of the continuum for the sake of the greater good. With that plot driver, I could not have avoided engaging the Vanvogtian master-theme of cosmic unity correctly.

Contrast this with Damon Knight’s deservedly obscure BEYOND THE BARRIER. Mr Knight was something of an antagonist to Van Vogt, dismissing his work as deamlike and illogical, and BARRIER was Mr Knight’s attempt to do a Vanvogtian pastiche. But by failing to copy the central theme that Mr Panshin identifies, Mr Knight’s yarn fails. All the trappings of a Vanvogtian plot are present (amnesiacs, time paradox, aliens in disguise) but the end result is dismal.

Contrast this again with THE PARADOX MEN aka FLIGHT INTO YESTERDAY by Charles L Harness, the best Vanvogtian book never written by van Vogt: I suggest that hints of the theme of the unity of the universe are present there, particular in the time paradox that forms the title of the book.

Consider the famous plot reversals typical of van Vogt, where what seems to be an implacable foe (such as Keir Gray, the world dictator in SLAN) turns out to be a leader or even a mentor, or where two enemy forces (such as the Weapon Shops and the Imperial House of Isher) turn out to be necessary mutual components of a ying-and-yang wheel. Mr Panshin argues that these reverses are not mere “twists” or sleights of hand, but a deliberate theme by Van Vogt to show the reader (or, better, to have the reader experience) that sudden expansion of awareness by which a selfish and isolated individual learns he is part of a greater universe, so that the farthest star is touching his heart, and the smallest gesture of kindness or cruelty reflects and affects a cosmic war of enlightenment versus ignorance.

The climaxes of Van Vogt tales are rarely if ever fight scenes. Instead, they are scenes of revelation, even apotheosis, where the perspective on all that has gone before undergoes a paradigm shift.

These revelations, oddly enough, are of precisely the opposite character as similar revelation scenes in HP Lovecraft, or even in a tale like ‘Nightfall’ by Isaac Asimov, where the inhuman immensity of the universe drives man mad: the protagonist sees what can only be called a human immensity.

Mr Panshin also emphasizes in Man Beyond Man a theme mentioned in his essay on Robert Heinlein (The Death of Science Fiction A Dream): Van Vogt, of all the Campbellian stable of writers, comes closest to portraying the step beyond human evolution, and not as the cold-hearted big-headed hyper-rationality of the Martians of H.G .Wells, or the reptilian amorality of the superman of Nietzsche.

What an awesome challenge it was for van Vogt to attempt to imagine the likes of a fully integrated Great Galactic! As a gauge of how difficult it could be in 1941 to conceive of an encounter with a radically transcendent being, we might remember Slayton Ford returning a broken man from his interview with the gods of the Jockaira in Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children,or the brief, unrecallable glimpse of a High One in Heinlein’s “By His Bootstraps,” which demoralizes Bob Wilson/Diktor, turns his hair gray overnight, and leaves him feeling like a bewildered collie who can’t fathom how it is that dog food manages to get into cans.

But it wasn’t just a less traumatic meeting with radical superiority that van Vogt was proposing to imagine. What van Vogt aimed to show was nothing less than a normal Earthman — or something like one — being transmuted and melded and assumed into the highest state of awareness and responsibility that the writer was capable of conceiving.

This awareness of the organic interconnection of the cosmos is not a knowledge needed to conquer the universe (one organ in an organism does not conquer the others but cooperates with it) but it is the knowledge, in the vision of van Vogt, to open the gates to the future.

To act without that knowledge is fatal. In NULL-A CONTINUUM, the attempt by Gilbert Gosseyn in the final chapter to overcome the exo-multiversal enemy Ydd by destroying it creates the cosmic disaster he had been trying to avoid–the organic unity of the cosmos is a theme in the book, but not one consciously imposed by the author.

The self-destruction of the main villain in NULL-A CONTINUUM was based consciously on the themes from THE VIOLENT MALE van Vogt’s one mainstream novel and his most obscure work: the parallels to the self-destruction of the Courl and the Ixtl in VOYAGE OF THE SPACE BEAGLE and the more grotesque self-destruction of the Kibmadine in THE SILKIE was not intentional, but, of course, followed the same pattern, the same logic of theme.

And likewise, the ending of NULL-A CONTINUUM was based closely (actually, word-for-word) on the ending of ‘Asylum.’ This was not merely based on a lazy writer’s wish to copy the original, but also because the theme logic allowed for no other ending.

By them logic I mean this: If you are writing a story about the interconnectedness of all things, you cannot have the ending be anything other than a revelation of that interconnection–ergo the arch foe called “X” as well as the benevolent father-figure Lavoisier, as well as the golden giants from the remote future and the primal “Ptath” from the remote past, have to be part of the same oneness.

One reviewer was taken aback that I introduced a “warped” version of the Null-A training into the universe, and erected Loyalty Machines in the place of Games Machines. But like the Prof Kenrube’s hyperspace machine in “Secret Unattainable” a Vanvogtian machine which is part of the cosmic organism affects and is affected by the mind of those who use it, especially where this is a psychological teaching machine. The parallel with Kenrube’s machine was unintentional but not mere accident. The same philosophical concept was at work in both tales: in a Vanvogtian universe a mechanism tied to the very fabric of reality must correct itself in the direction of sanity, that is, of congruence with reality.

Despite that I had not read this essay before writing my book, nonetheless, the spirit of Van Vogt guided my theme even if I did not fully or consciously recognize it. (Or the muse, or my subconscious, or the innate logic of the plot, or my love for his works, or whatever one wishes to label it.) And for that I am grateful.

What I think is odd is how much I enjoy writing in other’s men’s worlds more than in my own. While this may be because I am more suited to fanfic than the true creativity; but on the other hand, this may be because all human beings, except those afflicted with narcissistic disorder, take more joy in the others’ works than in one’s own.