Retrophobia

I read two posts recently that touched on the same topic, namely, the way writers handle female characters in historical fiction and heroic fantasy.

Both reinforced my opinion that Political Correctness is, at its root, undramatic and the enemy of the arts in the same way it is illogical and the enemy of science and reason, namely, because it is ahistorical and inhuman.

The first one reinforced my opinion by arguing in favor of the proposition that egalitarianism, here understood to be strong female characters whose strength was physical, not emotional or spiritual, was unrealistic as well as undramatic.

Alpha Game writes (http://alphagameplan.blogspot.ca/2012/12/its-not-historical-if-its-not-sexist.html)

The problem with what Wohl advocates is that by putting modern views on sexual roles and intersexual relations into the minds, mouths, and worse, structures of an imaginary historical society, it destroys the very structural foundations that make the society historical and the dramatic storylines credible – in some cases, even possible.

It’s problem similar to the one faced by secular writers, who wish to simultaneously eliminate religion from their fictional medieval societies, and yet retain the dramatic conflict created by the divine right of kings.

However, it is more severe because the sexual aspect touches upon the most concrete basis of every society: its ability to sustain itself through the propagation of its members.

[…]

Do you want massive battles between civilized cultures? Then most women had better be at home raising large families capable of providing the men for the armies and the societal wealth to support them.

Do you want dynastic conflict? Then you need mothers married to powerful men producing those dynasties.

Do you seek the dramatic tension of forbidden love? Then someone had better possess the authority to credibly forbid it.

…if you contemplate the matter, it should rapidly become obvious that the insertion of modern equalitarianism into quasi-medieval fantasy is less credible and more dramatically devastating than giving the occasional knight an M16A4 assault rifle. The assault rifle is merely ridiculous whereas the equalitarianism undermines the logical basis for the vast majority of most historical conflict. And while there are ways to work around these issues, (the knight with the assault rifle is a time traveler, strong independent warrior women drop large litters of children by the roadside that are gathered by good-hearted monks and mature in six months), the point is that if they are not addressed in an intellectually competent matter – and they usually aren’t – the result is doomed to be an incoherent, illogical mess that will have to be very well-written to even pass for mediocre.

To which I merely say, Amen, and hear, hear.

As someone with much experience with women who show more courage and fortitude on a spiritual level than most men, and as a man who would be lost without the spiritual support of his wife, I am not only nonplussed, but bewildered at the vanity and folly of yearning to be physically stronger than men.

What is the point of feeling insulted if you see a King Arthur movie, and neither Guinevere nor Morgan le Fay picks up a sword? Guinevere had more power than Lancelot, who was far stronger than her physically. She could destroy a kingdom by smiling at Lancelot. And Morgan le Fay could destroy a king.

Envy does not have a logic to it; it is not content to be strong in one area only; it brooks no rivals, it allows no debate, no dissent. So the princess in a modern yarn has to be not only pretty as Helen and chaste as Penelope and bold as Clytemnestra, she must be as strong as Beowulf, Sampson, and Hercules.

Alpha Game is speaking to this. He is, in the passage quoted above, talking about the ‘woman warrior’ or ‘martial maiden’ trope, not about the idea of a queen or female captain leading warriors in combat, which has happened in real life in the real world, a la Joan of Arc or Semiramis.

To be sure, the ‘martial maid’ is an ancient trope in literature, and harkens back to Britomart in FAERIE QUEENE and Brandomart in ORLANDO FURIOSO (unless I have those two reversed) or Camilla in the AENEID, and even figures like Athena and Hyppolita the Amazon.

What we, who live in a day and age when women serve in the military, tend to forget is that for every previous generation the sight of a woman in armor was somewhere between cute and ridiculous, and that the Amazons were no more realistic that the Hydra, or Dame Brandomart than the hippogriff who flies to the moon. In no sense were these ancient and Renaissance models of ‘martial maidens’ images of genderless military egalitarianism.

Either they were monsters which delighted the imagination because of their exotic strangeness – Amazons were as peculiar as the pygmies which made war on cranes – or they were symbols. Athena represents, among other things, the virginal purity of a chaste reason, a mind that does not prostitute itself, combined with the beauty of philosophy, the warlike nature of reason that battles lies and errors, and holds the divine lightningbolt of sudden insight.

As for women warriors, I note with particular pleasure an anonymous comment attached to Alpha Game’s article:

I think these woman-warrior types should have to train with men for at least 5 classes in the contact martial art of their choice. If nothing else, they’d learn how to write better fight scenes, and they’d also learn a few inconvenient truths about male strength. I have been holding the square padded target and had a man’s blow to same turn me completely around. Now imagine that same guy, not your gentlemanly training partner, but filled up with adrenaline and intent on killing you.

My opinion is that, as with most things in storytelling, the execution matters more than the material.

Let me digress to explain that, because it sounds at first absurd. Storytelling is the art of casting a magical spell to enchant your audience so that the false story you are inventing will seem real, if not to the listener, at least to his imagination. Science fiction and fantasy (if I may boast for a moment of my dear readers) requires more imagination on the part of the audience because not only is the story an invented make believe, so is the whole world in which it takes place. Historical fiction requires imagination to a smaller degree, as does fiction set in exotic locations.

The magic spell is beautiful and brittle like glass. One wrong word can shatter it. I have been happily reading a ‘magical realism’ story set in the 1960’s upstate New York, and then the author gives a date not in A.D. but in A.C.E., a terminology no one used in the Sixties, and which was obnoxiously politically correct. Even though I was on the last chapter of a four book series it had taken the author decades to write, it was too late. The spell was broken. I realized I was not in the magical faraway hills of New York in the Summer of Love, but listening to crap propaganda from an enemy of Christ who was so bitter against Christendom that he could not even bring himself to refer to the Gregorian calendar honestly. I was yanked out of that mysterious fairyland back into the quotidian realm. Even though I had only a chapter to go, I put the book on the shelf, and have not been able to bring myself to open it again.

By way of contrast, THE WORM OUROBOROS by E.R. Edison employs the most overly rich orotund Elizabethian style imaginable, and sustains the tightrope walk of speaking in elevated language across hundreds of pages and thousands of words without a misstep. The only writer with a more perfect mastery of language is J.R.R. Tolkien, who can segue from the elevated language of kings and elves to the coarseness of orcs to the rustic simplicity of hobbits without faltering, and he does this so effortlessly that the reader may not notice it on his first reading. Of course, everyone I know who has read the LORD OF THE RINGS has reread it many times.

The magic spell works by lulling the dragons of disbelief. In science fiction this lulling is done by drawing on the prestige of science and the uncertainty of the future. The future is to us like Africa or Mars was to his audience in the day of Edgar Rice Burroughs: we know something of what is there, but mostly the map is blank.

By the prestige of science, I mean only that we as readers are willing (at least for the sake of the story) to believe in warp drives and time machines on the grounds that, even though we all know time machines don’t exist, in our forefathers’ day, we all knew heavier than air flying machines did not exist, until the Wright Brothers proved otherwise. Jules Verne could extrapolate realistically from known technology to invent his clipper in the clouds, the Albatross. With considerably less realism, HG Wells could extrapolate unrealistically from the fact that a balloon allows man to cross the previously unreachable vertical dimension of space, a time machine would allow man to cross the previously unreachable fourth dimension of time. We allow our imaginations to believe in future things we don’t know, because they are related to present things we do know, some of which, such as the heavier-than-air flying machine, were imaginary in the recent past.

Fantasy has the opposite appeal. It is a genre of the past rather than the future, a past that never existed rather than a future which never will exist (no, Virginia, there will never be faster-than-light drive.) Fantasy casts the illusion of verisimilitude by drawing on the half-remembered and magical things of the former worlds in which our ancestors lived, or by rejecting the crass elements in the mundane world in which we live.

Anything which brushes the magic away, or which intrudes the clamor of the modern world into the echoing music of legend, breaks the spell.

Here, I do not mean any modern element, I mean any modern controversy. When Captain Cully mistakes the magician Schmendrik for Francis Child the collector of Robin Hood ballads, he offers him a taco.

The scene is touching and funny and sad, and no reader notices that Cully was just sitting down to rat soup, because the anachronism is funny, and, more importantly, it does not break the mood. The butterfly who told the Last Unicorn of the Red Bull likewise quotes modern songs and jingles, but the effect is merely to make the world seem timeless and charming, deceptively lighthearted. I say deceptively, because other passages would drew tears from the iron cheek of Pluto. (If you don’t know what book I mean, go leave this blog immediately and read THE LAST UNICORN by Peter S Beagle, and never call yourself a fantasy fan until you have.)

Beagle does not have to describe a unicorn any more than Tolkien has to describe a dragon: we all know what they are. These things live in our imaginations and fantasy takes its verisimilitude from them.

Let me distinguish between old fantasy and new. Fantasy which I read in my youth was written mostly before I was born: Tolkien and Robert E Howard, or the various writers gathered by Lin Carter for the Adult Fantasy imprint of Ballantine Books. Call this Old Fantasy. It rests for the success of its illusion of verisimilitude on the racial memories of the world before science, the world we know from Reformation tales of witchcraft and Renaissance tales of alchemy, and romances of Arthur and epics of the ancient world.

You see, in the days of Old Fantasy, the average schoolboy knew enough to have already present in his imagination images of the noble savages and Indian braves bright with warpaint loping silently through greenwood, or of Arthur’s knights, or Robin Hood’s merry men or the barbaric reavers of Hrolf Kraki. He knew enough myth to recognize the dragons of Beowulf and the Cyclopes of Ulysses, and enough history to recognize the Turkish Harem or the Roman Circus, where Christians were slain by gladiators or vicious beasts, and he knew of the human sacrifices performed by Carthaginians to Baal.

Notice, please, that of all civilizations that have ever existed, no one but the Romans has ever had the institutions of gladiatorial arenas. But this was something that lived in the imagination of schoolboys of the day, so that nearly every fantasy hero is popped into a gladiatorial arena the moment he arrives on Barsoom, assuming he is not first adopted by the noble savages who value battle prowess above all else. The luxurious and over-civilized cities of Conan the Barbarian’s era are Rome or Babylon.

Of old, fantasy was tied much more closely to history. It was practically alternate history, namely, what would the world have been like had actually been true the gods and goblins in which our ancestors believed (or, at least, pretended to believe to patronize their poets) ?

Disgusted with the modern world, authors like Robert E Howard tried their hand at a Homeric epic, or like Tolkien at a medieval Romance in the fashion of Beowulf or the Song of Roland.

Both these authors, the father of Sword-And-Sorcery and the father of High Fantasy, set their mythic realms in periods somewhere in the forgotten past: “between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of.”

Modern schoolboys, for a variety of reasons, none of which bear too close an examination for anyone with a queasy stomach, are far more poorly educated than their fathers, and far more indoctrinated into a particularly parochial and past-hating view, which I hereby dub ‘retrophobia.’

The particular quality of retrophobia is that everything about the past is despised. This includes the remote past, say, AD 50, as well as the near past, say, AD 1950. Some things are despised in a condescending but admiring way, as one might look upon a child, as they are looked upon as the larval forms of enlightenment which will burgeon into the glorious present day, such as the career of Julian the Apostate, and others are despised in a hostile way, as one would look upon an enemy, or a disease which, after long bouts of fever, one has finally thrown aside, such as the witchhunts of the Reformation Era. The sole exception to the first category is that if the advance toward enlightenment was done by Christians for explicitly Christian reasons, it is either to be ignored, such as the abolition of slavery in the Middle Ages, or is to be used as an example of villainy or absurdity, as the Crusades, in which case its fate is to be not only ignored but misrepresented.

Now, logically, one cannot write fantasy for an audience suffering retrophobia. The painted savages of the Sioux and Apache do not exist in the imagination of the retrophobes, only the kindly Indians, now miscalled Native Americans, such as are portrayed in DANCES WITH WOLVES and Disney’s POCAHONTAS. The modern schoolboy has never read a Norse saga, but he may have seen HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON. He has certainly never read any story where a Christian is thrown to the lions by the Romans, but he knows about gladiatorial games from Russell Crowe. Gladiatorial fighting is like a Pokemon match, except with humans!

The second generation of fantasy was not based on history, it was based on Howard and Tolkien and Lovecraft and other authors of the first generation. Those were the images and tropes alive in the imaginations of the audience. Michael Moorcock and Fritz Lieber are still drawing, to some degree, from first generation sources, but Kane of Old Mars is John Carter, and Fafhrd the Barbarian is Conan. Roger Zelanzy inverts the tropes of fantasy in his Amber books by having his main character be a film noir antihero straight out of Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler, and having him thrust into a multiverse-wide Elizabethan revenge drama.

The third generation, I can say very little about, since it was about this time that I lost interest in fantasy, or it lost interest in me. There are occasional exceptions, like THE SORCERER’S HOUSE by Gene Wolfe, or the “Dresden Files” by Jim Butcher, but, for the most part, I cannot slog through something like the “Wheel of Time” series by Robert Jordon or THE DEED OF PAKSENARRION by Elizabeth Moon, and not because there is anything wrong with the writing or even the world building (heaven forbid I criticize authors more skilled than I at my chosen vocation!) but only because the cultural and social assumptions and axioms of their worlds are too close the modern axioms, where the assumption has no reason why it could exist. It breaks the spell of the suspension of disbelief.

I will in all fairness add the caveat that Wheel of Time takes place, like SWORD OF SHANNARA, in a post-apocalyptic world, one where our technology hence our cultural assumptions might have once existed. This means that the author could have, had he thought it necessary to pander to the crabby imagination of conservatives like me, offered some realistic explanation to explain the modernisms inside a pre-modern context. Maybe it was there and I missed it.

In the case of Jordan, the unrealistic detail that broke my suspension of disbelief was that Inns without a nearby cow served milk rather than ale. That did not seem realistic to me, without modern means of transport, refrigeration, or storage.

Again, if memory serves, Elizabeth Moon posits that contraceptive drugs are as readily available as table salt in her medieval co-ed brigade of spearwomen, which at least is a gesture toward explaining away what would otherwise be the insurmountable unrealism of having young mothers on campaigns, waddling pregnant into battle craving pickles and ice cream, or nursing their sucklings one-handed while reloading a crossbow.

While I can imagine societies without gunpowder and without Christianity treating women as equal to men, in the same way that I can imagine Superman’s cousin from the planet Kripton punching evil robots through a wall, nonetheless, I need some sort of explanation to help my imagination along. I at least need an acknowledgment, even if it is only a wink, to tell me the author knows there is a logical discontinuity here. (Yet I fear the modern authors are too poisoned with retrophobia, contempt for reality, or love of theory, to allow themselves to admit there is anything to be explained.)

The smallest figleaf will do, as far as I am concerned. If Xena the Warrior Princess is blessed by the gods to be like Jack Burton and do things no one else can do and see things no one else can see, fine by me. I can now believe she can obliterate a squadron of Spartans, linebackers, and roustabouts. If Buffy the Vampire Slayer has the ghosts of a thousand generations of dead Slayers living in her soul, that is good enough, too. She can break chains with her bare hands. If the Amazon is good with a bow because she had practiced with a bow, that is dandy also, because shooting a man with a bow and arrow is something any woman with a cool nerve, a practiced arm, and a good eye can do.

Myself, I would even believe the Daughter of d’Artagnan in a plumed hat and thigh-high boots could kill a man less skilled in fence than she, because the rapier, which uses the point, is more a matter of hand-eye coordination and speed and less a matter of brute strength than is the saber, which uses the edge. But I would not believe an entire squadron of swordswomen would be as cost-effective to train and maintain as an equal number of athletic young men.

But the Third Wave of Fantasy, as far as I can tell from a distance, do not have imaginations filled with images from real history, as I do, but instead are filled with an earlier generation of fantasy images, Eowyn dressed as Dernhelm riding to her doom, or Red Sonya dressed in a chainmail bikini.

And the imagination is further distorted by the political correctness which makes it a thoughtcrime even to discuss whether or not the word “equality” actually means that jills are just as aggressive, as macho and muscular as jacks, and that girls want to kill bad guys as badly as boys want to get married and give birth.

The question must here arise: It might be realistic to have women back at the camp, out of harm’s way, or reloading the musket rather than firing it, but if you are going to tell a story about elfs riding dragons to the moon, why not just unrealistically have girls built like cheerleaders able to punch out men built like linebackers?

For that matter, why are we talking about realism at all? This is fantasy!

Allow me to quote the father of our beloved genre:

It may sound fantastic to link the term “realism” with Conan; but as a matter of fact – his supernatural adventures aside – he is the most realistic character I ever evolved. He is simply a combination of a number of men I have known, and I think that’s why he seemed to step full-grown into my consciousness when I wrote the first yarn of the series. Some mechanism in my sub-consciousness took the dominant characteristics of various prize-fighters, gunmen, bootleggers, oil field bullies, gamblers, and honest workmen I had come in contact with, and combining them all, produced the amalgamation I call Conan the Cimmerian.

- From a letter to Clark Ashton Smith from Robert E. Howard (23 July 1935)

In other words, fantasy is nothing more than the combination and sublimation of realistic elements, usually realistic elements of the past, into a form found in legends, myths, dreams, symbols, which is familiar to us, despite being unreal.

The question of “why are you talking about realism in a fantasy story?” mistakes the nature of the suspension of disbelief. For the sake of the story, I am willing to believe, for example, that the Force is a mysterious energy field that binds the galaxy together, and that when Obi-Wan Kinobi is chopped to smoking ham cutlets by a plasma-powered lightsaber, Luke the magic farmboy from space can still hear his voice telling him to shoot by faith rather than use his targeting computer. That makes sense to my imagination, poetical sense even if not strict logical sense. But if the sequel says that the Force is produced by microscopic organisms in my bloodstream, even though this makes MORE scientific sense than a mystical energy field, it makes LESS storytelling sense.

I can believe a dragon can fly to the moon with an elf on his back if that is established in the story, and if I am the kind of reader in whose imagination things like elfs and dragons and moons like Dante or Ariosto envisioned, hanging in a breathable aether above the upper clouds, are living things that do not need to be explained, merely invoked.

As far as I am concerned, you can even invoke Brandomart and Camilla and Hyppolita, because these things come from poetic traditions.

But the idea that supermodels built like Twiggy can punch out Joe Lewis and karate chop Bruce Lee and cross lances with Sir Lancelot and cross blades with Alexander the Great, whose whole body (tradition says) is a mass of scars from his many battles, there is nothing in my imagination which corresponds to that. The story teller would have to use at least a modicum of cunning to make the martial maiden come to life and convince me she can wrestle with Hercules.

But there is a second and more powerful objection. Where is the drama, if the princess is as strong or stronger than the prince sent to rescue her?

Which brings me to the second article I read on this topic of late. This was a review of the recent John Carter movie.

http://www.1000misspenthours.com/reviews/reviewsh-m/johncarter.htm

The author begins by making a very good point, one with which I entirely and utterly agree:

Mars is real. That’s been a conundrum for writers of science fiction and fantasy ever since astronomers began to get serious about developing better means of studying the heavens than squinting at them through pairs of little glass lenses. So long as nobody really knew what they’d see from the surface of the Red Planet, Mars offered vast scope for speculation, and what clues to conditions there could be discerned using old-school astronomical techniques certainly were enticing. Mars changes appearance over the course of its orbital cycle, as its axial tilt adjusts the relative angle and intensity of the sunlight striking it. Could those variations in color and topographical distinctness be caused by seasonal changes in vegetation? And what about those uncannily straight “channels” that Giovanni Schiaparelli thought he saw crisscrossing all over the Martian tropics? Mars has polar ice caps, and polar ice caps mean water. Could Schiaparelli’s channels be riverbeds? Or better yet, might they be artificial waterways— not merely channels, but canals? After all, how often does Mother Nature succeed in drawing a straight line? With such mysteries to ponder so close at hand, cosmically speaking, it’s no wonder that Mars would fire the imaginations of authors at every level of intellectual rigor, from Edgar Rice Burroughs to Ray Bradbury to H. G. Wells.

He ends by making a point with which I not only entirely and utterly disagree. Indeed, I find it abominable:

The biggest and most astute improvement, though, concerns the movie’s handling of Dejah Thoris. To be sure, Edgar Rice Burroughs always did better by his heroines than was typical in pulp fiction of his day. By the standards of the 1910’s, his Dejah Thoris is gritty and resourceful, and much more credibly appealing on that score than any mere damsel in distress. Even so, the 21st-century reader notices at once that her primary function is still always to be rescued from some sort of peril, for her laudable efforts to escape or to overcome on her own somehow never quite reach fruition. Andrew Stanton’s Dejah Thoris doesn’t have that problem. Indeed, she might be seen as the fulfillment of the original’s promise. The movie plays up her status as one of Barsoom’s foremost scientists by introducing the princess on the verge of discovering the very same electromagnetic phenomenon that underlies Matai Shang’s death ray. It makes her a fighter of great skill and courage, and drops altogether the stuffy concern for custom and propriety which figures rather too strongly in her personality as presented in the novels. When John Carter hauls out the old “save the heroine from having to marry the villain by busting in on them in mid-ceremony” routine, it earns the cliché by having Dejah Thoris agree to the wedding, if not exactly of her own free will, then at least with a stateswomanlike recognition of what she may gain for her people as a consequence. In short, the film updates Dejah Thoris to preserve, in a modern context, what was always the most radical aspect of Burroughs’s fiction, his notion that a woman becomes worthy of a hero’s affection not by being beautiful or virtuous or well-bred, but by being heroic herself. It’s a shame that John Carter looks poised to become a fiscal disappointment, because I would very much like to see what this team could do with the rest of the saga.

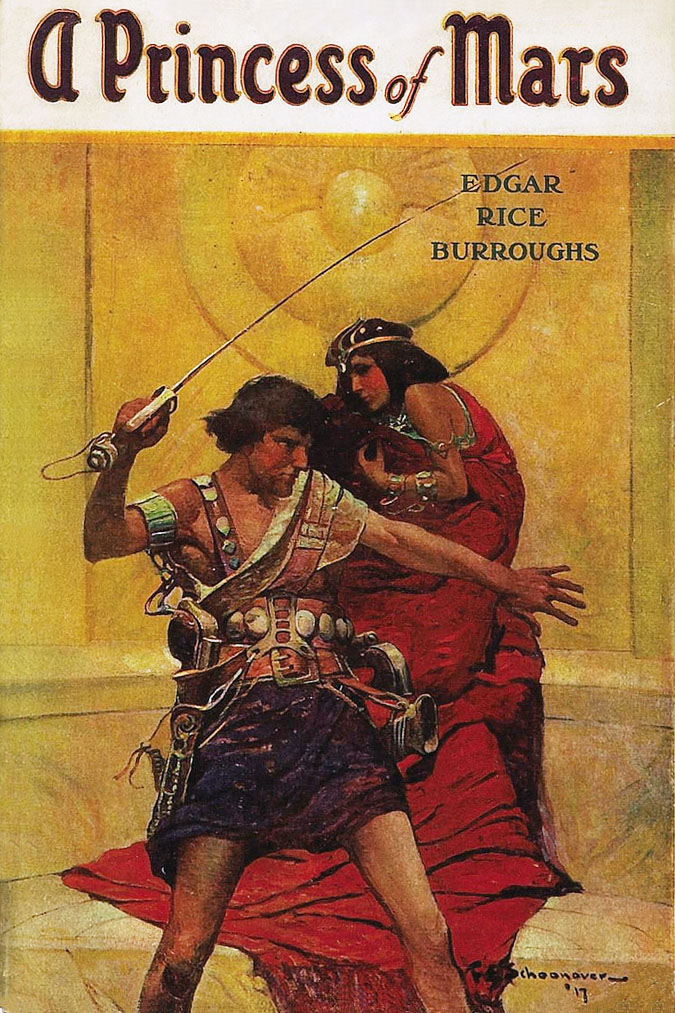

My comment: Dejah Thoris is one of my favorite characters, partly because I came across her at just the right age where that vision of womanhood was ready to appeal to my youthful longings, but partly because of the skill and craft and love used by Edgar Rice Burroughs to envision her.

And I rather doubt this reviewer read the book, or, if he did, he understood it.

For anyone to speak of Dejah Thoris having a “stuffy concern for custom and propriety” is to misunderstand the character, to say the least, or, rather, to come from a culture so degraded that he cannot appreciate what the character stands for. Like Conan the Barbarian, Dejah Thoris is, above all, a vicious and willful savage whose luxurious beauty is flaunted naked to all eyes, adorned with a barbaric wealth of gems, necklaces, ear-rings, finger-rings, anklets, armbands, and so on, and in one hand a jeweled knife. At that same time she is the product of a highly scientific and advanced culture older than Earthly mankind, so advanced that they have forgotten the niceties of compassion, a luxury her dying world cannot afford.

Stuffy? The whole point of the character is that she is not. She is nothing like the prim and proper Earthwomen John Carter left behind in Virginia.

What this reviewer is foolishly mistaking for ‘stuffiness’ is Dejah Thoris’ stern unwillingness to break with the ten-zillion-year-old traditions of her people. That stubbornness is a hallmark both of noble savages and of oriental decadence. It is also one of the plot contrivances which moves Burrough’s romantic plotline along.

In the movie, there were no taboos separating the starcrossed lovers and hence there was no reason for Dejah Thoris not to fornicate with John Carter upon first lust, but also no reason for the lust, since neither character was portrayed as needing, or being attractive to, the other, except as a matter of temporary expedience.

Let me tell you what the character is really like:

Dejah Thoris is the ultimate unattainable woman, not only a princess of a thousand-year-old race still in the first bloom of nubile youth, and naked as a jaybird, but a woman of a planet severed from her true love by impassible interplanetary gulfs. Only on dark Arizona nights can John Carter stare at the sky and see that fleck of ruby-red light, that wandering star of Mars, world of the war god, which holds his true love.

Dejah Thoris was a scientist, or, at least, scientifically trained from the beginning. That is not an invention of the film maker but of the original book. She is shot down and falls among the green Thark horde because she is on a scientific expedition examining the rate of loss of atmosphere that so soon will render Barsoom a dead world.

She was never “gritty” nor “resourceful” but she was brave, as brave as the wife of a Roman or the mother of a Spartan, brave as a Red Indian squaw who falls into the hands of a murderous enemy tribe, and knows that rape and torture await her.

Dejah Thoris gives an impassioned speech to the Thark chieftain, appealing to a better nature which she sees in him and he himself does not, and for a moment of painful hope he is almost swayed. Then she is struck on the face by a brute, but does not complain or show weakness.

This is grit in the sense that Mattie Ross of TRUE GRIT has grit, that is, stoic bravery. But it is stoic bravery from the old romances, from the Indians, from the Romans, from the Spartans. It has nothing to do with modern feminism and everything to do with the harshness and horror of a life of war in a warlike age, yes, even the life of a princess in a warlike age.

As for her need to be rescued, the first thing this reader noticed was that Dejah Thoris needed to be rescued from a political marriage to the prince of a rival city-state, a plot point which the book handled adroitly, with all the melodrama and anxiety the plot of star-crossed love requires, and with perfectly feasible political reality, whereas the movie handled it awkwardly, even stupidly.

The second thing I noticed was that John Carter in the book was a hero and a man and a gentleman and John Carter in the movie was a whiner, once who spends the whole first reel running away from the action, lusting for his gold like Gollum for his ring, or, to use a better example, like Daffy Duck in that cartoon where he and Bugs find Ali Baba’s cave.

In the book, the hero is from the living world of Earth, and remembers such traits and kindness and compassion, and so his advent onto the dying world of Mars, he finds not only his physical strength is greater, but he can both tame vicious Mars-dogs, and win the love and loyalty to Sola and Tars Tarkas, and this helps him escape the deadly peril of the Tharks as much as his astonishing skill with a blade.

If Dejah Thoris needed rescuing from the Green Martians, what of it? So did Kantos Kan. And in a more profound way, Sola, the only woman of the Green Martian race who knew her true parents, also needed rescuing from the Green Martians, or from their dehuminazing custom of communism of offspring. For that matter, John Carter needed rescuing not once but twice. (Once from a gladiatorial circus, see my comment above.)

And Carter rescues everyone on the globe from the danger of asphyxiation in the last chapter of the book.

There are stories where the female is a damsel in distress and nothing more. Miao Yin in BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA is kidnapped by the lords of death in the first reel, and spends the rest of the flick either tied up or hypnotized. I think she speaks one line, maybe only one word. She is the McGuffin.

So, no, I did not notice that Dejah Thoris had no more role in A PRINCESS OF MARS than that of a McGuffin, no character arc, no drama, and made no decisions. I did not notice because it is not true.

It is true that Dejah Thoris is locked in a tower to starve by the malice of the Therns of Mars, along with Thuvia and Phaidor, who perhaps has just stabbed her to death. It is also true that John Carter is imprisoned himself during most of this time.

You can count, if you like, the number of times princesses get kidnapped. It is a world, after all, which practices marriage by abduction, and marrying Dejah Thoris is not only a matter of great political gain, she is also the most beautiful woman of two worlds.

But before your feminist calculator starts leaking smoke, count the times John Carter or one of his friends is kidnapped, enslaved, or imperiled. The numbers are fairly close.

You can also count the times a princess stabs or shoots her abductor, and you will not come away thinking these girls are helpless. It is a warlike world, and everyone goes armed.

Now, all that to one side, what is going on at the root of things is that A PRINCESS OF MARS, along with GODS OF MARS and WARLORD OF MARS forms a notable milestone in the history of fantastic romance and scientific fiction. The story is about an abducted princess and her champion who faces all foes, from rival suitors to implacable customs to vicious beasts to savage hoards to evil plants to sinister cults to buried empires to worldwide asphyxiation, to the abyss of space, to death itself, and he cuts and chops and shoot and slays his way through all opposition, literally from the south pole to the north, to win to the side of the woman he loves.

If you don’t get that, if you don’t sympathize with this, then political correctness has rotted your brain, and you will miss the most important thing there is to know about men and women. We are complimentary and we belong together. We are not like each other. If we were like each other, we would be alone.

I look at this picture and feel a thrill of love and admiration. This is what romance is really all about. The man is willing to die for his lady. To me it seems not only normal, but right.

A modern looks at that same picture and laughs in contempt, or puke in disgust, or rolls his eyes in dismissal. Why should women admire that a man would fight and die to save her? Why should she want to be saved? Why can’t she save herself, have a career, never marry, never have children, and die sterile and alone? Why can’t she be betrayed by one worthless cad after another, or drop any lover who bores her? Why can’t she sleep around and have the Catholic Church pay for her contraception, sterilizations and abortions? Why can’t A be made equal to not-A?

The answer to all this is that human nature is what it is. If sexual differences were a matter of arbitrary cultural conditioning, different cultures would have as many different sexual roles as we have writing systems, alphabets, hieroglyphs, cuneiform, and pictographs, and so on. Instead, in all cultures, the men fight and the women rear the young.

And the other answer is that economics is what it is. What men gain freely, they esteem lightly. If a man does not need to fight a rival, or climb a garden wall, or outwit a chaperon, or even buy a dozen roses, or take a vow to cleave to his bride forsaking all others — if, in other words, dear ladies, you give yourself cheaply to a man and he sheds no blood, no sweat, and no tears, pens no poetry, fights no duels, and spends no sleepless nights, to win you — both he and eventually you will treat the relationship as casual, and you will both hold it, and eventually each other, in contempt.

All women are princesses. Don’t let the modern world tell you otherwise, dear ladies. All women are as remote, if she does not return her suitor’s love, as the distant world which seems but a fugitive red spark in heaven. John Carter fought an entire world, and not just any puny world, but a world of war, and saved it, for his love. Should you ladies demand anything less from your champion?

And all women are lonely. They all need rescuing from that.

If you forget that, you have forgotten the poetry and the tragedy of human nature. The problem with political correctness is not just that it is false, stupid, and satanic, but that it drives all good things in life away, and makes fair things seem foul, and foul things fair.

Unfortunately, I am a fan of the books first and foremost, and I was disappointed and exasperated by this film, and my disappointment and exasperation turned into hatred right at the point where John Carter steps in front of Dejah Thoris with sword drawn to protect her, and, being a modern politically correct unfeminine female, that is to say, dickless he-man with breasts, Dejah Thoris snorts in disbelief, shoves Carter aside, whips out her own sword, and kills a dozen never-to-be-scary-again Thark-shaped balloons.

It was not just stupid, it was an act of deliberate malice aimed at any fans of the original books. Her snort of contempt was the movie maker’s contempt for all fans of romantic adventure.

One would think even the modern writers would realize that in order for a man to be a hero, he has to rescue someone, and in order to be a romantic hero, he has to rescue the damsel, and in order for the damsel to be rescued, she has to be in some situation from which her own strength and wit is insufficient to rescue herself.

Now you may ask: by why should schoolboys dream of riding up on a white horse to rescue a damsel, and why should schoolgirls dream of being rescued by a prince on his charger? Why do bridegrooms carry the bride over the threshold instead of the other way around? Why does Tarzan throw Jane over his shoulder but not Jane throw Tarzan? Why is it normal, and rational and romantic, for a women to want to be swept off her feet?

A full answer would have to discuss such things as economics, and biology, and the Fall of Man, but the short answer is that a man wants to be strong, proud, domineering and masterful, whereas a woman wants to have such a strong man as her very own. Look at what is on the covers of men’s magazines and women’s magazines if you don’t believe me.

Sex by its very nature is complimentary: if men were sexually attracted to the same things women find attractive, it would not be a sexual attraction at all, merely a human friendship. Like it or not, human beings are bipartite creatures, soul and flesh, mind and body. In the same way biologically male and female bodies are attractive each to the other, masculine and feminine personalities are each attractive to the other. Social roles, stories, social signals, distinctive forms of dress and address, all emphasize their differences so that sex is sexier.

In our modern culture, the sexual differences are de-emphasized, woman are pushed to be masculine, men are pushed to be feminine, so among us, sex is trivialized, desecrated, dessicated, and becomes boring, ergo a matter of mutual pornography and mutual exploitation, or, in other words, a matter of mutual loathing rather than mutual joy.

To say any of this cuts against modern political programming, of course, which is based on the envious notion that women must be like men in all ways. Unfortunately, the modern political programming does not allow for romance, heroes, or romantic heroes.

Which is why when a man falls on in a subway track, no one helps him. When a ship runs aground, men shove aside women and children to get to the lifeboats.

Let me add a third link to the two given above, not directly on the topic of egalitarianism in fantasy, but on the topic of retrophobia.

I was reading books reviews on the blog of a man named Michal Wojcik, who, like me, is something of a fan of Lin Carter’s editorial work, a fan of Gene Wolfe, a general bibliophile, and so on.

In a review of several ‘Hollow Earth’ stories, including Bulwer-Lytton’s THE COMING RACE, without turning a hair, as if he does not notice how odd and out-of-place the comment is, the reviewer says this (http://onelastsketch.wordpress.com/2012/04/07/into-the-hollow-earth/):

Yet despite the large output of Hollow Earth-themed scientific romance for a good while, the idea soon dwindled from the book racks. The association with colonial adventure narratives certainly hurts the appeal in our postcolonial times. The close ties with the lost race motif, as well, raises unfortunate connotations.

Allow me to translate from Political Correctness into English. These books will strike the modern reader as racist.

It is not clear if the reviewer means this perception of racism is because modern readers have been programmed to see everything as racist; or whether the reviewer means the writers of times past, taking Darwin’s theory to apply to human beings, thought some races inferior to others, and that this was the cause of European Powers establishing colonies and empires, ergo anything which deals with exotic lands with strange natives and lost races savors of this imperial ambition that is ultimately racist.

I myself think it is stupid to attribute racism to multiracial empires. Imperial ambitions can be found in much more commonplace human motives than a concern for Darwinian race-supremacy, such as, for example, the more obvious motives of fear of rivals, love of honor, and greed for gain.

In any case, the reviewer is a historian, but either he has been cut off by Political Correctness from any sympathy for men of the past, either men who built empires or men who wrote books about Edens or Utopias or savage Wildernesses in unvisited Pellucidar beneath our feet; or our poor reviewer is not cut off from that sympathy, but feels toward it as the author of BEOWULF must have felt about his pagan ancestors. This is, I assume the author feels torn between respect for his ancestors and the knowledge that they were benighted and damned.

Let me hasten to add that I bear no ill will toward Mr Wojcik but instead a great deal of affection. To judge from his words, he and I read the same books and had the same reactions, and both will one day write a hollow earth yarn, so he may be a changeling raised by my true parents or a long lost twin or something. I am not accusing him of anything but being polite, an accusation unlikely (alas) to be leveled against yours truly.

I am accusing the society in which we both live of making such politically correct comments as to sniff with dismissal at a harmless fantasy as a lost race story or a story of vril-powered troglodyte utopia for being racist or colonialist or whatever the thoughtcrime de jour happens to be. Politically insensitive. Not pleasing to our Masters.

Political Correctness damns all past history as being nothing but prologue to the wonderfulness that is us. It also drains the drama and joy out of life, so that a history major cannot read and enjoy a good old fashioned Hollow Earth Lost Race novel without a twinge of conscience, and cannot discuss them without putting up a warning label.

In the final analysis, what is retrophobia? It is not that the moderns hate the past. They hate the truth.

The past, for all its flaws and faults (and let us not romanticize nor underestimate the drawback and even horrors of life in times past) still had cleaner and clearer truths found among them. In this case, the truth about men and women.

And it is to these truth that fantasy, which does indeed romanticize the past (even to an absurd degree), draws the nostalgic reader, the reader who seeks something hard to name, something the modern world does not provide, which, perhaps, no world provides: a haunting sense that truth is shining beyond this world, and we here only see reflections. We only hear the dim echoes of the horns of Elfland blowing, and see among the comets and falling stars some hint of warrior angels streaming behind their shining banners to the combat, fighting wars of which men known nothing.