The Big Three

As a bit of a relief to my readers who are no doubt weary of hearing my Jeremiads and screeds against the evils both political and philosophical which corrupt the modern world, let us turn from the disappointments of today to yesterday’s golden dreams of tomorrow, and talk about the three major science fiction writers of Campbell’s Golden Age.

The Big Three are Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and — wait for it— A.E. van Vogt.

Perhaps you have read books by the first two and never heard of the third. That is sad but not surprising. Perhaps, being a lover of triads, you thought the third Big Name of the Golden Age should be Arthur C. Clarke or Ray Bradbury.

Admired as these authors were and are, no one in the day considered them one of the Big Three. Van Vogt was, for a time, bigger than Asimov and Heinlein in popularity. I have seen articles, including the notoriously unreliable Wikipedia, list one or the other of Clarke and Bradbury as the third of the triad. It is partly to dispel the disturbing tendency toward historical revisionism that I write this article.

For neither of these were Campbell authors, and, indeed, I would argue that Arthur C Clarke is from an older tradition of science fiction than Heinlein and Asimov, and is an heir to H.G. Wells, whereas Bradbury was a man before his time, and fathered a younger tradition. He was “New Wave” a precursor to character-driven SF, years before the New Wave was new. So even if Clarke and Bradbury are cherished men of the Golden Age, they were not of Campbell’s Golden Age. Neither Clarke nor Bradbury wrote in the genre Campbell established.

I cannot speak with any authority about the economic conditions of the time, but I do know that a man could make a living wage in the 1930’s and1940’s just by short story sales if he could sell regularly even to the lower scale magazines, the pulps.

And if he sold a story to the high scale magazines, the slicks, one story could pay his rent and grocery bills for a year. Magazines were the primary source of cheap popular entertainment, more ubiquitous than talkies and more portable than radio. They had a power over the popular imagination unimaginable these days.

Likewise, I cannot say anything about the condition of the genre from my own memory, since this was some twenty years or more before my time, but reading omnivorously as I did of everything in the genre that existed in my youth, any reader could come away with a fairly accurate impression of the state of the genre before and after John W Campbell Jr during his tenure on Astounding Science Fiction later called Analog Science Fiction and Fact.

Indeed, the change of the name itself would give anyone the clue about that change. Aside from a few reprints of literate yet readable speculations from England, the works of H.G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon, and excruciatingly (if not prophetically) accurate technological romances badly translated from the French by Jules Verne, science fiction magazines of the day were mostly boy’s adventure stories set in space, tales actually about mad scientists, yarns of lost races, invasions from the Earth’s core, and various forms of Apocalypse. It was an age of Space Opera, of the Galactic Patrol of E.E. “Doc” Smith and of the Legion of Time of Jack Williamson. It was the time of C.L. Moore and Leigh Brackett and “World-Wrecker” Hamilton (a nickname oft I envy). It was the time of wonder and astonishment and weird tales, and the magazine devoted to such beloved juvenilia had names like WONDER and ASTONISHMENT and WEIRD TALES.

Campbell established a new type of story, less about weirdness and wonder and more about what we now call “Hard” Science Fiction, which consists of two elements. Both elements had been present in the prior lineage of the genre: first, a social or philosophical commentary about man’s place in the universe, as we might see in H.G. Wells; and, second, a fascination with the nuts and bolts of legitimate speculation into the near future of technical advance, as we might see in Jules Verne.

Before Campbell, these two had not been combined. Campbell’s genius was to wed them: Hard SF is social or philosophical commentary about the changes to man’s place in the universe brought about by near future technical advances.

The social commentary we see in the dismal tales of H.G. Wells is utopian and negative. Do not be surprised if I call them dismal, but reread them for yourself, and decide whether any of them has a happy outlook or happy ending.

Nor be surprised if I say Utopianism is negative, because it is little more than revulsion toward the unhappy circumstances of the present day, combined with dreams, sometimes noble but more often naïve and ridiculous, about how progress will improve the human condition.

Reading Mr. Wells’ socialist sentiments these days, now that socialism has murdered, in the Twentieth Century, some 262,000,000 people (enough that if the corpses were laid head to toe, the line of death would circle the earth ten times) is indeed a disquieting experience. It is akin to reading a letter penned by a fourteen-year-old girl, filled with charming, goofy, unrealistic and faintly disquieting hopes, about some get-rich-quick scheme or idealistic cult she means to join, whose handsome leader she was to wed, boasting how it would aid her impoverished mother and win her fame; but you are reading this letter while sitting in some autumnal dusk on her neglected gravestone where have been buried, years and years after the letter in your hand was written, the few parts of her body, recovered from the kitchen behind the cult’s brothel, such as a severed arm bruised with manacles and covered with needle tracks and gnaw marks. And no wedding ring was on the finger. That is what reading the deluded predictions of socialist utopia from before the age of world wars is akin.

Campbell embodied the American spirit of optimist just as Wells embodied the European spirit of pessimism. The social philosophy, even among Big Three and the other writers in his stable, had a certain common element. It is difficult to define for a modern reader, since the ideas were an extension of the scientific optimism and classical liberalism of the time.

The modern Radical would see them as conservative, since they placed faith in the free market, individual initiative and ingenuity, and the various values and standards common to civilized men which modern Radical have set about to undermine and destroy. But the modern Conservative would see a Radical bent to such tales, since they place faith in the malleability of human nature, had faith in the progress and improvement of man, the omnipotence of big governments carrying out big programs. Theses stories dismiss tradition as mere pigheadedness. These stories show a touching childlike faith in Theory, and, for conservatives (in the brilliant words of William Briggs) “Love of Theory is the Root of All Evil.”

I suggest that the modern prism of seeing all things as either Radical or Conservative is misleading here, especially since we live in an age when the so-called Conservatives seek radial changes to our dying socialist systems and so-called Radical are reactionary conformists seeking above all things to keep in place programs and policies dating from the days before the invention of the jet engine or the color television.

These stories were Hard SF. They were Campbelline, and come from a time and reflect an optimism which only conservatives foretelling radical changes could reflect.

Now, I have made two outrageous claims here: first, that the Big Three had even a slightly conservative outlook on anything. That certainly does not seem to be the case, since the Big Three were a Jewish Liberal, a Rock-Ribbed Libertarian, and Scientologist.

The second outrageous claim is that Hard SF is not Hard SF.

Let me defend the second outrageous claim, if it can be defended, first.

Usually when the Linnaeus society, bored with long afternoons of debating the taxonomy of various species of beetle, wants to get drunk and discuss the definitions and boundary lines of the various genres and subgenres of science fiction and fantasy, the common consensus is that “Hard SF” is any story whose core revolves around some real science, usually astronomy and that “Soft SF” is any story whose core revolves around the humanities or some less rigorous discipline.

The short story NEUTRON STAR by Larry Niven is a perfect example of Hard SF, since the tale cannot be understood, nor even told, without an understanding the tidal effects of gravitating bodies. The novel LANGUAGES OF PAO by Jack Vance is a perfect example of Soft SF, since the tale cannot be understood, nor even told, without an understanding of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis that language influences psychology.

I suggest that the Linnaeus society is wrongly gathering too many stories into the Hard SF category, because it is only looking at the one element of world-building.

I have to digress to explain that comment: In addition to the elements common to all genres, such as plot, theme, characters, and setting, science fiction and fantasy have one element no other genre (except possibly horror) has or can have: world building.

The science fiction story not only takes place in a futuristic or extraterrestrial setting, it takes place with the understanding that the rules of what can and cannot happen are different from the rules here and now on Earth, here in the fields we know. Indeed, many a Twilight Zone or near-future fiction is science fiction even though the setting is neither futuristic nor extraterrestrial, simply because something in the here and now, something in an otherwise ordinary setting, which breaks the rules we know, such as the mysterious children from ROSWELL, or their parents from the People Stories of Zenna Henderson, or Professor Pinero’s machine which predicts how long a man will live.

Whether a story is “Hard SF” or “Soft SF” according to the common Linnaean taxonomy only tells you about the World-Building element. I submit to you, my readers, that this is insufficient, since taxonomy should also tell something of the descent of the organism, or, in this case, the grouping of certain tales and novels into sub-genres should also tell you something of the other elements of the story, including the plot, character, and theme.

If you like, we can call this sub-genre “Campbellian Hard SF” with the understanding that when SF stories moved into novels and other media in the 1950’s and later, the other families of “Hard SF” all descended from this original ancestor. I suggest here that Campbellian Hard SF had a common type of plot, characterization, and theme, in addition to the hardness of its worldbuilding, which gave it its defining quality.

Let us stroll, or, rather, sprint down memory lane, by mentioning three or four of the famous tales of the Big Three that made them famous. If you are not familiar with this stories, you young whippersnapper, go get some anthology of stories back in the days when the moonrocket, instead of being a nostalgic memory of the old, was a pipe dream of the young.

A.E. VAN VOGT:

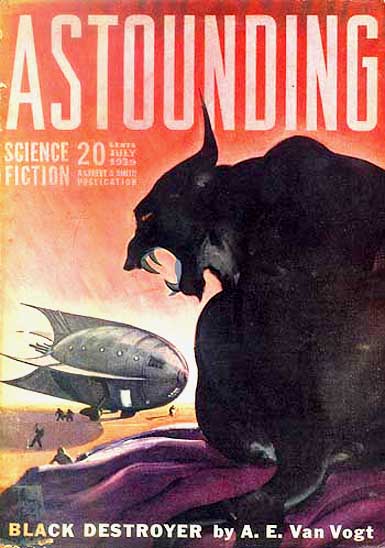

The first story that started the Golden Age was ‘The Black Destroyer’ by A.E. van Vogt. The story concerns an interstellar expedition landing on a ruined and seemingly empty world, and bringing aboard their ship what they deem to be a beast, but which in fact is the highly intelligent and morally degenerate savage last survivor of the once-great civilization whose towers are rotting around them. The monster is not able to contain its fundamentally emotional nature, nor to adapt to the new situation, despite the superhuman control it possesses over energies and elements in its environment. Korita, the historian, is able to recognize the psychological limitations of the monster based on a Spenglarian view of cycles of history, and this enables the humans to prevail.

The tale contained in embryo the elements of the typical Van Vogt tale: superhuman powers, in this case housed in the ruthless and monstrous form of the Couerl, the interest in psychology and parapsychology, the scope of action, and the breathless pacing which was Van Vogt’s trademark, including sudden scene shifts and scenes from the monster’s point of view.

SLAN followed after several stories of superhuman monsters similar to ‘The Black Destroyer’ but in this case Van Vogt rose to the challenge (which Campbell offered to more than one in his stable) of writing a story about a superhuman being that a human audience could read.

Cleverly, Van Vogt did this by making the star of his tale a child superhuman, who in his youth is not yet beyond human comprehension. Like a Tarzan raised by apes, Jommy Cross is a Slan, a superhuman, raised by men. To make the boy an orphan not likely to be returned to his parents, Van Vogt invented a world where the humans have committed genocide on the superior beings, and hate them and hunt them down. Unusually for a science fiction story, SLAN recounts not merely Jommy Cross’ escape from his deadly foes, but unfolds the mystery which surrounds the origin and secret history of the Slans, making it a rare story indeed: a detective story about the life and death and destiny of two and three whole intelligent races. What makes the resolution doubly rare is that the problem is solved, not conquered. That is, intellect rather than courage ends the book. Instead of a set piece fight scene as one would expect in a space opera, we have instead an almost mystical revelation of man’s place in the scheme of evolution and cosmic progress.

Any man living in December of 1940, could see the echoes of the evolutionary supremacy theories behind the European War, and compare the superior beings of the Slans, whose moral fineness is as high as their intelligence is broad, with the loutish brutes of Germany and Italy and Russia swimming through their bloodstained headlines of the time. Also, the average SF fan regarded himself as a bit of a visionary or embryonic superhuman, for being able to imagine a future the dullards and conformists of the greater world could not, and likened his imaginary persecution of his imaginary superiority to that of the slans. It was a book that lodged in the heart of the spirit of the times in the fandom of the times.

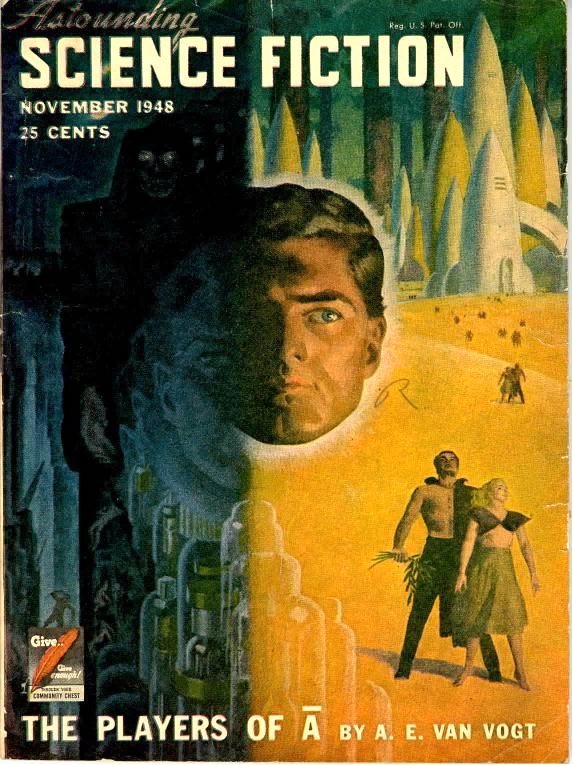

WORLD OF NULL-A was Van Vogt’s next serialized novel, and, I regret to say, marks the peak of his career. Few, or none, of his later books achieved the level of ingenuity, story-telling skill, nor popularity as this. Once again, the tale is about a superhuman being, and once again the challenge is how to make such a character sympathetic to the human readers, which in this case is done by making the superhuman an amnesiac.

The tale concerns one Gilbert Gosseyn, a widower who presents himself in the City of the Machine for the great Games which establish any man’s role in the political and business leadership of the world. The Games in this case are not gladiatorial combats, but psychological assessments of a non-Aristotelian philosophy of neurolinguistics called General Semantics. The conceit of the story is that the psychological knowledge of the future has advanced to such a degree that psychosis, neurosis, and their resulting criminal and selfish behaviors can be trained out of the human nervous system. Gosseyn discovers during a routine security scan of his nervous system by a highly advanced thinking machine (ironically called simply a ‘lie detector’) that he is not who he thinks he is; when agents of a gang that have corrupted the game start gunning for him, he finds he is not what he thinks he is. To solve the mystery of himself is the central plot of the book, if not the Riddle of the Sphinx.

I will add mention of the ‘Weapon Shops’ stories, including the novel WEAPON MAKERS OF ISHER. The conceit of these tales is that men, for better or worse, get the type of government they deserve, which means that immoral men cannot be preserved from selling themselves into a tyranny. The only moral way—since man cannot forced to be free—to preserve their liberty is to ensure that men have the opportunity to buy weapons for self-defense so that no government might ever take that final step of giving man a government worse than he deserves, but then has no power to change.

For such a reason and this limited reason only the Weapon Shops, defended by all the instruments of unthinkably futuristic science, stand ready to sell energy firearms to the common man. The stories themselves are tales of time paradox and retribution against corrupt corporations and institutions of interplanetary Isher Empire. The dangers of private firearm ownership are magically waved away, since the guns sold by the Weapon Shops are somehow programmed not to fire except in legitimate self-defense. Nonetheless, the phrase ‘The Right to Buy Weapons is the Right to be Free’ which was utterly unremarkable when the stories were written in the 1940’s, in these far darker (and far more foolish) modern days offends many an authoritarian ear, or sound like the lift of golden trumpets those who recall liberty.

ISAAC ASIMOV:

Asimov’s most famous three inventions were not his novels, which were clever, but his short stories.

‘Nightfall’ may be one of the most famous short stories of science fiction, so I feel no remorse in exposing its surprise ending. It was intended as a philosophical rebuke to the sentiment of Emerson that if the stars only rose once in a thousand years, men would glorify God in awe. Campbell drily suggested that instead they would go mad, and Asimov invented a plausible reason for nightfall to happen so rarely: namely, that the dwellers in a multiple star system, surrounded by suns on every side, would only experience night once every thousand years when all the suns were in conjunction.

The tale is is cleverly-constructed as a detective story (dropping and resolving clues is Asimov’s strong point) when three scientists (as forgettable as they are lacking in personality–characterization is not Asimov’s strong point) attempt to discover why there are ruins in the geologic strata, spaced evenly once per millennium, or why all men are afraid of the dark, a condition that never naturally arises on this world. Having never developed any artificial lights, when night falls, the population goes insane, and burns their cities and their civilization to create a few hours of light.

His positronic robot stories are all set up as detective stories, the solution of which is based on some unexpected application of the ‘Three Laws of Robots’. The fame of these stories is difficult to understand except when viewed against the background of their time. Until then, robots were always Frankenstein’s monsters, as in Rossum’s Universal Robots, or something of the sort which rose up and destroyed its creator; or else they were the Tin Woodman, a human in all but his construction materials, as in Helen O’Loy by Lester del Ray or Jay Score Eric Frank Russell. The philosophical conceit behind the Asimov robot stories was simple but brilliant: Asimov assumed that robots were neither monsters nor men of iron, but instead were tools, intelligent tools, but tools nonetheless, who could not and did not act other than as designed.

The final set of science fiction stories on which his fame rests are his ‘Foundation’ stories, later gathered into a chronological anthology to pass as novels. It was Gibbons’ Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire set in space. The grandeur of the setting and the conceit was sufficient to carry the meandering series through one trilogy and perhaps another: the idea was that humans have free will only as individuals, whereas in statistically large enough groups, countless worlds upon worlds, their actions are predictable in much the same way that the Gas Laws predict the behavior of gas particles in the aggregate, never as individuals. To forestall the decline and fall of the Galactic Empire, or to shorten the period of its Dark Ages, Hari Seldon, armed with the predictive science of history which he alone invents, sets in motion a few small events, such as the establishment of an encyclopedia foundation, in exactly the area and under the circumstances needed to see to the preservation of science and the rise of the Second Empire.

We never discover if the author had the Carolingian Empire of the Franks in mind, or perhaps the Holy Roman Empire of central German, or the Tsar of the Russias, or the British Empire as his model for the Second Empire, because the series falls short of its promised culmination by some centuries.

ROBERT HEINLEIN:

Robert Heinlein is a special case, because, unlike the others of the Big Three, he actually became bigger after he left Campbell’s circle and was no longer one of the Three. His fame mainly rests with his charming and well written Juveniles, the last of which, STARSHIP TROOPERS, made the rather unexceptional argument that nations who cannot produce soldiers willing to die in the common defense perish of terminal selfishness.

Unfortunately, this was written during a generation, the Baby Boomers, suffering from a terminal case of selfishness, and many of their more unsightly ilk threw temper tantrums at this display of plain common sense on Heinlein’s part, and so they called him bad names. (Not being very imaginative, the only bad names Baby Boomers can think of are “Racist” and “Sexist” and “Fascist” and then in the late 1970’s, when sodomy became fashionable, they called him a “Homophobe” a noise-word which they invented whose meaning evaporates on close inspection.)

His larger claim to fame was STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND, which is a paean to terminal selfishness, yea, even unto claiming divinity for one’s own awesome self (one presumes for folks who own no looking glasses). This satire mocked monogamy and monotheism, and so many a Baby Boomer was mollified and amused.

His best work was oddly his least controversial, MOON IS A HARSH MISTRESS, which retold the America Revolution of 1776 set in space, and stars perhaps his only truly loveable character, a computer named Mike.

The only controversial element of the tale was the praise of polyandrous polygamy, which no doubt sounded much more realistic and turned fewer stomachs to a generation of readers who lived in a fairly decent moral atmosphere, in a green land where the human wreckage of the sexual revolution waited undreamed and unimagined in their future: the skull-pyramids of abortions, the countless bastard children and fatherless children and husbandless mothers and teenaged mothers, and a worldview so lacking in hope that the majority of the a population self-medicates itself into numbness to stave off despair. Yes, no doubt the speculation seemed more realistic in those gullible days, among those most gullible generation of all time, that a life of orgy was good for raising kids.

But it is his short stories and serialized novels which won him fame to the readers of Astounding and Analog, and here it was his ‘Future History’ stories that captured the imagination of the readership.

These stories established a consensus of what the near future was supposed to look like. Private enterprise, in the spirit of the Wright Brothers or Sikorsky, would develop rocketry. Pioneers would first explore, then colonize Luna, Mars, Venus, and the moons of Jupiter. The difficulties and dangers would be met and overcome by much perseverance, much hard work, much engineering know-how, and a little luck. There would be setbacks due to the forces of unreason, and in Heinlein’s world this meant the ‘Crazy Years’ or the rise of religious theocratic fascism by the year 2012. Advances in medicine would produce longevity, progress in liberty would abolish all traditional moral norms except a touchy personal honor and a gentlemanly largesse to guests, and General Semantics (an idea he borrows from Van Vogt) would lead to the maturity of man, and a Covenant forbidding only acts of fraud and aggression. Then Man would be fully mature, faster than light drive would be invented, and a new frontier would open among the stars. Man would pioneer forever.

The three key stories in his Future History are ‘Requiem’, which concerns a man too old for space travel hiring one last rocket to the Moon, which, as it turns out, his genius opened for colonization, but the strain of take-off and landing kills him, and so he is buried in the airless dust of his beloved Luna; ‘Green Hills of Earth’ which concerns the astonishing personal bravery of an aging and blind poet, who, during an emergency, mans his post in a radiation-flooded engine room to ensure the safety of his shipmates, and he dies singing of an Earth he will never see again; and ‘Logic of Empire’ and remarkably unsympathetic examination of the economics behind indentured servitude and other cruel practices needed for colonization. These stories are key because they emphasize the sacrifices needed for the interplanetary future to be made real.

In those days, before the Welfare state drained both the money and the talent needed for such a venture, and Nihilism bred the pioneer spirit out of men, and then the manhood, the colonization of space was a perfectly reasonable dream.

Contemplate the works of these Big Three in this short summation. I submit to your candid judgment that there is more in common in these stories than merely the world-building conception of “Hard SF.”

Indeed, most of these stories are not very “Hard” at all. The Van Vogt stories are replete with unscientific gobbledygook as mindreading guns, time travel, teleportation, and the transfer of human memory from clone to clone. Asimov’s planet without a night as well as his Galactic Empire whose history can be predicted by statistics do not bear very close investigation, and even the theory of intelligent robots whose brains can only think what they are told to think evaporates upon sober reflection.

Contemplate, despite the disparity of setting and authors, the unity of characters, theme and philosophy. This was Campbell’s philosophy. It was the worldview, or, rather, since it was not defined and articulated, the mood he and his writers put across.

First, the prime philosophical assumption in all these tales was that mankind is malleable, and therefore that technical changes, and, more importantly, advances in psychology and anthropology, could lead to glorious breakthroughs in the human condition, an evolution upward. The malleability of man is the whole point of Asimov’s nihilistic ‘Nightfall’ and the need for moral codes to bend like the Lesbian Rule to the cold needs of the circumstances is the point of Heinlein’s cynical ‘Logic of Empire.’ The inability to adapt was on display in Van Vogt’s ‘The Black Destroyer’ and the ultimate triumph of malleability, which is the adaption to the next highest plane of existence above man, as far as man is above apes, the region of the superman, is the prime theme of Van Vogt’s SLAN and WORLD OF NULL-A.

As a side-note, it must be observed that Van Vogt held memory to be identity—that a man was only what he consciously and subconsciously recalled himself to be, and that this forms the main point of WORLD OF NULL-A and its sequel PAWNS OF NULL-A (also called PLAYERS OF NULL-A). But if identity is memory, and memory can be molded, so too can Man.

Second, the characters are remarkably similar men. All these protagonists triumph, when they triumph, through their intellect and their correctly set moral compass. They are not action heroes like the Gray Lensman or Northwest Smith, nor are they mere passive observers like the Time Traveler of H.G. Wells, or the forgotten viewpoint characters who observed the Martian invasion or the death of Dr. Moreau. They are men who solve problems, from how to stop a tunnel leak on the Moon to how to stop the downfall of a Galactic Empire to how to solve the riddle of life and identity and immortality.

The point of Asimov Robot stories, for example, which may be hard for a modern reader to understand, was that robots were neither Frankenstein monsters nor humans made of metal. They were tools which, when they malfunctioned, could be fixed. All these stories are about fixing problems, which a Frankenstein monster story cannot be. In the background of all the Robot Stories and all the Foundation stories is the ideal of man as problem solver.

Finally, the theme was an optimistic one, which said that men were moral creatures who were, or could become, large enough in their time to conquer the stars.

Asimov, who was a Liberal, had no understanding of what morality was or what it was for, so it never appears in his stories, but he clearly thought it was man’s duty to think clearly and to abide by what his reason taught him. Only the cleverness of science would save the Galactic Empire from eternal darkness.

In Heinlein, morality was always voluntary and always based on a firm sense of personal honor and duty. Honor what keeps a blind poet at his duty station even unto death.

Heinlein’s sexual neuroses, thankfully absent from his juveniles and Future History stories might seem to be at odds with this sense of honor, but the libertarian conceit in his philosophy pretended that such vices could be indulged without harm if done by sufficiently mature and virtuous men. Given this false-to-facts conceit, it becomes at least self-consistent for a man to preach that personal independence both required patriotic defense of self and home and laws and race, and permitted any vice or self-indulgence as the self-sovereign individual or self-apotheosized god might please himself to do.

A.E. van Vogt, the least well remembered of the three, rejected, and rightly so, the shallow philosophical concepts of the European intellectuals as to what would constitute the superman, the next evolutionary step beyond man. The Europeans assumed the next stage of morality was to shed all moral scruples, and to become as cold and hard as a machine.

Do not be deceived, O reader, by such external and extraneous frippery as the mind reading tendrils of Jommy Cross, or the teleportation of Gilbert Gosseyn, or the immortality of Walter S. DeLany, founder of the Weapon Shops. These superman were superior, precisely because their moral conscience and altruism of the supermen was superior. The superpowered Coeurl and the Rull and other monsters from his early stories were inferior because of their inflexibility, their moral retardation. For Van Vogt, the larger brain of the Martians of H.G. Wells, or the cold remorselessness of the superman imagined by Nietzsche were of no account if not also wedded to a greater moral sense.

The philosophy of all three, and indeed of Campbell himself, as we can see in the types of stories he wrote and bought, agreed on its prime axiom: Man is the measure of all things, and if he measures himself against the infinite hostility of the infinite cosmos, he must grow in his soul and reason, and be large enough to encompass that cosmos.

This was not Arthur C Clarke’s view, which was more similar to H.G. Wells’ view, that man would eventually evolve into something glorious in its own way but ultimately inhuman, and certainly not Ray Bradbury’s view, which was not so impressed with vast vistas and boastful futures, and more interested in the joys of home and hearth and the mysteries of the woods beyond the backyard, and the deeper mysteries of the human heart.

In the Hard SF view Campbell spread, we men are Homo Instrumenta, the Tool-Using Man, the Problem-Solving Man. Behind us is the ape-man and before us is the interstellar man, the cosmic man.

This is perhaps the inevitable outgrowth of the Enlightenment philosophy which informs the American character. These are typical or even archetypical American stories, as much as anything by Mark Twain or Ambrose Bierce.

The cynicism met in the stories is similar to the unromantic view of man, ambitious, easily tempted man, which underpins so much of the American character. It is why we mistrust Big Business and Big Government and credentialed yammerheads without a lick of common sense.

But the optimism, the belief that a clever man with the clever system can solve things, fix things, correct things, also underpins so much of the American character. That is why we trust the brain trusts and experts from City Hall and concerned activists from the college campuses to organize and solve public matters, and why we trust free enterprise.

If any man can explain why Americans mistrust Big Business and trust Free Enterprise, trust academicians and mistrust yammerheads, trust City Hall and mistrust Big Government, that man can explain the American character.

And that man, furthermore, will understand that “Hard SF” is not just any story that puts technology at its heart. The heart of Hard SF is this cynical optimism, the paradox of men whose feet are firmly planted on the ground, and yet whose hands reach for the stars.