DR STRANGE

The film is probably no longer in theaters, but I finally have time to write a belated review of this film.

Short Review:

Spectacular, magical, enchanting, overawing, satisfying! Five stars out of five.

Medium-Sized Review:

I went in with very, very low expectations, and so was shocked with the pleasant surprise of everything being better than expected. You, dear reader, reading these words where I shall overpraise the movie will no doubt have expectations set too high, and hence may be disappointed. Such is the way of the world.

I confess I was prepared to hate this film. I am a devout fanboy of the original property from way back, so when ads for the film showed changes to the source material, including transforming the Ancient One from an old Tibetan man to a bald Scottish girl, or changing the middle-European Baron Mordo to an impressive looking black guy, I feared these were political correctness edits made to propitiate the dark powers Leftist worship, and that the flick would stink like a barrel of stale and rotting fish.

I was pleasantly surprised. The visuals were spectacular and evoked the proper mood of mystic menace; the storyline was tight, thrilling, funny, true enough to the origin to please purists while clear enough to please newcomers; the acting was top notch; the difficult task of making a magician seem mysterious without being too dark was negotiated, as was the subtler difficult of magic the limits of magic clear enough to retain the drama of the conflict.

All in all, an excellent entry into the Marvel film canon.

Long Review:

The long review will be, alas, very long indeed, because in order to tell you what I liked about the film, I want to tell you what I like about Dr Strange, the nostalgic pleasure of the comic book for me, but then also tell the reader (if patience lasts so long) and about stories where the magician is the hero in general. I regard such stories as singularly difficult to tell well, as so when I see it done well (as I did in this film) I wish to explain myself thoroughly.

So let me divide this column into three parts: a look at the comic, a reflection of why magicians are hard to portray as heroes, and a review of the film. Readers interest only in the third part can skim or skip the first two.

THE SOURCE MATERIAL

Not only am I a huge fan of the comic book from which this character comes, his comic was the first I ever read and indeed is the reason why I read comics at all.

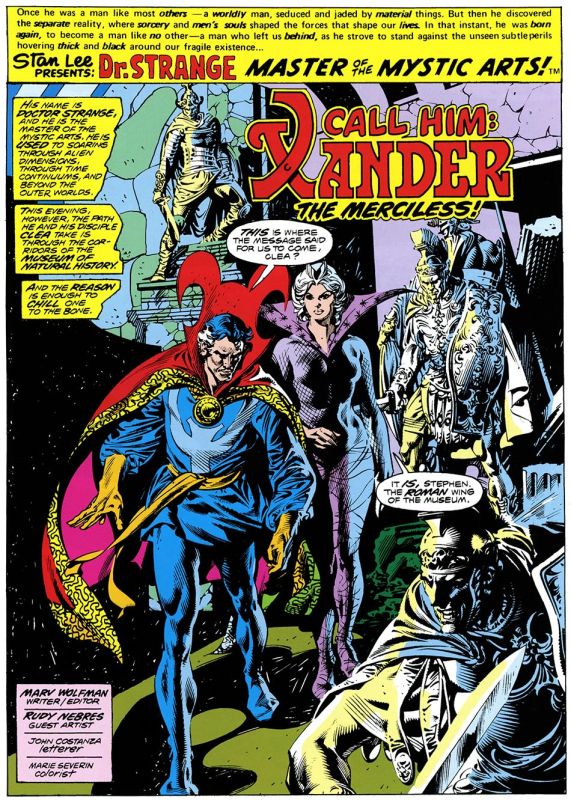

To this day, I remember the number (#20) the artwork of the issue (the magnificent Rudy Nebres did the pencils and inks) and the plotline (Xander the Merciless, a servant of the Creators, who were living stars that could obtain the shapes of men, attacked the good doctor as part of a plan to seize control of the Wheel of Fate, and rewrite the nature of reality). Thanks to the miracle of the Internet, I can present the very page to you:

There were many good runs of this book, and two or three simply spectacular ones. My favorite include the original Stan Lee/Steve Ditko team up in Strange Tales 110-146 (particularly starting with 130) the Robert E Howard flavored stories from Marvel Premier 03-14, the Silver Dagger stories Doctor Strange vol 2 from 01-06, and the chronicle of the Creators from 17-28.

Comics back in the day were not designed to be opaque to newcomers, as, alas, one too many modern comic book tends to be. Hence, the sharp eyed reader can spot the two sentence summation on the opening page of the character and his background. Allow me to quote:

Once he was a man like most others — a worldly man, seduced and jaded by material things. But then he discovered a separate reality, where sorcery and men’s souls shaped the forces that shape our lives. In that instant, he was born again, to become a man like no other — a man who left us behind, as he strove to stand against the unseen subtle perils hovering thick and black around our fragile existence … DR. STRANGE. MASTER OF THE MYSTIC ARTS!

This introductory quote sums up the essential few elements that a weird tale of eldritch imagination and supernatural adventure is supposed to capture: first, that mundane and material reality is both false and fragile; false because there is a separate and higher reality, and fragile because the magic powers that walk the night world are overwhelmingly more potent that limited mortal men can fend off.

The second element is of the enlightened man, the sage, the mage, the magician, the man of mystery, who, in this case, is not a menace nor a mentor but the hero himself, who battles the unseen.

He fights the invisible and overpowering forces, beyond the eyesight of the benighted man, that walk among us, unseen, or press against the fragile veil, thin as glass, which is all that fences us from the dark dimensions.

MAGICIAN AS HERO

There is a balance which must be struck in any story where the hero is a magician.

The magic in a story like this is not the fairy magic which brings colors to the flowers in spring or makes babies laugh or Tinkerbell fly. It is meant to be black magic. Not just overly cautious Christians but all in the audience are supposed to see the magical arts as occult, that is, hidden, because it is dark. Magic is of the realm of things Man was Not Meant to Know.

It is similar to the balance struck when a vigilante is made the hero, a man outside the law.

Consider this: The Shadow, hero of radio plays, pulps and comics, movies and serials, has all the trappings of a villain. He dressed is a black cap and black hat, has a laugh as sinister as that of a mad scientist, and, in the radio version, can cloud men’s minds with mystic powers he learned in the Far East. He is a master of disguise, and, like the Batman who follows in his footsteps, he seeks to terrify cowardly and superstitious crooks with his dark, theatrical menace.

So how is he a good guy?

He is a good guy because all his dark powers are bent against gangland crooks and spies and the like, and he protects the innocent.

In other words, the vigilante hero who dresses in black has to retain the dark and wicked glamour of the devils, but fight on the side of the angels.

Likewise with a magician as a hero.

In fairy tales, the witch or warlock is either the villain or the wise sage. While duels between wizards are common enough in modern post Gary Gygax literature, in older stories, the wizard was usually the one who establishes the obstacle in the plot the protagonists over come: the wizard is the one who places the princess in an enchanted sleep, or turns the prince into a frog, and the plot is the struggle to break the enchanter’s evil spell.

Magicians are rightly regarded as villainous for the same reason a poisoner is regarded as less honorable than a duelist. The magician cheats: he operates by stealth, consulting with ghosts or wrapped in a cloak of invisibility. A witch disguises herself as a poor old peddler woman and poisons cute girls with an apple. An enchantress clouds the wits. A siren lures sailors to death on the rocks and reefs. A magician is someone who knows the cheat codes of the universe.

By the same token, the wizard as a wise sage in older stories acts like Merlin the Magician in Round Table stories: he is there as a supporting character, not the main actor. Rarely if ever does he overcome the back knight by fuddling him with a sleeping potion. The magician’s job is to tell King Arthur where to find Excalibur. The magician as sage is like Hermes in the Odyssey. He gives to Odysseus a magic herb to immunize him from the wicked wiles of Circe, but Hermes does not overcome her, Odysseus does.

But making the hero a magician entails an entirely different perspective, even though certain elements from the older stories have to be preserved.

The element of the occult must be preserved, that is, the hero magician is one who has had a spiritual awakening, and stepped outside of our mundane world and into the larger world beyond. The large point is that the magician is hidden, and cannot return to his old life, save as a strange visitor.

The magician’s awakening is meant to remind the audience of any enlightenment, baptism, or initiation where our old world is left behind and grows small. The point here is that the larger world is secret, not meant for the eyes of the unenlightened.

The second element is the power fantasy. Our hero must be able to do the things we idly wish we could do. Flight, invisibility, mesmerism and command over nature are all commonplace powers in tales of this type, because these are concrete metaphors for the desire to escape the limitations of human nature, but instead to be like a spirit.

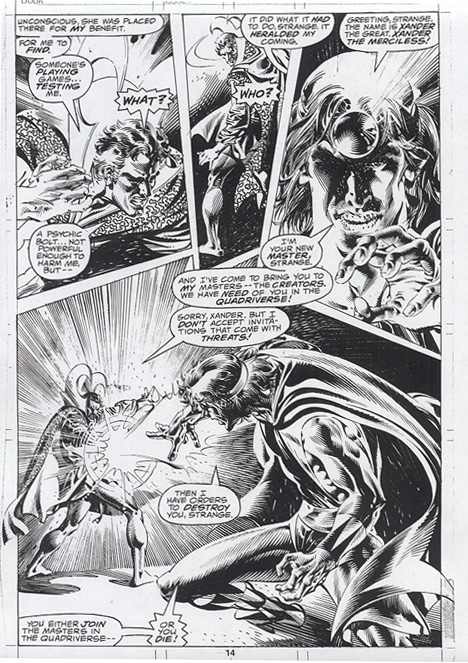

Which powers? In a story directed toward girls, the cute little witch often exercises command over nature in the fashion of a Disney princess, by having beasts and birds befriend and fawn on her. In a story for boys, it is earthquakes and thunderstorms nature is asked to provide. Even in the comic book version of Dr Strange note that our magicians are throwing lightning bolts, the weapon of Jove, at each other, or some ectoplasmic energy even more unusual.

But this brings up the fundamental problem with warlock-protagonists which all authors attempting such tales must face: on the one hand, the magician has to have some magical powers, or else the story is not a weird tale. On the other hand, the audience has to be told or shown early on in any such tale what the magician’s magic CANNOT do.

If the sorceress is tied to the railroad tracks, but the reader has not been told heretofore that she has the power to turn ropes into daisy chains, freeze moving objects, and she can also teleport, turn insubstantial, travel in time, or turn into a twinkle of light at will, then the scene is utterly without tension hence without drama.

But if the selfsame sorceress is established in the opening to have the limit that she has to speak the magic word Abracadabra to access her magic powers, or must have her wand in her hand, or if her charms only work during the day, or if she has only powers over water but cannot influence iron, then tying her to the railroad track can be quite dramatic: for then we can watch with bated breath while she tries to work the gag loose even as the train is bearing down on her, or reaching with her bound hands to where a friendly bird is trying to nudge her wand toward her trembling fingers, or strain to hear the cockcrow over the scream of the steam whistle if dawn will arrive in time, or we see her trying to cool or divert the water in the boiler of the onrushing steam engine with her mind powers.

I call this the ‘Jack Vance’ problem because Jack Vance, of all authors who tackled the problem, came up with the solution that was the most elegant: he established that the spoken syllables of the spells warped reality only in the particular way each spell was designed to do, but that the warlord, the moment he pronounced the words, forgot them, and could not recall them again until he returned to his manse or tower to pore over his tomes, librums, grimoires and folios in which the precious spells were written. (Fans of Dungeons and Dragons will recognize this immediately as the basis of the magic system of Gygax. Game masters, like authors, have the same problem on how to allow magic into the hands of protagonists, without it overwhelming the story.)

For the record, the poorest solution to this problem I had ever seen was in the children’s cartoon SHAZZAN. True enough the genii could not be summoned unless the two teen protagonists touched the severed halves of a magic ring together and spoke his name, so that tense scenes could be made merely by having the two locked in separate cages or the like. But once the maniacally laughing genii arrived, there was no limit to his powers and no consistency, so that the fights were as boring as possible, even to a child’s eyes. Since anything could happen, nothing meant anything.

Much as I enjoyed, and even loved, much of the Harry Potter books, the part with the least joy for me was whenever a duel of magic was fought, because the author never made clear, at least not to me, what magic could and could not do. So when Voldemort raises a wand and points it at Dumbledore and utters an unforgivable killing curse, Dumbledore … does what? Parries? Dodges? Draws a ward? Utters a counter-curse? Closes one eye? Holds up a crucifix? Uses a Substitution Jutsu? Calls on Ryle, Scourge of Demons? Someone more learned in Potter lore than I must answer.

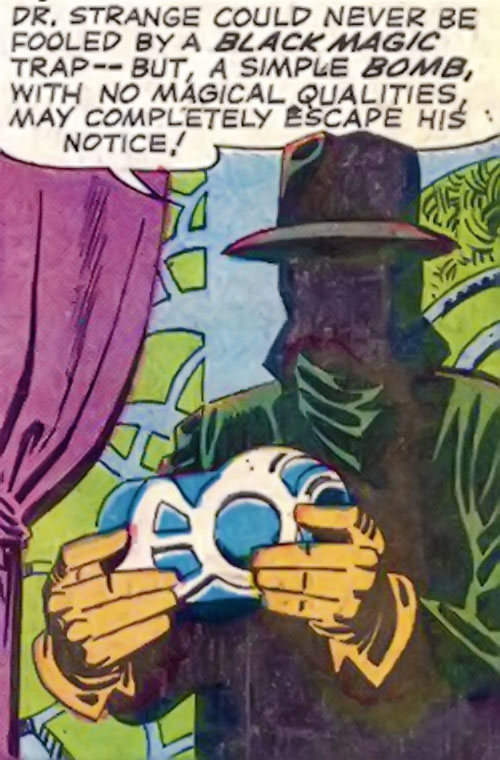

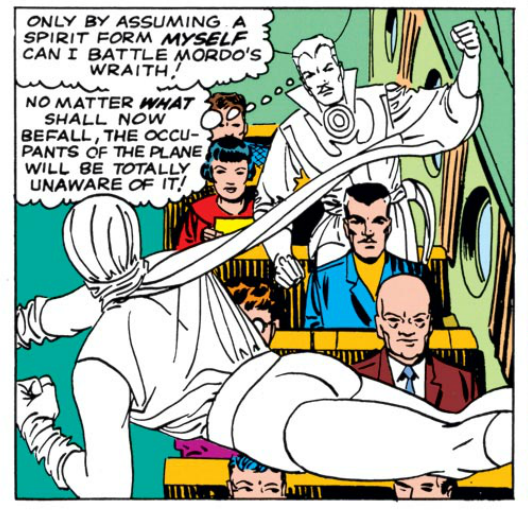

Surprisingly enough for a book written by many hands over many years, the comic version of Dr Strange did not have this problem, or did not have it to the same degree. While, from time to time, lazy writers would grant Dr. Strange the use of some new and potent spell he never used before, for the most part, he was confined to several clear abilities: he throw or parry bolts of invisible ectoplasmic energy, or use such energy to bind or trap a victim spiritually, could hypnotize the unwary, read minds, cloak himself in an hypnotic illusion, project his astral spirit from his body, to soar unseen or to enter dreams, use his magic amulet to dispel curses and shatter illusions, or use his cloak of levitation to fly. Other spells would be introduced when the plot required, as when traveled to other dimensions, or through time.

However, he could not, as best I recall, heal the sick or raise the dead, or even stop a mundane bomb from going off. In one of the more dramatic episodes in the early comics (Strange Tales 142-143), he is trapped by enemy disciples of Mordo, and blindfolded, gagged, and his hand bound in gauntlets, so that he can speak no spells and make no mystic gestures, although he can still project his astral self outside his body, and see what his hooded eyes cannot, and still control his cloak of levitation by thought alone. Dr Strange was that rarity in weird tales, a magician who is not all powerful in an understandable way.

With all this in mind, when I heard that Marvel was making a Dr Strange movie, I was torn between anticipation and dread. Dread, because political correctness ruins everything it touches. Anticipation, because Marvel films has made movies like GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY, and CAPTAIN AMERICA, and AVENGERS, which rank so far above even other Marvel properties held in other hands (FANTASTIC FOUR, SPIDERMAN) as to earn the lauds of every superhero fanboy now alive. We live in the Golden Age of superhero films, largely due to Marvel Films.

THE REVIEW

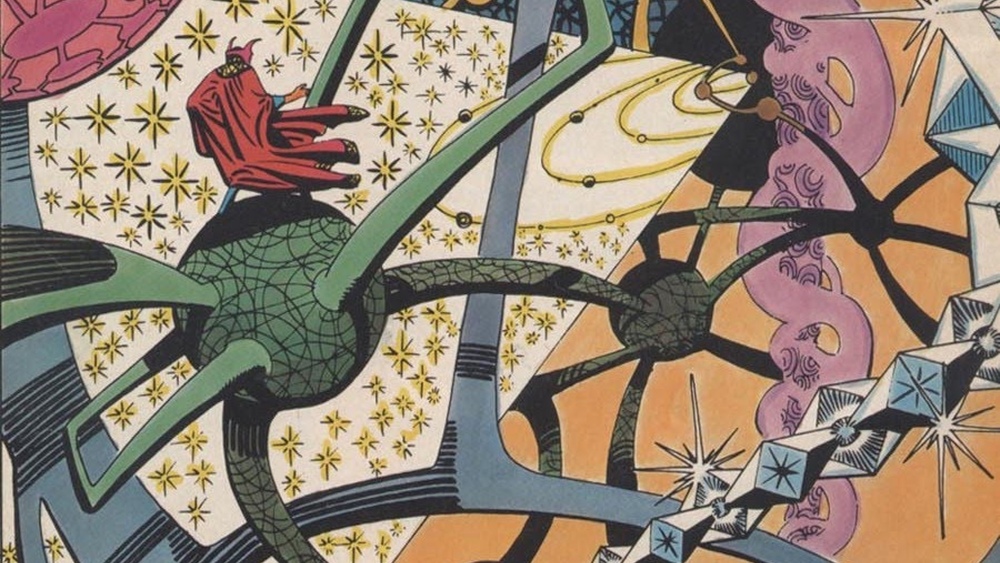

The first thing to be mentioned in any review of this film are the visual effects, which are splendid and awe-inspiring, and correctly capture the eerie and mind-bending effect the comic splash pages portraying such phantasmagorical visions were meant to convey.

A single line establishes that there is a mirror dimension, occupied by all the objects and sights as ours, yet invisible to mortal men, but which can be bent and folded like origami, so that the whole landscape becomes a weapon.

While this is reminiscent of some of the visuals in INCEPTION, the film takes such brilliant advantage of the idea as to have battles where the hall or the whole horizon might switch from vertical to horizontal, or a man fall out a doorway only to find himself plunging down a well.

The only other equally brilliant yet dazzling and clever use of a spectacle like this, as good as this, is another scene in this same movie. The magicians are battling in a scene that is rotating backward through time around them, but during a widespread disaster reversed in time, so the fighters see fallen towers gathering their bricks and leaping upward, explosions gathering back into unharmed gas lines, and smashed windows jumping backward into order, but they must dodge the reverse-flying debris while fighting each other.

Indeed, I have only two small complaints about the visuals. First, in the fight scenes, the camera is often too close and jumps hither and yon in too jerky a fashion to see what is going on.

Second, in the comics Dr Strange and the other magicians battle using bolts and shields of energy that flies from their fingers, whereas in the film, the fights were rendered as kung fu action, with magic being used only to produce weapons made of energy held in the hand. This second complaint is a matter of taste rather than a mark against the film, but it struck me as out of place for a doctor with wounded hands to be acting like the Karate Kid.

But, like THE MATRIX, like DARK CITY, while the visuals are the first thing to be mentioned, they are not the spine that holds the film. The plot is.

The plot not only is based firmly on the source material (this version of Dr Strange is indeed a worldly man, seduced and jaded by material things) but improves upon it, filling out details and adding needed perspective and shading to give the events weight.

As in the original, Dr Strange is a wealthy, selfish, self-absorbed surgeon whose hands are damaged in a car accident, ruining his career.He spirals into self pity and strong drink, but follows whispered rumors of occult secrets and miracle cures to the far east, where he meets the Ancient One, and the Ancient One’s disciple, Baron Mordo. At first he is skeptical, but then…

In the film, this whole was handled with a neat economy, introducing a love interest to act as a foil for Strange’s descent into ruin, giving him a specific set of clues to follow. More skillful was the decision to give the main villain from the comic a clear and sympathetic motive for his villainy.

There are two weaknesses in the plot. First, the film makers, like those who filmed the atrocious JOHN CARTER, decided to put onstage in the first moment of the film the splendid special-effects extravaganza that in both cases should not have been introduced until much later, when the viewpoint character first encounters these odd and splendid sights. One is always supposed to start a quest into the strange and beautiful golden wood of he elfs, the lonely mountain of the dragon, or the dark lands of the dark lord from a quiet and quotidian place like the Shire.

Second, like all superhero origin story films, the first act has to say how he gets his powers, leaving the introduction of the villain and the build up of the the stakes to the second act and the fight scene to the third.

Some films can meet this problem by simply taking the time to tell the origin story and then telling the story of the villain and his plot and how the hero thwarts it. See the original SUPERMAN THE MOVIE by Alexander Salkind for an example of how to do this without rushing matters.

Some films can avoid this problem simply by side stepping it. See THE INCREDIBLES for an example of that. The backstory there simply assumes some people have superpowers, and no mention is made of how they got them.

This weakness is present here. The evil magician, whose name I cannot recall (he is not from the original comic) seeks to open the portals between Earth and the sinister Dark Dimension, where the ulterior and infinitely powerful Dormammu dwells (I recall his name because he is from the original comic, and is, indeed, one of major villains of Dr Strange’s universe). The motives of the evil magician are given in a short speech when Strange has him momentarily chained up, and it is a good and solid villain motivation, too. He wants to overcome the tyranny of time and escape the doom of death: as who does not?

But the big bad is otherwise not that big or not that bad. He does not have anything like the snake-theme of Vordemort or the mechanical genius of Saruman the White to differentiate him from any other magician one might name. In a samurai movie, each opponent fought is supposed to have a signature weapon or signature move to make him memorable. Not here.

In the first act, Dr. Strange is utterly incompetent while being trained in the mystic arts by the Ancient One, but by the third act, he is suddenly able to go toe to toe with masters and of long experience. This some might find jarring.

Now, to me, this leap from novice to front line fighter this is not as jarring as it seems, because, first, he is thrown into the situation by a sudden attack beyond his control, and second, in that fight he is only shown using powers he was already trained to use, but — and here is why I like the film so much — he uses them cleverly.

I spoke above of the twofold balancing act needed in any weird tale where the hero is a magician. First, if he uses occult powers, they must seem dark and spooky, or otherwise they are not occult. But if the occult is too dark, or too much like real occultism, the man is not a hero. (This problem is particularly acute for faithful Christians who hold it as an article of faith that occultism is devil-worship, and the slippery slope down to damnation.) Second, the powers have to be limited and defined in such a way as they can be used to awe-inspiring effect (a magician who cannot do awe is no magician) and yet not do everything and anything.

The film neatly sidesteps the first issue using the same figleaf as was used in the first THOR movie. Instead of simply saying the Asgardians were pagan gods, it was said they were otherdimensional beings once worshiped as gods by the Norse. Here, the Ancient One says that the skeptical Westerner can call the arts she teaches ‘spells’ if he wishes, but if that word offends him, to think of it as something like a computer programmer hacking the fundamental code that runs the laws of nature. In other words, the magic here is called magic, but it might or might not be.

On the other hand, the one character who does do something that is clearly diabolism, that is, making a bargain with an unclean spirit in return for power, is unambiguously a betrayer and a bad guy. So this is not an advertisement for necromancy.

The second issue is handled simply by keeping the magic showed in the film simple, clear, and mostly visual. The teleportation through a Saint Catherine’s Wheel is established with a simple rule: if you lose your magic ring, you are stuck, maybe forever. The rule for the mirror dimension is that it bends and folds by the will of the magician, who can therefore throw his foes up the slopes of bending buildings or through magical closet doors into arctic oceans or drear desserts. Or they strike and parry with glowing kung fu weapons conjured out of air, but these act like light-sabers or any other kung fu weapon. The amulet of time alters time; the cloak of levitation levitates.

It should be said that the cloak is a character in his own right, a bold and funny a silent sidekick as the carpet from Disney’s ALADDIN, so do not mess with either. And the cloak is not too far off from the way it is portrayed in the comics.

But the magic in the film cannot do everything. It is limited, and the limits are clear to the audience. Indeed, in the stunning climax of the film, which I would not dare to reveal or spoil, not only does Dr. Strange use a trick we have seen him use before, and not only is it used on someone we have good reason to believe is vulnerable to it, he uses the deleterious side effect of the trick, that is, he traps himself by deliberately invoking one of the drawbacks he was warned not to invoke. He outsmarts the powers more potent than he, not outfights.

The acting is top-notch, as good as anything seen in GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY or AVENGERS. Benedict Cumberbatch has the look and attitude of Dr. Strange down perfectly, both as the worldly man seduced and jaded, etc., in act one, and as the mystery man fending off hidden horrors in act three.

What about swapping the sex and race of the Ancient One and Mordo?

Like I said, I was prepared to hate this movie having seen too many examples in the comic world of politically correct nonsense of late to have any patience left. The last straw was when they decided to turn the Ghostbusters into unfunny dames.

The problem with the Ghostbuster remake is that if the dames are not funny, the film makers cannot make the audience laugh by accusing the audience of misogyny. Not laugh at the jokes in the movie, I mean.

If this swap of the Ancient One for the Bald Dame and the switch of Baron Mordo for Black Mordo was meant as a genuflection to the gods of the politically correct, it backfired badly.

Both the Chiwetel Ejiofor and Tilda Swinton actress were convincing, even mesmerizing, in their roles. Both of them played the parts so well that the audience was colorblind to their race and sex — and colorblindness is the one thing the political correctness mavens cannot stand and cannot permit.

But when a black man plays a character hitherto depicted as white, or a bald woman portrays an ancient oriental man, and each one does such a good job that no one cares, it is not a victory for political correctness. It is a resounding defeat. Anything when all men are judged not on the color of their skin but on the content of their character is a defeat for political correctness.

So if, like me, you are eager to hate films that have black actors or young actresses stuffed awkwardly into roles originally played by Transylvanian men or Tibetan graybeards, if you are like me and judge all folk by individual merit, not by a lazy group identity, you will judge the casting here to have been just fine.

Now, we will never know what it could have been like if Victor Wong or James Hong had played the role of aged Oriental mentor, but Tilda Swinton did a good enough job, perhaps the question is moot.

One reason why I liked the acting here is that the actors were given something to act. Each of the main characters (but, oddly, not the unfortunately flat and uninteresting villain) has a character arc. As befits an action-oriented superhero movie, do not expect a complex character study, but there is more here than one might expect at first.

Dr. Strange has the character arc defined by his introduction, a worldly man seduced and jaded by material things who left us behind and strove to stand against the unseen subtle perils of the other world. But the film makers added more layers to this, because even when he was a selfish surgeon, we see him going to great lengths to save lives (even if he only does it in situations where he can gain glory and applause).

But he has two bars to clear, not one. He first must overcome his disbelief in magic and prove his persistence (he is kept waiting out in the rain just like the young Kwai-Chang Caine in the show KUNG FU my readers are probably too young to remember), and then he must next volunteer to fight in a war of which he was hitherto unaware, and which has no claim on his loyalty, other than sheer altruism.

Perhaps the call to adventure of the reluctant hero is what one expects in a superhero origin story. But this is given a sharp sideways twist, in the scene when he first discovers that he is caught in the unseen war, and he kills a man, we discover that he actually takes the Hippocratic Oath quite seriously, and refuses to use his powers to murder — a decision for which he is upbraided by Mordo, hitherto his friend, who regards it as fastidious, if not downright cowardice.

Mordo likewise in the comic is a simple, one-dimensional character with no particular motivation, and, after he is revealed to be a coward in Strange Tales 141, really never becomes a legitimate threat again. But here, he is handled as being a man of principle, who, when his principles are offended by the necessities of the situation, has to decide when and whether the ends justify the means. This character arc is made deliciously ironic by the fact that in the beginning he argues vociferously in favor of the opposite of what he himself decides by the end.

And, again, in the comic the Ancient One is simply the mentor that any Oriental Sage is meant to be. Like Mr. Miyagi from Karate Kid but without he sad backstory, or like Merlin the Magician but not tempted by bathing beauties. He is more or less the Aunt May of Stephen Strange, although he helps out via remote control by telepathic warnings.

Here in the film the Ancient One is not so one-dimensional. We discover that a dark secret is behind the ancient age of the Ancient One, throwing all loyalties in doubt, and the character is deep enough to speaks poignantly about the mystery of life and death when she and Stephen are watching a slow motion rainfall together. As the drops fall, she talks about the nature of life and death. It was an unexpectedly moving moment to find in the midst of a summer blockbuster. It reminded me (albeit it did not equal) similar moments from Disney and Miyazaki.

I tend to rate films based on five things.

In a special effects extravaganza, I give one star for the visuals if they impress. Here, I was more than impressed. The visual effects not only stunned the eye, they captured the twisting non-Euclidean creepiness of discovering that there are more dimensions than you thought to the universe.

(This first star is always relative to what the film is attempting to be. Had it been a musical, I would have rating the music and dancing, and had it been a war flick, I would have rated the battle sequences. Sci-Fi gain or loose the first star in my book based on scientific accuracy.)

I give one more for the clever use thereof (which is not the same thing. Some films can be pretty without being smart, see, for example JUPITER ASCENDING, which was gorgeous by somewhat empty). The weightless, gravity-flipping disorientation was always clever: as when the bad magician, rather than dodging a car, merely splits the scene in two and walks into a space that was not previously there.

I give a third star for the acting; and a fourth for the character arcs, which were surprisingly weighty and realistic for a superhero action flick.

A final star I give because the film was true to the source material. True in tone, that is, not in detail. They changed a number of things, but either the change was excusable, or welcome.

Let me emphasize this point. There was a 1978 pilot starring Peter Hooten, in which Dr. Strange was a kindly GP doctor, Clea was an earthgirl and local co-ed, the Ancient One was Merlin the Magician, and the villainess was Morgan le Fay. It kept nothing about the original comic except for making Wong the manservant. It had its good points, and I liked the soundtrack, but it simply was not true to the original. As a purist, I have to give a star to any film which treats its source material with respect.

If I were a more careful reviewer, I might subtract one star for a scene at the beginning where a librarian is decapitated. It was pointless, and it is not the way a magicians, who can kill victims with curses rather than knives, should behave. It did not fit the tone of the rest of the film. However, I would add that lost star back in for the portrayal of the Ancient One by Swinton: she is described as being compassionate while merciless by one character, and the character we see on the film convincingly matches the description.

Also, I might restore a lost star for the number of little nods to the fans that are kept in, small details like getting the address of Dr. Strange’s house in Greenwich Village correct, or showing the Stark Tower in a pan shot of the New York skyline.

Are there any other errors or drawbacks?

Some critics I have heard were unmoved by the humor and the quips in the film. I thought some of Dr. Strange’s jokes were meant to express his discomfort with the oddness of the new world his discovers, and so they are meant to fall flat, which is part of the joke. I thought it was hilarious that Wong did not laugh at his jokes, until, at last he does. Humor is hard to do even under the best conditions, so I cannot promise you will be as amused as I was. Tastes differ.

Other critics criticized the scene were Dr Strange is mortally wounded, and in his astral form, appears before the astonished eyes of his ex-girlfriend, a surgeon, who is operating on him in the operating table. Meanwhile another evil magician in the astral world, invisible and impalpable, struggles with strange. They do battle while in the mortal world the only hint that dire deeds are being done unseen are the odd sounds or the flickering of lights.

Those critics, I suggest, are simply out of their cotton-picking minds. I would call it the best scene in the movie. It comes more or less straight out of the comics, so it is both good, and true to the original.

Not only is the race against time in the operating theater tense, as is the weightless fistfight in the astral plane, and not only is the slight way in which the two overlap is once again used cleverly, but this one scene in miniature captures the mood and the meaning of everything stories like this are supposed to be about: invisible menaces hovering thick and black about our mortal existence which we cannot see or fight, but which the lonely enlightened man, the sage, the magician, can and does.

And the poor, benighted mortals meanwhile remain totally unaware.

Perhaps the critic here was merely displeased because, after showing her a glimpse of the greater, darker, and mysterious occult world hidden beneath our unmagical mundane one, Stephen Strange did not take the pretty young surgeon with him, and show her the wonders. The critic commented that he would have preferred a scene like the one in SUPERMAN THE MOVIE where Lois Lane interviews the Man of Steel, who flies her out over the city in a moment of enchantment. Such a criticism is born of inattention: the wounded Stephen Strange was returning to a battlefield.

Also, this criticism missed entirely the point, the main point, of any weird tale of this kind.

As I said above, the weird tale where the hero has to fight a lonely and invisible battle against occult powers gets its drama and its flare from the fact that the fight is lonely and invisible. The man has left his mundane life; he is dead to his old life. He is born again, born into another world. He cannot go back and he cannot take anyone with him, except, perhaps, a disciple, as willing as he is to leave everything behind him and forgotten, all material goods and mortal obligations.

If anything in this language or mood of rebirth into a larger world reminds the reader of coming of age, joining the army, getting married, having a baby, killing a man in a battle, being baptized, or joining a cult, that is no coincidence.

Tales of other worlds are supposed to remind us of everything we do in our life that enters what indeed is a whole new world, one which, once entered, we can never leave.

Learning magic powers and fighting against evil sorcerers and demon-kings is indeed a smaller thing, a metaphor meant to serve as a concrete symbol of these greater things in real life. Tales of magic, if done right, remind us of how magical real life is.

Let me end the review by what I liked best, if I can refer to the scene without spoiling the surprise ending.

Dr. Strange, in the climactic battle, turns and flies away from the climactic battle. He goes to a dark place and says he wishes to bargain, but it is not really a bargain, not for him.

He comes to suffer and he is willing to die, and he does not fear the suffering for reasons we have already seen in the film. And, as befits a film about magicians, there is actually a sleight of hand going on.

Yes, it is a trick, and no, it was not the trick I expected.

At that moment, he has left the perfect selfishness of his old self far behind, and instead of seeking glory, he suffers in secrecy, so that no one on Earth ever discovers what he did.

And yet, again, as befits a movie about magic, when one dabbles with the dark forces, there is always a price to pay. The ending holds a note of well earned sorrow and regret.

FINAL COMMENT ON TRUE FANTASY AND THE OCCULT

This summer extravaganza film contains the same elements one might see and the best of fantasy tales. For fantasy stories are not meant to be mere escapism from the toils and troubles of quotidian life, no matter what critics suffering from a colorblindness of the imagination might say.

The best fantasy stories are meant to remind us of several things we all once knew but have since forgotten: First, evil is real and is immortal and is hideously strong, too strong for mortal man to overcome of his own strength.

Second, knowledge is not always good. There is a reason why, in stories of this kind, the books of the magicians are bound in chains and padlocked, or the books of the Sybil are scattered like autumn leaves in the wind.

Third, evil is self-destructive. Its own evil defeats evil, so that the weapon to be used, the only weapon to be used, is the one weapon evil can never understand and never handle and never draw from the scabbard: altruism, love, self-sacrifice, humility.

Finally and most importantly any story about the fantastic, the magical, the weird and otherworldly reminds us that this world is not all that there is. The heart leaps when we see fantastic tales about soaring figures adorned with splendid powers facing the dark and tyrannical monsters of the spirit, because our hearts leap with recognition.

Some may look askance at any tale where magic and occultism is glorified. I do not mock them for their reservations: the danger is real. My best friend from school was sucked into the sick world of the occult by wonder tales no more sober than this comic.

However, I have seen enough true fantasies, deep fantasies, that come from beyond the fields we know and which touch the deeper magic before the dawn of time, to be convinced that there is at least one pathway through the perilous woods of elfland into the broad and joyful country of light which Dante saw above the Earthly Paradise.

I have read stories of magical powers and hidden things that served as a lure to higher things, and met a librarian as fair and noble as a princess who as a child was lured into the bosom of Abraham by a children’s tale about talking animals and a winter queen.

Magic is a backward metaphor for miracle, and the occult secrets of the necromancer, if used rightly, can remind the lost and wandering imagination of the hidden mysteries of light of which mystics riddle and prophets thunder.

The dangers hovering thick and black about our fragile existence, of them we need no reminder. Every child knows dragons are real. Every adult can read a newspaper headline.

When the true tale of the fantastic speaks aright, it tells us is that there is a shining knight to slay the dragon, a prophet to confound the priests who serve idols, an exorcist to cast the demons back to the pit, and secret that brings hope without measure, a hope with no earthly cause.