Planetary: Mercury

In the Palace of Promised Immortality is a time-travel novella taking place on the planet Mercury, after, during and before the pregnancy, wedding night and birthday of Circe, the solitary time lady.

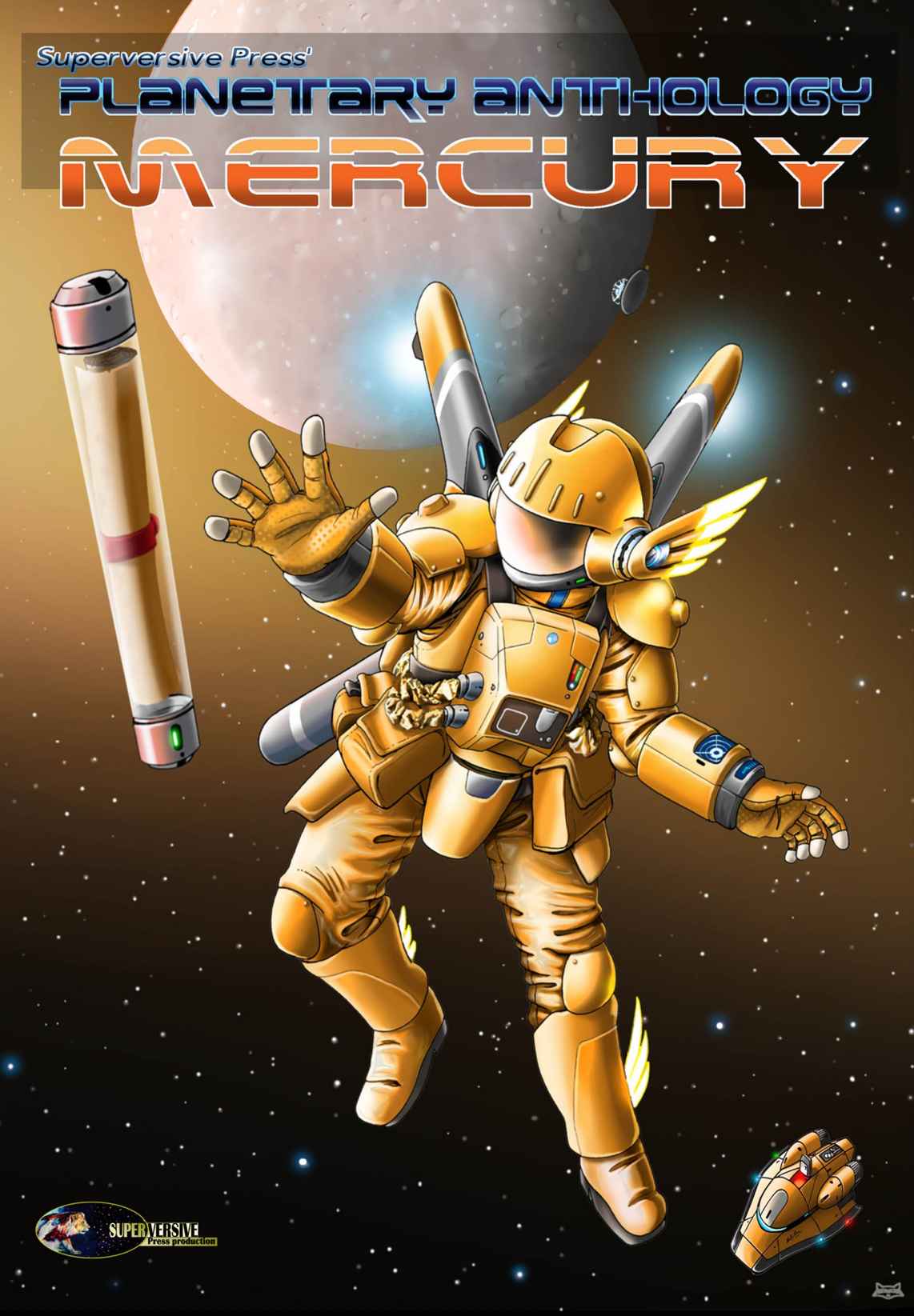

The story has the privilege of appearing in the PLANETARY ANTHOLOGY: MERCURY published by Superversive Press:

MERCURY!

Innermost of worlds, blasted by the sun by day and frozen by night, Mercury remains an enigma. Mythical Mercury was also the messenger and trickster, and known for blazing speed and wit. Here are thirteen tales of science-fiction and the fantastic featuring Mercury.

Throughout history, the planets of our solar system have meant many things to many people; Planetary Fiction explores the themes associated with these heavenly bodies as well as their astronomical, mythological, and in some cases even alchemical significance.

Included in this volume are

- In the Palace of Promised Immortality by John C. Wright

- Schubert to Rachmaninoff by Benjamin Wheeler

- The Element of Transformation by L. Jagi Lamplighter

- In Tower of the Luminious Sages by Corey McCleery

- The Haunted Mines of Mercury by Joshua M. Young

- Quicksilver by J.D. Beckwith

- Ancestors Answer by Bokerah Brumley

- Last Call by Lou Antonelli

- Deceptive Appearances by Declan Finn

- mDNA by Misha Burnett

- The Star of Mercury by A.M. Freeman

- Cucurbita Mercurias by Dawn Witzke

- The Wanderer by David Hallquist

My story? Glad you asked.

In this yarn, Mercury is the only planet in the solar system whose position near the sun warps timespace sufficiently for paradox-free time mirrors to operate.

In real life, Mercury’s day (which is 176 earthdays long) is twice as long as its year, (which is 88 earthdays). This means Mercury has eight seasons a year: a dayspring, daysummer, dayfall, daywinter, followed by nightspring, nightsummer, nightfall, and nightwinter. Each season is 22 earthdays long.

As you can imagine for a time paradox story, keeping track of the Mercury-years and Earth-years, and the ages of character or characters in this story was a turmoil of accounting.

Circe is raised by twins and crones from days to come to be the only time traveler in existence: a tyrant of time.

Once there had been others, or it had once been fated there would one day be, but now would never. Now they never had existed, nor ever would be, or, rather, now they would one day pass into the state of never having had been.

But, if so, who is the dark and handsome stranger whose locket has she found?

So young Circe begins to doubt whether she wants the Ouroboros labyrinth-knot of fate her older and wiser self or selves has planned out for herself.

(And, before you ask, this cannot take place in the same background universe as my Metachronopolis tales, since the mechanism and natural laws of time travel differ too widely.)

*** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** ***

Here is a free sample to whet your appetite:

1. Circe

She could not remember where she had put her memory eraser helmet.

Circe cupped the liquid of her pool in both her hands, and doused her face. She made her lips larger, redder, and her eyebrows darker, to allow her to pout and scowl more vividly. She focused two mirrors on her face, seconds before and after the change, and inspected the results critically.

Circe was half submerged amid the scented lilies and floating candles of the warm pool that served her as throne, wardrobe, and vanity. The bathing chamber was in her apartments that crowned the shining and soaring main tower of the Palace of Promised Immortality.

Naked, embraced by silky biomolecular-engineering fluid, floating beneath the dome of time glasses focused on the immediate past and future, she could make adjustments to her body, to hue of hair or feature of face, to foot or hand, or any measure of inseam, hips, waist, bust, height.

Discontent burned in her. Where was the helmet? What had been buried? She remembered the locket, and the face within, and remembered holding the locket in her hand. It was of utmost importance. It was precious beyond words.

Where was the locket now? Whose was that face?

The helmet had the power to call up buried memories as well as to bury them. Never had she needed it so badly. But why, now, of all times, was it not to be found?

She had certainly had the helmet within twenty-four hours ago. She had been assigned to babysit a bored and sulking little ghost. They had been playing hide and seek in the garden of forking paths surrounding the monument to Ts’ui Pen. Circe had been carrying helmet then, just in case some memorable but deviant event might happen, an event that could not plausibly be reconciled with her own memories from ten years past, when she first lived through the scene.

The chance of a deviation was small. Circe but dimly remembered the sharp-tongued and impatient babysitter who used to take her into the park for outings. To her young eyes, the teenaged sibyl had seemed very grown up. She had indeed shown up once with a book, a bottle, and the cylindrical amnesia helm. Where had the helm gone? What had the babysitter done with it? Circe strained, but the memory from when she was six, would not come to the fore.

It was not impossible that memories a decade old would fade. But twenty four hours old? She remembered waking up at the start of this watch; but not retiring to sleep at the end of the last watch. That was sixteen hours ago.

Circe could tell something was afoot. Soon after breakfast, the time mirrors began to grow sullen and stubborn when asked to show certain scenes. And, before lunch, during her history lessons, the golems were unaccountably slow in answering certain questions. (Of course she studied history. What else was there to study?)

After lunch, a middle aged sibyl, with her dark hair pinned up in a tight bun and crow’s-feet gathered at the corners of her eyes, had visited to tutor her in chronopathy. Circe stepped across a thousand years, futureward and back, across intervals large enough to be safe. These were lessons no golem could teach.

The matron seemed particularly curt, closed-mouthed, and cold. She frequently consulted her notes, as if to confirm that not a word of her dialog would differ from her recallled version. Circe, seeing this, resolved to write out her next diary entry with the wording changed.

Then a gray haired sibyl from near the end of her life, bent-backed and wrinkled like a prune, and leaning heavily on the middle-aged one, came to lecture her fiercely about the duties all time travelers owed their own future.

“Any act of disobedience, slouching, or sloth in performance, and you will erase yourself and die!” hissed the crone. “We who are downstream of you will not perish, however, as a slight adjustment to your past will prune you before you can act, and set the timestream right again before it goes awry.”

“You would kill me for slouching?” Circe had asked with sneer, rolling her eyes. “I make a terrible Mom. What if I decide never to have kids?”

The matronly, middle-aged sibyl grabbed Circe’s ear and twisted it painfully, making the girl bow and yelp. “Today of all days, will you give us cheek? Use your ear or I will rip it off.”

“It comes off you if it comes off me!” Circe snarled, “You are not my real mother, anyway! Where is she?”

The crone laid her withered hand on the wrist of the matron. “This does not sound quite right to me.” She whispered. But the younger sibyl said softly, “This is the way I remember it. Let us depart before any changes are introduced.”

Without any ado, the two vanished through their different mirrors.

That confirmed Circe’s suspicions. Changing insignificant events she had seen sibyls do thoughtlessly, or out of a sense of wicked pleasure. Her older shadows grew cautious only when massive happenings were afoot.

That had been an hour ago. Circe did not usually bathe before dressing for dinner, but she wanted to sooth her bruised ear. She ignored the dinner bell when it rang. Let Cook and the serving maidens keep her supper warm for her.

Circe touched one of the waterlilies with her finger, and told it expand to giant size, and fold its petals just so, to allow her to sit on it as it floated in the water. The biomolecular fluid penetrated into the lily and worked the alterations. Circe climbed into it. Perfume escaped the petals where her weight bruised them.

2. Springtide

Windows circled the walls of the bathing chamber. These were made of space glass rather than time glass. These panes could bring into clear view any object within the circle of the horizon, or bring physical objects.

The horizon displeased her: it was too close, too narrow. The horizon of Earth would have been three times further away, and the sun would have been three times smaller.

In the view, underfoot and close at hand, were the wings of the Palace of Promised Immortality, including the museum holding the artifacts, archives, and prophecies taken from all periods of future history from the current epoch to the Final Extinction in A.D. Three Billion, when the sun was destined to overwhelm the inner planets, and all life die.

The shining towers, sheathed in silent energy-auras, rose sheer from the waters of a central lake in the middle of a vast impact basin called Caloris Planitia. This basin formed the floor of a crater of the same name. It was wider than Texas. At noon, each second perihelion, this crater was in the closest spot to the sun of any bit of ground in the solar system. It was an act of overweening engineering to build an oasis of earthlife here.

Arbors, gardens, vineyards and cropfields ran from lakeshore to the horizon in orderly rows and rectangles; it was a pleasant patchwork of emerald hews. The channels and cracks of the Pantheon Fosse radiating outward from the lake were river canyons filled with streams, fishponds, and rice paddies. Fountainworks fed tiny, bright streamlets running to and over the canyon walls in the musical silvery threads of countless waterfalls.

Over the horizon and beyond her current view, four hundred miles of dark forest grew wild across the plains and up the knolls and bluffs to the continuous mountain-walls circling the crater. This unbroken forest was void of animal life, silent and without birdsong. No goats skipped amid the foothills, no sheep grazed in the meadows. Only the droning of bees was here.

The miniature planet was equal in surface area to Asia and Africa combined, and it was all her own private estate, or so she had been told. For a girl living in solitude, it was appallingly huge and bare, and lonely.

Shadows visited her, of course, sometimes in throngs: ghosts from her past and sibyls from her future. But, technically speaking, she was still alone.

Golems did not count. They were furniture.

Circe scowled at the swollen, slow, and sluggard sun. It was low in the east, but neither reddened nor oblate, since there was no atmosphere to distort it. Dawn had been two earthdays ago; noon would not come for another forty-two.

The sight of young buds and green branches, and the scent on the warm breezes entering the space mirrors displayed the springtide. The axial tilt of Mercury too slight to contribute any seasonal variation, but so eccentric was the orbit that the difference in distance from the sun between perihelion and aphelion ushered in globe-wide seasonal variations.

Sunrise to sunset was eighty eight days, one year, while the full day-night cycle was twice as long. Odd numbered years held four seasons of light: the buds of spring came at dawn; the warmth of summer burned the noon; the harvests of many-colored autumn came to full fruit in the afternoon; and the frosts and snows of winter turned the dusk white. Even numbered years held four seasons of darkness: the scented night-breeze of the springtide evening led to the showers of summery midnight; then a season of mists and fogs when the golems trudged through moonless darkness to reap a second harvest of the night crops; then came the clear cold night winds of winter before dawn.

The world should have been a molten hell by day, a frozen hell by night. The energy dome shielding the vast Caloris Basin did not seem like technology to her. It seemed like magic. The sibyls told her this art had originally come from twenty centuries in the future, from the cruel days of the Glorious World Empire of Tsan-Chan of A.D. 5000.

The biotic engineering that had created perfect replicas of earthlike plants yet able to sprout and ripen and fade in twelve weeks, to her was also magic, as were the strange fruits and nocturnal flowers designed to live and bloom without light. This art came from A.D. Five Hundred Million, when the highly-modified Biomancers of the supercontinent of Pannotia ruled a single landmass supporting single interconnected treemass filling the hemisphere.

The psychomechanical engineering that had created unfree yet living human-shaped artifacts to act as the serfs and gardeners, tinkers and tillers of the Palace of Promised Immortality came from the time when the Great Brains ruled the Vendian supercontinent. These were a race of immobile supermen whose nervous systems were forty-yard-wide masses floating in lakes of buoyant nutriment, from which their shriveled bodies hung like the stems of mushrooms. Their cold, intellectual empire arose a hundred million years after the Biomancers, for the Great Brains had exterminated their creators.

To create the golems, make them able to think, but not able to form desires nor act on them, that was something Circe did not think was magic. She thought it was black magic. She thought it was witchcraft.

From here, she could see the golems toiling, stooping in rhythm amid the rice paddies. They wore masks of white, with only the narrowest slits for mouth and eyes, to display their lack of humanity. All had female bodies, including the serfs tending the rice paddies and harvesting crops. No servant shaped like a man was permitted.

The science behind the time mirrors came from various eras, for it was easily discovered, and yet it even more easily eliminated itself and its discoverer. Circe had never been told the name or native year of the first time traveler, nor did any sibyl know.

Physical motion of the body through time was possible on Earth and Venus, but more deceptively fatal than quicksand. This was amply shown by the catastrophic paradoxes that haunted the Imperial Princess Shammuramat of Tsan-Chan when she attempted to use time travel as a weapon against the insubordinate yet all-powerful Gunsmith Guild of the Fifty-First Century.

Mental projection was safer, and could take place on Earth. The experiments of the magician Nun-Soth of A.D. 16000 involved the first surviving unambiguous record of chronopathy, the power of casting the soul through time as a shadow; but that first, primitive mirror of the mind proved the aperture was two-way. Disaster of another kind struck.

An age of dark conquests followed, when savants descended from Nun-Soth cast their minds back to his era, emerged from the mirror, and overwhelmed the souls and possessed the bodies of the priestkings, theurgists, janissaries, satraps, and savants of that generation, or anyone else who might have organized a cadre of resistance.

For four thousand years they ruled, but even their ability to foresee the coming night could not avert it. Civilization collapsed. The vampiric thaumaturge Si-Seneg, the Last of the Dark Conquerors, fleeing into the past, not only possessed the bodies of various figures from historic and prehistoric times, but taught the art to disciples in many eras. Twelve ancients managed to obtain or forge working time mirrors of their own, apparently from him, or from what he left. Into the farthest past he vanished, seeking the hour of the origin of life on earth. Of what he found, no record, no rumor told.

The art was lost. Civilizations rose and fell. The remorseless grindstone of Darwinian evolution, oft aided by the unwise meddling with human gene-plasm by ambitious vitalists and necromancers, ushered one humanoid or hominid race after another into being. Five more variant subspecies of subhuman, near-human and superhuman man arose, triumphed, flourished, waned, and vanished.

Not until A.D. Two Million was art of chronopathy found again, this time by a warlock-scientist named Trismegistus the Thrice-Greatest, a dread and dreaded egomaniacal tyrant, who used the art to make himself immortal. He commanded the peoples of Laurasia, the last inhabited continent above the waves, to worship him as a god.

With all surface metals exhausted by previous eons of mining, the Laurasians maintained a single global commonwealth with weapons and tools of wood and stone, glass and crystal, of subtle properties and great beauty, and tireless and titanic beasts bred to outrun locomotives, or winged leviathans to outfly aircraft.

Trismegistus destroyed any other shadows out of time he found projecting themselves into the savage centuries he ruled. He was a figure of mystery, having obliterated all records of his origin in order to spite future investigators, and prevent interference. His final fate was also hidden.

This maniac also destroyed all future rediscovers of the technique to come after him, down the corridors of time as far as he could project himself, slaying them before birth.

So again the secret was lost.

In A.D. Seven Hundred Fifty Million, in the time when Earth was like Venus, and the Rodinian supercontinent lay flat, stony and barren beneath the downpour of an endless storm that reached from pole to pole, there arose a posthuman race of philosopher-kings whose minds were too fine and stern for Trismegistus to penetrate, nor any shadows out of time.

The philosopher-kings rediscovered the technique, and cast their minds back through time not to domineer nor possess, but to console, advise and heal. They were immensely powerful, but crippled by their benevolence, so that no evils of the past would they ever undo. The sibyls taught her to despise and ignore their voices.

But even the philosopher-kings, in command of the secrets of time itself, could not conquer eternity. They could not undo nor mitigate the massive changes to the Earth eons of solar evolution ushered in.

A coleopterous race was destined to replace mankind, and to dwell in the cragged and volcano-torn supercontinent of Kenorland, in climes unfit for human life, in soils soaked with poison beneath thin skies hot with radiation. Their minds were difficult to penetrate. Few curious wanderers returned sane. Of their history, only scattered and incomplete records had ever been gathered.

The arachnid denizens of Earth’s final age ruled the melancholy eon three billion years hence when the final landmasses of Vaalbara melted to lava above the boiling world-ocean of Panthalassia. No written glyph, no artifact, had ever been recovered from the windowless and monolithic mirrored towers erected by the spider beings, nor from their hypercube-shaped orbital monuments. Only glimpses and fragments of wars and migrations returned from these future eons, gathered from the eye of lower animals whose nervous systems explorers from prior ages risked loss of mind and life to invade.

No future beyond those days could be seen, not from any coign of vantage on this globe, for Mercury in those days was finally swallowed by the sun.

All eons before that final doom of fire could be inspected by the long-range mirrors Circe had been told one day would be hers. Deep in this gravity well, the space was warped enough to allow a Schroedinger compensation effect to operate, and the links of the chains of cause and effect could be loosened.

Only here was it possible to pass mind and body through time without inevitable catastrophe. Here she was safe, for the chains of causation leading back to her ultimate origins on Earth had been severed entirely. Here, in this world named for the pagan god of magic, an object or an event could spring into being on its own power. Or even a person.

So she was told.

Circe doubted.

3. Nanny

She held up her damp hand, and told a time mirror to focus on it. “Show me what this hand held yesterday at this hour.”

But the image in the mirror showed her hand clasping that of an older woman. From the wedding ring on the finger, and the color and shape of the nails, she recognized it. It was the hand of Nanny.

The image also conveyed sound.

Nanny was saying, “I have been instructed to tell you this: The monthly cramps are debilitating, extremely painful, and must at all costs be avoided. Future records show your first is due tomorrow, just at dawn; your second two weeks before noon; your third a fortnight later; and another at dusk. Not only will the agony permanently wrinkle your face and scar your psychology, but the release of these chemicals and hormones into your bloodstream will alter your sexual drives and instincts, and making mates best avoided seem attractive.”

She heard her younger self saying in a sharp voice, “But surely these hormones are natural? And as for a mates … what mates? We are entirely alone on this terrible planet.”

Circe pulled the viewpoint out, so that not merely the clasped hands, but the whole scene was in the time mirror.

The image showed her walking hand in hand with Nanny. Nanny wore a black dress with puffed-out, leg-of-mutton shoulders, a stark white apron, a cap of lace. Nanny was masked, as ever, and no part of her face was showing.

Nanny was a golem, but the restrictions on her mind had been eased, so that she could nurse, teach, and play with a growing child. Circe adored the faceless oval of Nanny’s mask, as it was the only source of kindness she had ever known.

The two were walking amid early spring flowers in the high meadows of the mountain range just at the border of the energy dome covering Caloris Basin. Plinths along the hilltops marked where the dome surface intersected the ground. The cratered and airless landscape visible beyond the mountains was as black and pitted as floor of a furnace.

Circe saw herself, but dressed as she had been in September of last year, seven months ago. Earthmonths, she silently corrected herself with an audible sigh of annoyance. Mercury had no moon, hence no months.

The voice of Nanny from the mirror suddenly said, “Let us sit, and meditate, and enter the first-level betawave trance state needed for chronopathy. Clearing your mind of disturbances will clarify the answer.”

Circe saw Nanny and her September self flourish a cloth and lay it on the lush and flowering grass of the hill. Now they sat, and overlooked the burning land of airless craters beyond.

Circe remembered this scene exactly. Watch 2 of Year 64. It was the beginning of her discontent. She remembered meditating; but she remembered finding drowsiness, not clearmindedness.

Why this scene? The time mirror had mistaken her command, and found the image of her hand as it had been one hundred seventy-six earthdays ago, which was “yesterday” by the mercurial count, not the earthly. Circe was sure this mistake was intentional.

Circe was about to banish the image when Nanny turned her head and looked at her. There was no mistaking it: the narrow eyeslit of the oval mask was clearly looking through the mirror, right at her.

Circe was astonished. Only herself, and other versions of her, could see or manage the time mirrors. They were soul-locked. Servants, even high servants like Nanny, did not have desires and goals of their own, hence no destinies to change, and hence could not use the mirrors.

Nanny stiffened, realizing the blunder.

The truth ignited in Circe’s mind. Circe said, “You are me, aren’t you? All this time, I was raised by myself. My future self. Why am I dressed like a servant? Like a serf? Why am I pretending?”

The younger image of herself in the mirror now turned also, and saw Circe. “Oh, hello! Are you a ghost or a sibyl? What is going on?”

Without turning her head, Nanny calmly raised her hand, summoned the gleaming length of a command wand into her fingers, and before younger girl scream, dodge, or blink, sprayed the girl from the tip. It was biomancer fluid. The droplets were evidently programmed not to remold her flesh, but merely to stimulate the sleep centers of her brain. The younger girl sagged peacefully, and lay draped across the grass.

Circe said to the mirror, “I don’t remember you doing that.”

Nanny removed her mask.

She was her, of course. Her face was filled out, and a hint of a double chin clung to her jaw, and bags and lines of weariness underlined her eyes, but no strand of white touched her hair as yet.

Circe said, “I don’t remember you dousing me.”

Nanny said, “A touch of the memory eraser helmet will keep these events from forming a blister in the time stream long before it swells into a paradox.”

Circe said, “Where is my mother? Who is my real mother? Is it you?”

Nanny said, “An awkward question. All will be known in time.” She tilted her wand toward Circe.