Conan: The Black Colossus

The fourth published tale in the Conan canon, appearing in the June 1933 issue of Weird Tales, is The Black Colossus.

Some have dismissed this as a minor entry in the canon. I beg to differ: I hold that it establishes many of the basics which give one of the best beloved characters of this era and genre his particular strength and appeal.

This is one of the Conan stories of which I have no recollection of having read in my youth. I presume I read and forgot it. Looking at it with the eyes of age, I wonder that I did not see the wonders here.

It is the first story of Conan in his prime. This is the tale where Robert E Howard hits his stride in terms of the fury of bloodshed, the eldritch horror of the unknown, the passion of romance, and rough grandeur of his barbarian hero. Here is the Conan as he is commonly recalled by fond fans.

This story recounts one of the turning points in Conan’s career: his first command.

Recall that heretofore, we have seen him as a weary king staving off a supernatural assassination attempt (Phoenix on the Sword), then as a king deposed by treachery within and foes without (The Scarlet Citadel), then as a lusty youth, newly come from his rough northern tribe, living in lawless gutters as a thief and rogue (Tower of the Elephant).

Howard is a master of prose. Moreso than his previous tales, the words here were like rich and opulent jewels, cut and polished, memorable and mesmeric. I have read stuff said to be poetry less vivid than this.

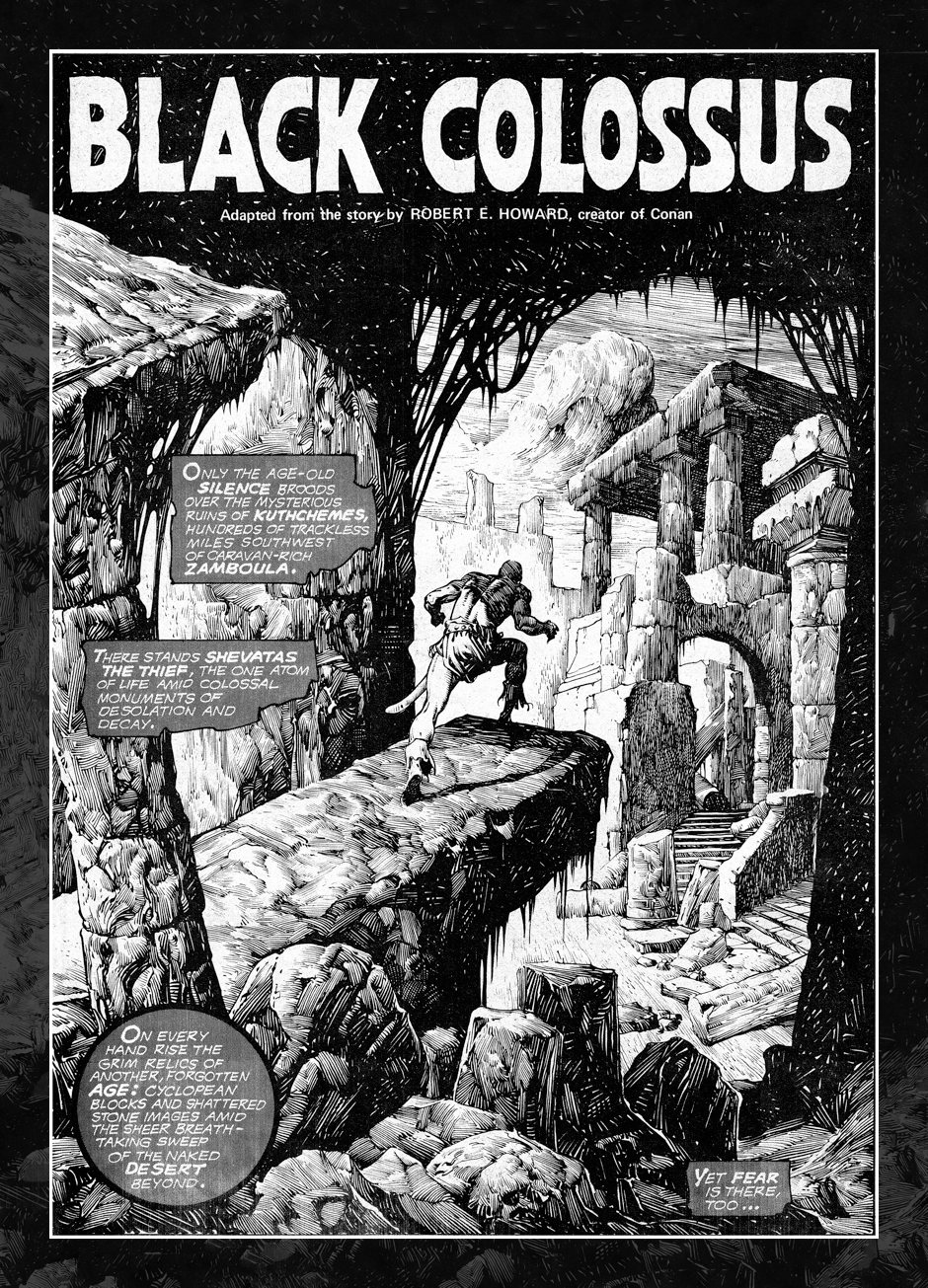

Here read the opening lines of the tale. Note with what economy the setting, mood, and tension are established.

ONLY the age-old silence brooded over the mysterious ruins of Kuthchemes, but Fear was there; Fear quivered in the mind of Shevatas, the thief, driving his breath quick and sharp against his clenched teeth.

He stood, the one atom of life amidst the colossal monuments of desolation and decay. Not even a vulture hung like a black dot in the vast blue vault of the sky that the sun glazed with its heat. On every hand rose the grim relics of another, forgotten age: huge broken pillars, thrusting up their jagged pinnacles into the sky; long wavering lines of crumbling walls; fallen cyclopean blocks of stone; shattered images, whose horrific features the corroding winds and dust-storms had half erased. From horizon to horizon no sign of life: only the sheer breathtaking sweep of the naked desert, bisected by the wandering line of a long-dry river course; in the midst of that vastness the glimmering fangs of the ruins, the columns standing up like broken masts of sunken ships—all dominated by the towering ivory dome before which Shevatas stood trembling.

A master wordsmith, Robert E. Howard is also a master of structure. The tale falls into four parts: the first concerns the hideous but unseen fate of a master thief who attempts to plunder a haunted tomb brooding over cursed ruins.

The second part shows the shadowy monster thus revived nightly tormenting a voluptuous princess with promises of his unholy lust for her. Nor is this her sole woe. The king her brother is missing, and the kingdom is about to be invaded by a prophet from the southern deserts leading a vast horde.

At the urging of her equally young and fair courtier, the princess supplicates one of the old, wholesome, northern gods: and is immediately answered by an oracle spoken from empty air.

The divine word tells her to turn command over to the first man she meets alone on the midnight streets. This, by no coincidence, is Conan the Cutthroat, Conan the Northron. He is merely one mercenary among many, if more unruly than the others, also more skilled a warrior. Despite natural objections, first he, then her officers, agree.

Conan is then clad in plate armor, stern and well-smithed, and when his captain of mercenaries, Amalric, who had been his superior officer an hour ago, tells Conan he looks like a king, the barbarian hears the shadow of prophecy in the words.

The third part finds the army of aristocrats and hired fighting men on the march. That night, Conan, standing guard over the sleeping princess, hears the frightened whisper and sees the ancient coin revealing the face of his enemy: the southern prophet is one and the same with the ancient necromancer Thugra Khotan, returned from the tomb. This same undead menace hovering over the princess by night is also leading the horde by day.

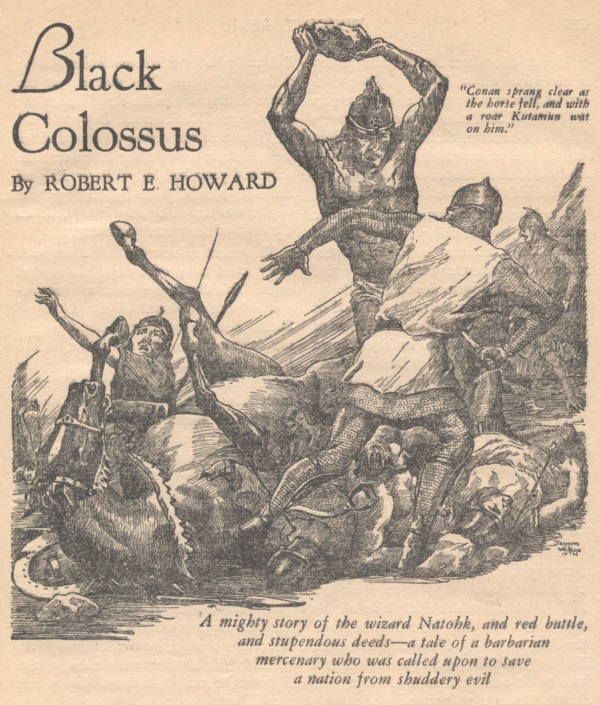

The fourth part is war, bloody and vivid.

The outnumbered chivalry and footsoldiers of Khoraja attempt to hold a pass against the countless charioteers, nomads, and wild horsemen from the south. Wizardry uses fogs and fires against them, and folly kills the flower of the knights. Against all odds, a secret footpath allows for a desperate flanking maneuver that breaks the ranks of the enemy forces.

Conan is battered nigh to death with a rock in the hands of a frenzied prince from the attackers; he survives and prevails; but the princess has been kidnapped from the camp by the demon-drawn chariot of the dark wizard, and his charioteer is an apelike thing not of this earth. He races away; Conan follows.

The rapid pursuit ends when the demon charioteer abandons his master and returns to the stormclouds above. A ruined temple is nigh. The necromancer drags the naked princess to an impious altar of black jade.

Conan bursts into the ghastly chamber. The hooded figure stooping over her rises, turns, and unveils its face, vaunting thus:

“Fool! Do you think you have conquered because my people are scattered? Because I have been betrayed and deserted by the demon I enslaved? I am Thugra Khotan, who shall rule the world despite your paltry gods! The desert is filled with my people; the demons of the earth shall do my bidding, as the reptiles of the earth obey me. Lust for a woman weakened my sorcery. Now the woman is mine, and feasting on her soul, I shall be unconquerable! Back, fool!”

An excellent curtain speech for a villain, complete with blasphemies against the gods.

Here I have a minor complaint: the climactic battle with the revenant necromancer from ages past occupies but a single stroke. Like Jambres and Jannes, the sorcerers of Egypt mentioned in Exodus, he knows the art of turning a wand into a serpent. So Thugra Khotan throws a snake at Conan, who throws a sword threw him.

This is too abbreviated for the weight of the event. The thaumaturgy that would topple the gods is nowhere in evidence.

Saved from a fate worse than death, the wildness of mutual passion sends the lovely, unclad girl into the arms of the brawny barbarian. He starts to object.

“Crom’s devils, girl!” he grunted. “Loose me! Fifty thousand men have perished today, and there is work for me to do—”

“No!” she gasped, clinging with convulsive strength, as barbaric for the instant as he in her fear and passion. “I will not let you go! I am yours, by fire and steel and blood! You are mine! Back there, I belong to others —here I am mine—and yours! You shall not go!”

He hesitated, his own brain reeling with the fierce upsurging of his violent passions…

The tale ends when he takes the slim white body of the maiden in his iron arms. The culmination is left to the lascivious imagination of the teen boy reading. Let it be noted that this is also the first tale in which Conan gets the girl.

The young princess is described in a luxurious prose that runs to the head like wine, at least for those whose mind’s eye is apt to respond to such imagery.

Minstrels sang her beauty throughout the western world … In her chamber whose ceiling was a lapis lazuli dome, whose marble floor was littered with rare furs, and whose walls were lavish with golden friezework, ten girls, daughters of nobles, their slender limbs weighted with gem-crusted armlets and anklets, slumbered on velvet couches about the royal bed with its golden dais and silken canopy.

But princess Yasmela lolled not on that silken bed. She lay naked on her supple belly upon the bare marble like the most abased suppliant, her dark hair streaming over her white shoulders, her slender fingers intertwined.

She lay and writhed in pure horror that froze the blood in her lithe limbs and dilated her beautiful eyes, that pricked the roots of her dark hair and made goose-flesh rise along her supple spine.

This all may be tame by modern standards, but, if so, modern standards are mis-calibrated. The magnetic allure of the brawny barbarian, the caveman, the beast only beauty can tame, may be a staple of lurid paperback romances these days: but I am not sure how prevalent the trope was in the 1930’s.

In any case, the dark, brooding and untamed Conan is in this tale portrayed as dangerously attractive to the female of the species.

This is more rare in science fiction than one might suppose: it is one of the things Pulps did well which the science fiction following John W. Campbell Jr did poorly. No hero of Isaac Asimov or Arthur C Clark is portrayed as even being aware of sex. The heroes of Robert Heinlein’s later stories are obsessed with it, but they themselves are singularly unromantic.

Later writers did also obsess about sex, particularly in the New Age, but they had the knack of either being clinical or pornographic rather than romantic. And the more modern science fiction abandons sex altogether for sexual perversion, which is disgusting rather than romantic.

The best parallel to Conan in science fiction, oddly enough, is Flash Gordon, which is one of the few space adventure stories were romantic lust is one of the main motivations of heroes, sidekicks, villains and villainesses alike: tormented Prince Barin pursues evil but lovely Princess Aura who has the hots for heroic Flash Gordon (as does Azura, Queen of Magic) and Flash is in love with the pure Dale Arden who is thrown into the scantily-clad space-harem of Emperor Ming the Merciless.

What of fantasy? I can think of few or no erotic masculine paragons in the genre: Eowyn is lured to Aragorn as Guinevere to Lancelot, but this is more courtly love. Frodo Baggins, Cugel the Clever, Rand al’Thor are not so described.

I note also that Conan is rarely half-naked in any story, but so far has been armed with helm and hauberk when going to war, but the illustrations prefer him bare-chested and bare-legged like a hero from the 1960 Hercules movies — who perhaps owe an unadmitted debt to Conan.

Several interesting themes also crop up in this tale, only lightly touched upon (as is to be expected in an atmospheric adventure tale), but trenchant nonetheless. Howard will return to certain of these ideas again in other tales.

One theme common to Conan tales is the pagan fatalism, so different from the virtue of Christian hope. It is said that martyrs could sing hymns in a lion’s den. Conan is portrayed as a pagan hero of the old stock, equally fearless, but clad in an iron stoicism. No bright hymns for him. His attitude is summed nicely in this passage:

Conan listened unperturbed. War was his trade. Life was a continual battle, or series of battles, since his birth. Death had been a constant companion. It stalked horrifically at his side; stood at his shoulder beside the gaming-tables; its bony fingers rattled the wine-cups. It loomed above him, a hooded and monstrous shadow, when he lay down to sleep. He minded its presence no more than a king minds the presence of his cupbearer. Some day its bony grasp would close; that was all. It was enough that he lived through the present.

That was all. Note the lack of flourishes and trumpets. Barbarians have no time for niceties, no tongue for philosophy.

An echo of this is found in the contrast between classes. Conan stories have a definite air of being blue collar: fantasy for the common man. The glorification of the rough, plain virtues of the barbarian over the corruption of civilization finds parallel in the glorification of the plain, rough fighting men over the gilded and dandified flowers of knighthood.

Whenever mentioned, the adornments and niceties of the knights are denigrated. There is no Aragorn son of Arathorn in a story of this kind, no nobleman whose true nobility is deeply rooted in ancient notions of honor, chivalry, courtesy, and courage. Far less is there any Brandoch Daha, whose jewel-encrusted finery hides the heart of the most ferocious fighter, in fence or melee, on the planet Mercury.

When Conan is first introduced by the princess as the new leader of her armies, the nobles turn to see him with his boots on the table, gnawing a dripping beef bone in both hands. A wry and inauspicious beginning.

As it happens, even with no training in generalship at all, the rough lad is able to grasp the simple principles of ordering ranks and files well enough to win victory against the fanatical armies of his foe, and his stalwart charisma can hold frightened men at their posts, or put heart back into their breasts. The tale implies these are not talents one needs aristocrat birth nor officer’s candidate training school to hone.

The Clausewitz of Cimmeria explains his theory of war.

“It’s no more than sword-play on a larger scale. You draw his guard, then stab, slash! And either his head is off, or yours.”

The point here being that a common man with common sense can do as well as one born and bred in the elite, or better.

The 1930s, please recall, was when the Progressive theory that experts and brain trusts could solve all the problems of complex civilization which unwashed commonplace commoners, with simple faith in common law or constitutional institutions, could not. The opposing opinion voiced by this story is striking.

This anti-elitist, democratic theme is subtle, but present in other scenes.

Count Thespides, the nobleman, has hair that is coiled and scented, a pointed mustache, satin shoes and velvet coat-hardie. It must be noted he is the third rival (aside from Conan and the necromancer) vying for the princess.

The chivalry of aristocratic sons he leads is described thus:

Their steeds, caparisoned with silk, lacquered leather and gold buckles, caracoled and curvetted as their riders put them through their paces. The early light struck glints from lancepoints that rose like a forest above the array, their pennons flowing in the breeze. Each knight wore a lady’s token, a glove, scarf or rose, bound to his helmet or fastened to his sword-belt.

This is contrasted with Amalric the mercenary and the common men he leads.

The tall horses of the cavalry seemed hard and savage as their riders; they made no curvets or gambades. There was a grimly business-like aspect to these professional killers, veterans of bloody campaigns. Clad from head to foot in chain-mail, they wore their vizorless head-pieces over linked coifs. Their shields were unadorned, their long lances without guidons.

… They were men of many races and many crimes.

These men obey orders, and due only to their discipline and fierce courage, turn the battletide and save the day.

The tale shows a nice bit of character development for our barbarian hero. At one point, Count Thespides upbraids Conan, saying it would be more knightly to meet the foe on the plain below the pass. Conan curtly refuses to join the battle until he has the advantage of ground. His old captain, Amalric, notes that he has grown sober with authority: back when he was a mere mercenary spearman, Conan would have been the first to join Thespides in reckless charge. “Such madness as that was always your particular joy.”

“Aye, when I had only my own life to consider,” Conan answers.

Fate is grim. For, at this same moment, Thespides disobeys Conan’s direct command, charges with lofty bravado into combat, and dies a hideous death by the unholy magic of the enemy, and all his loyal men with him. They perish instantly and in vain, not one of them touching sword or lance to foe.

There is perhaps a hint of E Pluribus Unum detectable in this tale, as in any tale where men of disparate backgrounds fight desperately against a common foe. The mercenaries soldiers of the little kingdom of Khoraja are described thus:

There were tall Hyperboreans, gaunt, big-boned, of slow speech and violent natures; tawny-haired Gundermen from the hills of the northwest; swaggering Corinthian renegades; swarthy Zingarians, with bristling black mustaches and fiery tempers; Aquilonians from the distant west. But all, except the Zingarians, were Hyborians.

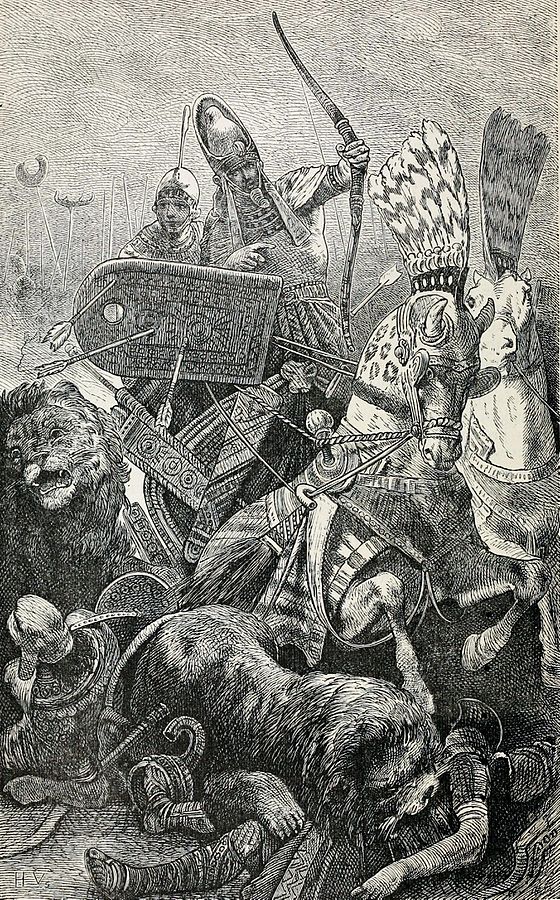

The soldiers of one band are adorned in armor from the High Middle Ages, while shoulder to shoulder with them are classical legionaries, Bronze Age charioteers, or Stone Age warriors riding naked into combat, wild hair flying, without saddle or bridle. This mix of arms and armor from different historical periods apparently strikes some critics as ahistorical or incoherent.

I dismiss this complaint: let not the tone deaf criticize Mozart.

Since the days when the Homeric heroes fought before the gates of invulnerable Troy, the warriors of the West are used to facing a diversity of Middle-Eastern and Asiatic peoples gathered in battle under vast oriental empires. It is an image deep in our cultural memory, at least as deep as images of the Fall of Rome and the decay of civilization.

The Battle of Carchemish, to take one historical example at random, was fought by Egypt and Assyria against the armies of Babylonia, allied with the Medes, Persians, and Scythians. I invite the reader to try to imagine the panoply of the heroes in helms conical or cylindrical charioteers, horsemen, hoplites, peltasts, archers, swordsmen with blade crooked or straight, spearmen, and barbarians mingled in such a mix.

Battle of Carchemish. Could Serve as an Illo for a Conan Yarn, No?

In the Battle of Kadesh, to pluck up another random example, the Egyptians and Hittites clashed at the Orentes river, and one was armed with bronze weapons, and the other with iron. Similarly, the battles of Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor to unify China, were fought across the weapon technology divide between iron blades and bronze.

Historically speaking, nearly any battle taking place overseas, on other continents, were meetings of different levels of military technology. Bronze Age Egyptian charioteers facing off against Medieval chivalry or Byzantine cataphracts probably never happened, but the battles between Crusaders and Paynim, Boers and Zulus, Cowboys and Indians, were fought across a wider gap in military arts.

But, leaving history aside, one of the main themes of fantasy is a sense of the fantastic. This includes, in war scenes taking place in a fantasy setting, the lush strangeness of the mix of many races, cultures, cults marching together under arms.

Think of the Cantina scene in Star Wars. If each and every bar patron had been an Earthman, all Englishman, the scene would have lost its point. But having the bridge crew of the Death Star be all Englishmen does not produce this disappointment precisely because it is not trying to produce this effect.

The bridge crew of the SS Enterprise, let it be noted, uses a diverse cast to produce the opposite effect: having white and black, Scottish and Russian, human and alien all aboard is not meant to impress the reader with their strangeness, but to assure us that races strange today on Earth will be brothers, not strange at all, compared to Tholians, Horta or Organians.

The rich descriptions of the alien weapons and soldiers, the mix of races, is a recurring leitmotif in historical fiction as in fantasy and space opera. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth as well as Eddison’s Mercury and Gene Wolfe’s Urth has such mingled armies drawn from disparate peoples, and nearly every imitator who followed them.

But leaving even fantasy aside, one of the recurring themes in Howard is the remorselessness of the grindstone of history. Barbarians and civilized men, stone and bronze and iron ages, are together cheek and jowl precisely because in the grim worldview portrayed, one race, one cult, one way of life is always ousting the other. Civilization supplants barbarism and is supplanted in turn by later barbarism.

Or, as the narrator notes when the princes is fearful of approaching the idol to Mitra, the devils of today are the gods of yesterday.

Nothing of Weird Tales or Robert E Howard fits into the neat narrative categories that hypnotize and stupefy modern critics, and make them worthless as critics. On the one hand, the modern critic of a politically correct bent would see the account of the admixture of races among the mercenary bands or multiracial empires as diversity therefore good.

On the other hand, Howard’s emphasis that the different races had different natures, attitudes, habits and collective personality characteristics gives each race its individual atmosphere and character, so to speak.

To the modern, that is racism, therefore bad. The modern makes it a thoughtcrime to think that various races might have family resemblances, a common ancestry, or any personality characteristics. (Aside of course from the two simple personality characteristics of “oppressor” and “oppressed.”)

The recurring Howardian theme of older, corrupt civilizations falling to the sword of healthier and hardier barbarians from the North is, as said above, the ghost of the Fall of the Roman Empire, at least in the account popularized by the Protestant northerner Edward Gibbon, which haunts so many fantasy and science fiction tales.

In the case of The Black Colossus, when the haunted ruin of the accursed city of Kuthchemes is described, its doom is recounted. It is told how, anciently, the city once held a sorcerer-king whose hordes and towers fell before the blond-haired Hyborian barbarians from the north, leaving only an inviolate and invulnerable mausoleum dome behind.

Those Hyborians are Conan’s ancestors. When the necromancer wakes from his tomb after three thousand years, the reason why Thugra Khotan gathers an army and gathers it against Khoraja, it is because, like Portugal, this is a kingdom conquered long ago by the blond, blue-eyed northern men. He bears a grudge against the race that swept his people into oblivion.

Thugra Khotan, like a single rock on the shore that continues to stand above the sea when the tide rushes in, is the sole survivor of the cataclysmic migrations of three millennia past. Such merciless cataclysms, migrations, disasters, and their strange survivals is another recurring theme often seen in Conan stories.

When he sees Conan, his words are “The arts which saved me from the barbarians long ago likewise imprisoned me, but I knew one would come in time—and he came, to fulfill his destiny, and to die as no man has died in three thousand years!”

This may be a reference to the master thief who died in chapter one. But if it is a reference to Conan himself, and the “one” mentioned means not “one man” but “one barbarian” then the boast is that Conan will die here and now, in partial payment, it seems, for the ancient enmity between northern and southern races.

Howard is fond of master thieves, especially those who plunder tombs or towers guarded by poisonous traps, fell beasts, and sinister spells. If you have every wondered why thief is a character class in Dungeons & Dragons, look no further than Robert E. Howard.

He is also fond of political intrigue. In the first four stories in the canon, a complex rather than a simple political situation is always presented. This is not Star Wars, where one monolithic evil empire opposes one monolithic band of honest and virtuous rebels, and no third parties are involved. This is not even Flash Gordon, where the various mutually jealous kingdoms of planet Mongo are all oppressed by the evil space tyrant Ming the Merciless.

The issue, for example, between whether or no to pay the ruinous ransom of the imprisoned king, and the fear that the greedy regime of Ophir may instead make alliance with the penurious king of Koth, is mentioned thrice in the tale, but never resolved. It does place the kingdom in the white hands of a young and unready girl, and the situation does prevent alliance with neighbors also threatened by the desert hordes of Thugra Khotan.

But the mention that the southern horde is no friend of Stygia, even though one rebel prince of the Stygian kingdom, Kutamun, seems at first a pointless complication. Later, we see this allows for the vividly described chariots to thunder into combat, and it gives Conan as specific and named foeman with whom to be locked in deadly and brutal struggle during the crucial moment when the dainty and curvaceous silk-clad princess is carried off by a black chariot drawn by a demon camel.

I suspect that Howard knew well that politics always involves degrees of alliance, intrigue, and betrayal. Civilizations never fall from the strength of the barbarians, after all. Civilizations commit suicide. Factionalism, quarrels between brethren, civil war, is what tears the towers down. And that requires a complex rather than a simple political picture to be on stage, one where more than one faction is in play.

The coiled complexity of the Howardian intrigues also serve a thematic purpose: it plays a sharp contrast to the straightforward barbarian hero, who cuts a clear path through all foes and obstacles toward his goal.

I noted one final theme in the work, that, frankly came as more than a surprise: it was a shock. Finding benevolent deities is as unusual in Robert E Howard’s work as in Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos or Joss Whedan’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

The benevolent god Mitra is described thus:

Behind an altar of clear green jade, unstained with sacrifice, stood the pedestal whereon sat the material manifestation of the deity. Yasmela looked in awe at the sweep of the magnificent shoulders, the clear-cut features—the wide straight eyes, the patriarchal beard, the thick curls of the hair, confined by a simple band about the temples.

This, though she did not know it, was art in its highest form—the free, uncramped artistic expression of a highly aesthetic race, unhampered by conventional symbolism.

The daughter of the priest explains the theology of the older, northern god in a paragraph:

“This is but the emblem of the god. None pretends to know what Mitra looks like. This but represents him in idealized human form, as near perfection as the human mind can conceive. He does not inhabit this cold stone, as your priests tell you Ishtar does. He is everywhere—above us, and about us, and he dreams betimes in the high places among the stars. But here his being focusses. Therefore call upon him … Before you can speak, Mitra knows the contents of your mind—”

There is an irony here. Howard inveighs against conventional symbolism, and yet in this selfsame passage, employs it.

I am, I fear, too Catholic in my outlook, and so in the sneer against conventional symbolism, I detect a hint of Puritanic distaste for stained glass, painted statues, vivid gold and crimson, images and icons and iconography. This, of course, is one with the Howardian dislike of hierarchy, of civilization, of settled convention.

The idea that the best things in life spring from a two thousand year old institution with rich centuries of thought and debate, clear laws, subtle philosophies, settled traditions, and that continuous civilization, not convulsion, not revolution, not solitary effort, is the source of all real growth and betterment in society, is a sentiment commonplace among Catholics. For many, it is a mood rather than a philosophy, but it is real. You cannot build the tower higher by retrenching the foundations, but only by building on the courses already laid.

It is a sentiment that must be put aside for a spell, if one is to submerge oneself into the themes of a Conan story, which tell the opposite tale. In Conan stories, old institutions are like old fruit: age brings corruption, not wisdom. Building a penthouse on a swaying tower with unsound and long-rotten foundations but hastens the collapse.

But the ironic contrast between the aesthetic theory and the theological theory cannot be overlooked. Mitra is a god none has seen face to face; he is omnipresent; he despises offerings of blood, preferring an upright heart and pure.

Images glorify Mitra but do not contain him, unlike the wood and stone images of the heathen, which are said to contain their gods, but are but dumb things. He dwells among the stars, that is, in heaven. And your father in heaven knoweth what things ye have need of, before ye ask him.

A more conventional picture of a benevolent god cannot be pictured, that is, a more conservative theology. And since it takes pains to justify statues as religious art, and contrasts them on the subtle theological ground that differentiates an indwelling spirit with what is merely a focus of attention, or an emblem, at this point we depart from Puritan theology and enter back into the older, larger world of Catholic thought from which it broke away.

In a story glorifying pagan ideals, the unintentional irony is delicious. Persons raised in Christian cultures breathe in its healthy atmosphere, and absorb its unspoken assumptions unnoticed. Even when they seek to undermine those foundations, they stand on them.

Howard correctly captured much of the fatalism, stoicism, futility, and, yes, even the grim frivolity of the pagan world. He can enter partly into the melancholy world of the pagans, or even mostly, but it seems he cannot enter fully. Souls even slightly Christian are grown too large to climb fully back into the playhouse of our pagan youth.

I call the world portrayed in this story frivolous because even the heated, passionate ending of the tale (demurely drawing the curtain before anything untoward is seen) is headed toward nothing but pain. Conan has no plans to wed the girl; she, for her part, has her rank and station to return to.

Fornication is more alluring than any other temptation in life. But once in the pit, there is no way out of it. After a long tryst or a short one, either he leaves her without a word to break her heart; or she, perhaps in coldness, perhaps in anger, leaves him; or they shake hands like emotionless and inhuman things, and depart each other without regret, their passions now cold ashes, as meaningless as dead stars and flowers never born. If she has a child by him, it can be thrown into the sand of the desert for the elements to kill and the winds to bury under the dunes. The little corpse has no name and no headstone to put it on.

But, in the end, fornication is frivolous because only marriage is sober. There is no other channel with walls steep enough to guide the rough and wild waters of romantic passion into a cool reservoir, where they can be used to irrigate what would otherwise be blasted wasteland, and make of the desert green gardens fit to dwell in.

I call it grim because the prospect of an unhappy parting, or fathering a bastard, offers small deterrence to a man whose life is so dangerous he may die any day, and doubts he will live out the year. It offers small deterrence to the fatalist who sees his life controlled by unseen forces beyond human grasp. Why resist small pleasures fate offers?

And, again, for the cynic, who sees vice ever rewarded and virtue ever punished, no promise of heavenly compensation for present pain will restrain him. He does not believe in such things. Why should the gods be fair in the next life, if they are not fair in this? The shades in Hades are nothing more than twittering bats in the gloom, and promises of Elysium are idle tales.

Conan is not fully a pagan character. He neither dies like Leonidas, nor throws himself for honor’s sake on his own sword like Cato of Utica. His graybeard years when all his strength is gone are never portrayed: for this would break the spell. He lives like Beowulf son of Ecgtheow, or Achilles son of Pelleas, but he does not die like them. For what would be the fun of that?

I do not belittle Robert E Howard’s monumental achievements, which few writers can match, or even approach. But I do see, sometimes tucked away in the nooks of relatively minor tales like this one, glimpses of a brighter world and a nobler conception than the Hyborian Age, and divinities more ancient of days than Mitra.

I have said above that Conan stories portray the pagan worldview, and my point here is that there is one part of that world Conan stories do not portray: the great sadness of the pagan, the sadness as wide as the sea. This is no criticism of Howard. If anything, it is a compliment.

For he has invented a new genre, even the poets of old never imagined: The epic tale without the tragic ending epics are wont to have.

It is an invention as American as the Cowboy story: the pagan comedy, where, instead of ending in a funeral, our sword-swinging lone ranger at the end of every episode merely rides off into the sunrise, seeking older, eastern lands, to conquer, and more jeweled thrones to trample beneath his rough sandals.