Conan: Xuthal of the Dusk

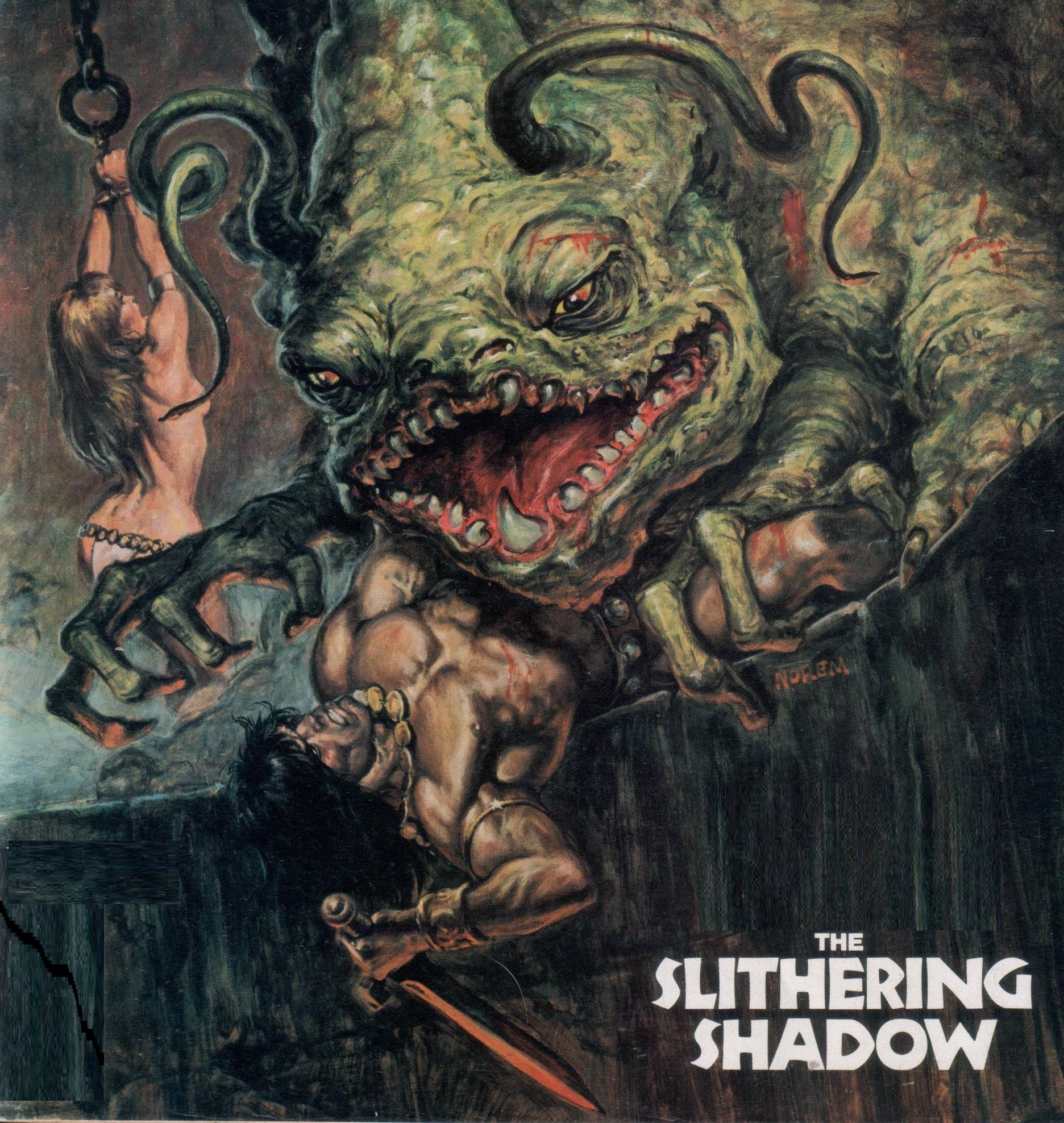

Xuthal of the Dusk is the fifth story in the Conan canon, first published in Weird Tales, September 1933, under the title The Slithering Shadow.

If this is the first Conan story you ever read, your notion of him will not be the aging but still stalwart king, tough as an old oak tree, betrayed but still fighting, nor again the daring thief who escapes from a curse-shattered tower of eldritch witchery, nor the young warlord wise in war-craft. In Xuthal of the Dusk, we finally see him in the setting, situation, and garb of the Conan of popular imagination.

I have seen reviews dismiss this tale as formulaic. It may be so, but let is also be remembered that this was one of the tales that set the formula.

The clash of varied armies, exotically armed and bright with ancient splendor, which filled half the tales, here is absent. The supernatural, which appears in all stories, here is merely monstrous without being eerie.

The callipygous harem girls, buxom wenches, nubile nymphs, and svelte lascivious sultanahs, garbed, if at all, only in begemmed bikinis, who drape their shapely limbs with studied abandon across nigh every paperback cover, and comic, and poster of Conan and all his epigones, in this yarn, finally are fully in the forefront and center stage.

The plot is in four parts. In the first chapter, we are introduced to the terror haunted city and its inmates. Here is the opening.

THE desert shimmered in the heat waves. Conan the Cimmerian stared out over the aching desolation and involuntarily drew the back of his powerful hand over his blackened lips. He stood like a bronze image in the sand, apparently impervious to the murderous sun, though his only garment was a silk loin-cloth, girdled by a wide gold-buckled belt from which hung a saber and a broad-bladed poniard. On his clean-cut limbs were evidences of scarcely healed wounds.

At his feet rested a girl, one white arm clasping his knee, against which her blond head drooped. Her white skin contrasted with his hard bronzed limbs; her short silken tunic, lownecked and sleeveless, girdled at the waist, emphasized rather than concealed her lithe figure.

Note the economy and skill with which a vivid picture is painted in a few lines: the picture of Conan in a loincloth with a shapely girl clutching his knee is, indeed, the primal, stereotypical image of Conan and all his imitators.

Conan and his lissome female companion, Natala of Brythunia, are the last survivors of an obliterated army, where Conan was serving as a mercenary, that had been driven into the southern desert to perish. Under the murderous sun, Conan gives the girl the last sip of water from the emptied canteen, and raises his sword for the mercy stroke, when he sees, mirage-like in the distant heat-shimmers, the spires, minarets, and glassy emerald walls windows of a silent city.

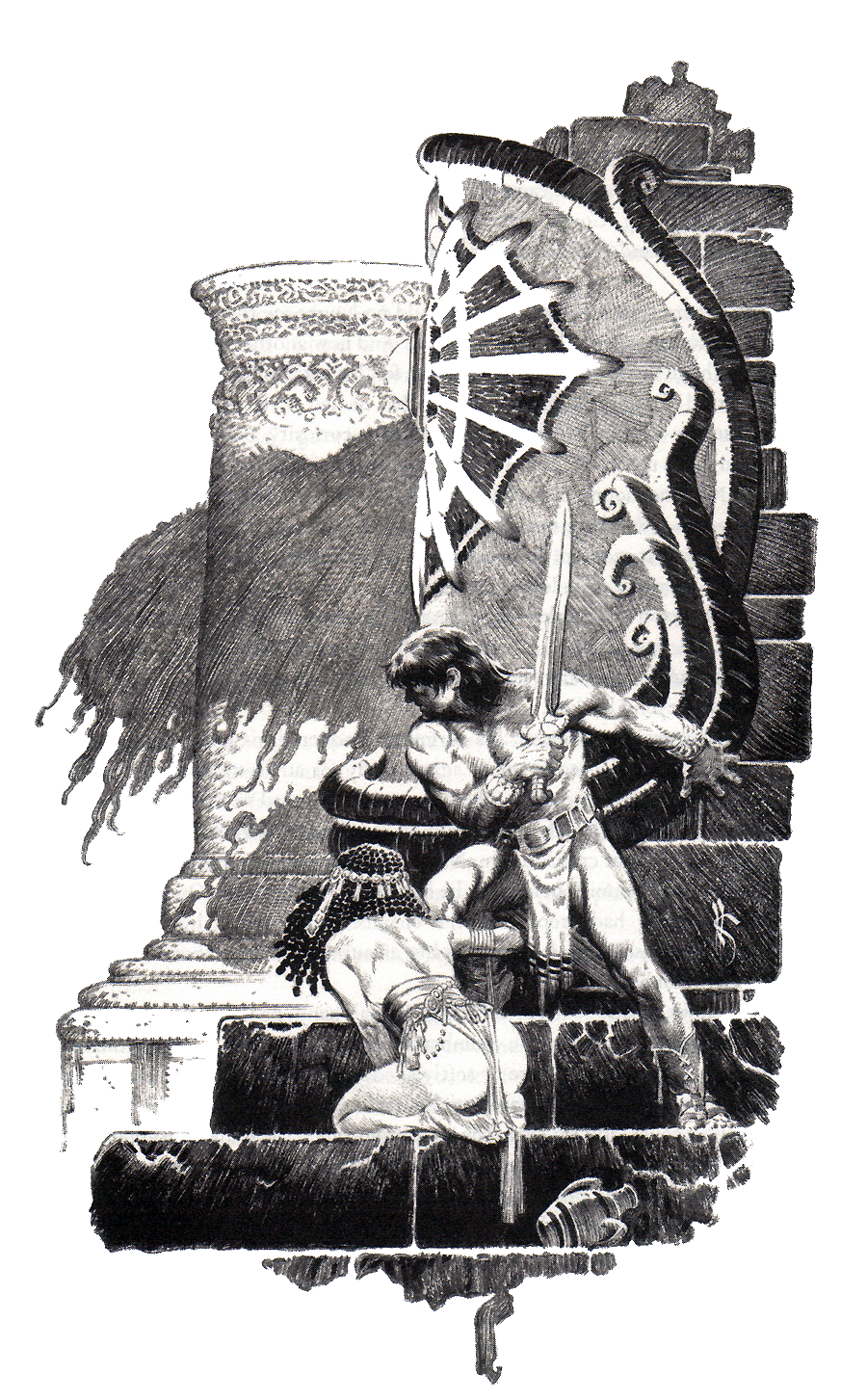

Within, all seems deserted, albeit they are beset by what seems a dead man and then by one who seems a madman. He runs off screaming, before his shouts of terror, heard in the distance, are suddenly silenced. The two find wine and fine fare set out at a feast-table where no feasters sit. A third man is seen sleeping on a silken dais: a black shadow falls over him. He vanishes, leaving only a blood stain behind.

The city turns out to be a single palace complex, held under one roof, lit by radium gems. No fields nor flocks exist outside the walls: Food is produced out of primal elements by super-science. A golden elixir serves as a panacea, restoring vitality and curing wounds. Neither trade, nor research, nor any other labor is done here. All within are addicts of opiates extracted from black lotuses grown in pits below the city. The dwellers here wake only to eat and drink and orgy before returning to windowless chambers and ecstatic dreams.

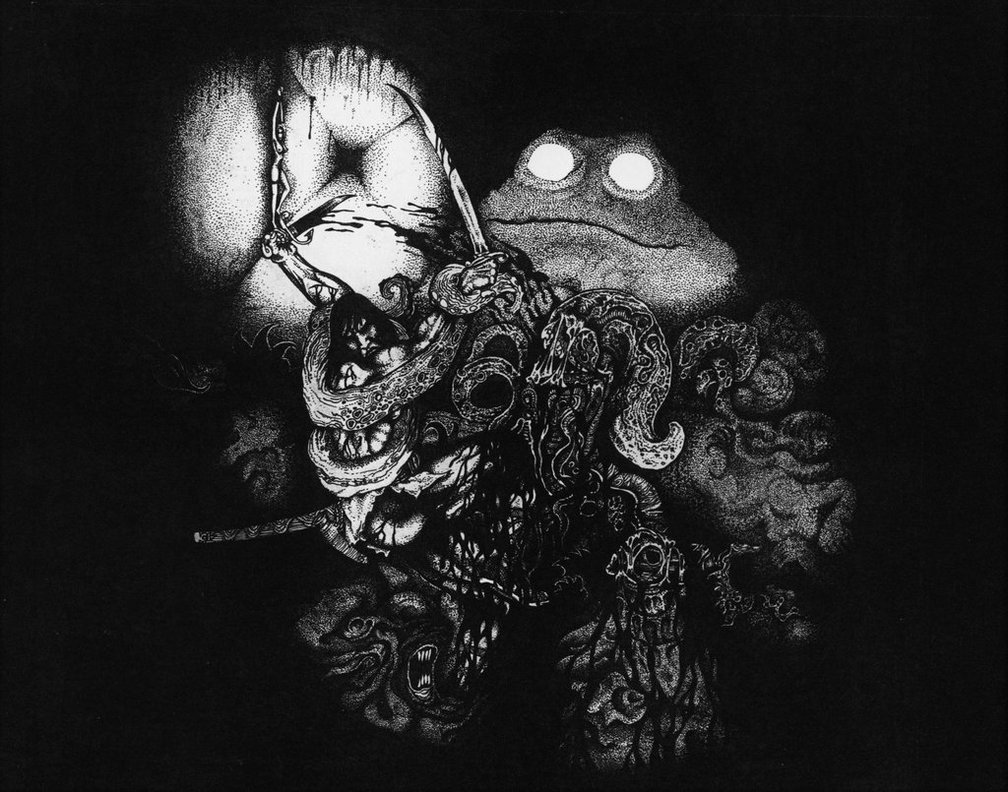

This opium-den city is haunted by a Lovecraftian devil-god named Thog, a frog-faced horror who is both shadow and substance, whose skin and tendrils and foglike shape-changing body are all burning poison, and do not seem to be able to fit into three dimensional space.

The monster sleeps in the city’s central dome, emerging at irregular intervals to consume victims found alone, and the people of Xuthal neither fight nor flee as their numbers shrink toward sure extinction. All are resigned to fate, smiling in their sleep, as they dream drugged dreams.

Conan and Natala come across a raven-haired siren of striking beauty, Thalis of Stygia. The sultry southern seductress immediately offers to make Conan king of this city, if he will become her lover; the two women likewise fall into immediate jealous ire and rivalry.

Natala’s jealousy is justified. Thalis is described as

She was tall, lithe, shaped like a goddess; clad in a narrow girdle crusted with jewels. A burnished mass of night-black hair set off the whiteness of her ivory body. Her dark eyes, shaded by long dusky lashes, were deep with sensuous mystery. Conan caught his breath at her beauty, and Natala stared with dilated eyes. The Cimmerian had never seen such a woman; her facial outline was Stygian, but she was not dusky-skinned like the Stygian women he had known; her limbs were like alabaster.

But when she spoke, in a deep rich musical voice, it was in the Stygian tongue.

Hot-blooded beauties from sword and sorcery tales waste no time on niceties: the rivalry turns murderous before the reader can turn the page. Thalis kidnaps Natala, dragging her fair captive through a secret passage, bent on sacrificing the blonde to the devil-god.

The second chapter depicts how the scantily-clad blonde beauty struggles with the scantily-clad brunette beauty, nicking her with a dirk. The brunette, in turn, is so enraged that she strips the blonde naked and flagellates her shapely body with a silken whip.

The slithering shadow arrives, kills the lovely, screaming brunette beauty, and advances upon the lovely, screaming blonde beauty. A dark, tentacle-like member slides around her white flesh to caress her bound body. If this sounds salacious to your ears, your ears do not deceive you.

The third chapter is one running fight scene, without pause. Conan finds the whole city roused against him, and slant-eyed oriental drug addicts come after him with knife and scimitar. He slaughters one and all with pantherish grace and savage abandon, casually killing their king in the process. He falls through a trap-door, and by unconvincing coincidence, lands in the lap of the slithering shadow, Thog.

The monster proceeds to strangle, crush, beat and burn him mercilessly, while the brawny barbarian, normally devastatingly deadly to foes, flails his sword against the semi-disembodied body of the brute, apparently with little effect. Frankly, Conan is curb-stomped, folded, spindled, and mutilated, and otherwise has the snot beaten out of him.

The creature, perhaps wounded, perhaps merely irked, retreats down a dark well, leaving Conan behind, bruised, battered, bleeding, three-quarters dead, and clinging to consciousness only by that savage vitality civilized men no more possess.

The fourth chapter describes how Natala nurses the half-delirious and heavily wounded Conan back to life, finding for him the golden elixir that banishes his dreadful wounds with astonishing promptitude: perhaps pulp fiction’s first healing potion. They escape the accursed and demon-haunted city, seeking an oasis and greener lands a day’s march south.

The tale ends with a bit of banter:

“Well, they’ll remember our visit long enough, I’ll wager. There are brains and guts and blood to be cleaned off the marble tiles, and if their god still lives, he carries more wounds than I. We got off light, after all: we have wine and water and a good chance of reaching a habitable country, though I look as if I’ve gone through a meatgrinder, and you have a sore—”

“It’s all your fault,” she interrupted. “If you had not looked so long and admiringly at that Stygian cat—”

“Crom and his devils!” he swore. “When the oceans drown the world, women will take time for jealousy. Devil take their conceit! Did I tell the Stygian to fall in love with me? After all, she was only human!”

Overall, a straightforward, moody, atmospheric tale of bold adventure, well-knit, well-paced, and well-told, if perhaps too spicy for modern tastes. I found several points noteworthy.

First, of the various supernatural menaces or eldritch wonders Conan has encountered in the stories read so far, Thog the Frog, in my opinion, is the least memorable. Blind pachyderm-headed aliens who fly the aether from far worlds, or vengeful sorcerers returned by their own dark arts to a hideous semblance of life, are able to make grand speeches hinting at the delirious gulfs of time and space separating man’s tiny world from the ghastly grandeur of the otherworldly powers, bent on strange business, who rule the other spheres and cycles of eternity and infinity. Here, the monster says not a word, is given no chilling backstory, and inspires no dark wonder. This monster is just a monster.

The only interesting trait about Thog is an indescribable lack of extension or location.

She (Natala) could not tell whether the being looked up at her or towered above her. She was unable to say whether the dim repulsive face blinked up at her from the shadows at her feet, or looked down at her from an immense height. But if her sight convinced her that whatever its mutable qualities, it was yet composed of solid substance…

On the other hand, it is rare to see Conan so badly beaten that he is on the brink of death. He is hardly the hero who never gets mussed. He drove away, but did not destroy, the monster. He was simply overmatched.

Second, this story is more prurient than its predecessors. I have my suspicion why.

For his first three Conan stories, no Robert E Howard scene was depicted on the cover of Weird Tales. In the fourth, a scene where a naked, nubile princess prays to an idol makes the cover, but no image of Conan. In the fifth, Howard makes the cover again, again with a nude, and again without Conan. This whipping scene is the one mentioned by Margaret Brundage (the cover artist for Weird Tales) in this excerpt from the famous Etchings & Odyssey interview:

E & O: Do you recall your most controversial cover?

Margaret Brundage: We had one issue that sold out! It was the story of a very vicious female, getting a-hold of the heroine and tying her up and beating her. Well, the public apparently thought it was flagellation, and the entire issue sold out. They could have used a couple of thousand extra.

I have it on good authority that certain Weird Tales writers, having discovered that stories containing more titillating elements were more likely to get the coveted position as cover story, added or emphasized such things. Remember the year. The Roaring Twenties were only three years gone, and neither the Hays Code for movies nor the Comics Code for comics would be seen for decades.

Did Howard go out of his way to include a nude whipping scene merely to make the cover? I cannot read the author’s mind, but I can harbor a hunch. The scene is superfluous: it interrupts our lovely murderess in mid-human sacrifice, and serves no other purpose.

Third, the portrayal of men as creatures motivated primarily by lust, and women as motivated primarily by vanity and jealousy, albeit rather cynical, is refreshing to me after the arid diet of so-called strong female characters who, alas, are neither strong, nor particularly feminine, nor, in most cases, actually characters at all, rather than sockpuppets and placeholders, and which afflict far too many in the current generation of fantasy offerings. The menfolk who orbit such so-called strong female characters are hardly worth the effort of typing this sentence to dismiss.

Here, the motivations are primal, direct, carnal, and passionate, to the point of exaggeration. I find it almost amusing how the one man who speaks to Natala falls instantly in lust with her and demands she come to his couch, whereas the one woman who speaks to Conan likewise is instantly smitten with him.

Again, Thalis was rescued from the desert sands by the degenerates of Xuthal merely for her beauty, and forced to service them in endless orgy and perversity; rather than bemoaning at her shameful life as a bordello-slave, Thalis instead vaunts at how her beauty excels that of the moon-faced, yellow-skinned girls of the East. Here, vanity outweighs pride.

Again, the sexual rivalry between Natala and Thalis is not only likewise instant, but is the prime mover for all that happens next. Like women are wont to do, Natala sizes up Thalis immediately upon meeting.

She eyed the stranger woman with suspicion and resentment. She felt small and dust-stained and insignificant before this glamorous beauty, and she could not mistake the look in the dark eyes which feasted on every detail of the bronzed giant’s physique.

Older puritans were repelled by sex, because the carnal nature pulls the soul away from more wholesome, higher, lovely, supernatural things where their attention was fixed; whereas modern puritans are repelled by masculinity and femininity, because carnal nature pulls the soul up and away from the more unwholesome, lower, ugly, unnatural things where they prefer our attention be fixed.

Opinions surely differ as to which type of puritanism is to be preferred. Such is not the discussion now. Instead, it is worthy to note that the story has not changed. Like a distant, eldritch, timeless city, the work of Robert E. Howard stands where it is. But the river of time has moved the popular opinion from one horizon to the opposite, and now the towers and ramparts are seen from another angle.

Reading older stories allow a mind to leave the cramped quarters of its own presuppositions, as see things as if through fresh eyes from fresh angles. Not that older generations, when fads were different, did not have infelicities and even obsessions of their own, that marked or even marred their art and literature.

But their fads are not the same as ours: even if their assumptions are those easily-offended moderns find offensive, nonetheless, the temptation to regard the current fads of one’s own little island of familiarity as the unquestionable laws of the world is avoided when one reads writers who stand outside the fad.

The author has Conan utter an impatient quip when Natala, although in the midst of emergency, pauses to clean herself or tend to her appearance. Likewise, moderns might be exasperated at our damsel in distress when she is portrayed as vain, that is, conscious of her good looks and her power to allure the male gaze. Moderns indulge in a somewhat willful blindness on points like this: It should not be necessary to point out that the reason why Natala is alive at all is because Conan finds her comely.

The story tells that she was saved from a slave-market by him, survived as his camp follower, and he fended off the dangers of the desert after the army whose banners Conan marched behind was utter destroyed. Conan gives her the last drop of water, and carries her in his arms to the city gates. She had better be concerned with her good looks: her life depends on them.

In his turn, he has a certain rough chivalry and rude humor I doubt one would find in a real barbarian, but which is one of Conan’s endearing traits. Beneath his savage breast, he has a heart of decency. Call it a blue collar chivalry. We can allow him the masculine privilege of scoffing at the folly of his woman, if we likewise grant her the feminine privilege of flaring up at the pigheadeness and roving-eye waywardness her man.

To be sure, all stereotypes ignore nuance, and all admit of some exceptions. Readers find stereotypes dull if used unimaginatively, or used as crutches to hide a lack of character development.

But stereotypes do not become stereotypes without a sound reason. In fiction, as in life, the stereotyped behaviors of masculine men and feminine women are based on an internal logic. When that internal logic is absent, you have persons in the drama whose actions and reactions are oddly non-human, uncanny, and awkwardly motivated, or not at all: the so-called strong female character of modern fantasy among them. She looks like a woman, usually like a very attractive one, but she is dressed and armed like a man, and her speech, motives, and actions are stiff, empty, and unconvincing.

By contrast, everything Natala and Thalis did in this tale was prompted by a motive so primal and so human that there was no mistaking it: two rivals cat-fighting tooth and nail over a mate.

Natala might be easily dismissed as a fainting and faint-hearted damsel in distress. Her role in the first two chapters, after all, is to be frightened by the eerie silences and screams of the dying, dream-haunted city, and to be abducted or menaced by murderous villainess or obscene demon-frog.

But in the final scenes, when she is no longer facing threats overpowering to her, Natala unflinchingly and quickly aids the mortally wounded Conan, and, unaided, solves the problem of how to escape the devilish city with an unconscious hero too huge for her to hold up. She is alert enough to recognize and use the golden elixir previous mentioned in passing in a conversation she had overheard.

Natala, unlike some fiercer females who people Conan tales, is unwilling to dirk to death a sleeping girl she finds when she finds the elixir. In her final words, she inquires after the fate of Thalis, and, even though the other woman tortured and would have killed her, expresses pity. Only a cynic would be unimpressed with this nobility of spirit.

I must also pause to salute Robert E. Howard in the matter of selecting names. It is a delicate art. In a fantasy story, the names are not from our world or era. They must not sound too much like ours, or be well known Bible names or Saint names, or be identifiable as typically English, Russian, or French. On the other hand, they must sound like something, and be half-familiar, like something heard in a dream, if the mood of the fantasy world, itself a half-familiar and dreamlike mood, is to be maintained.

Although a tin-eared author is allowed to do so should he wish, a lithe and lovely dancing girl from a sultry tropic shore should not be dubbed Bran Mak Morn, a surly but brave nomad warlord from the icy steppes should not be called Nyarlathotep, and the chthonic death-god of the outer pits should not be named Sfanomoë.

In the conceit behind Robert E. Howard’s Hyborian Age, the races of Conan’s world are forgotten precursors to our own.

In the 1930s intellectuals were obsessed to the point of madness with the idea that all races had personality characteristics that persisted through generations. It was one of the unspoken assumptions found frequently in the popular literature of the time.

Likewise, in our generation, our intellectuals are obsessed to the point of madness with the opposite idea: that race has no influence on personality, that all men, regardless of genetic heritage, are born as spotlessly blank slates for experience and education alone to inscribe. Which obsession is more insane is a discussion for another day.

For now, it should be enough to note that Howard bestowed names and reputations on his invented individuals of his invented tribes and nations based on what their descendants would become once entering the recorded history we readers know.

This enables him, with a neat trick, to conjure names and races that sound half familiar, so that the readers’ imagination can correctly fill in the other half without wasting words.

He plays a similar trick with the names of gods, pulling the older and more obscure names of the devils or titans from several mythologies, and assuming that the devils of one era were the gods of the prior: hence the god of Stygia is Set, who is later a devil of Egypt; or of Cimmeria is Crom, who is later a dark god of the Celts; or Ymir of Asgard, who is later a Norse titan.

Please note that like his gods, many of his place names are taken directly from myth, as if our myths are dim memories of real places. The Greeks named an imaginary realm of utter darkness Stygia; Cimmeria is a northern land never visited by the sun, a realm of endless gloom; Asgard is the Norse home of the gods.

In this case, our blue eyed blonde Natala echoes a name like Natasha or Natalia, and correctly conjures a Polish or Russian sound. Correctly, because her icy and mountainous home nation, Brythunia, houses whom I take to be Howard’s proto-Slavic peoples. Or, at least, their aristocracy is run by “boyars.”

At a guess, Stygia houses the ancestors of Egypt and Ethiopia, and, in Howard’s conception, where the magical and thaumaturgic art that later were to erect the pyramids and inscribe the walls of alabaster fanes with hieroglyphs of occult import was still strong and unforgotten. Shemites are proto-Semitic, for we see them in Conan tales mostly in roles as cunning tradesmen or fierce desert warriors. Argos houses the ancestors of all the Mediterranean peoples, such as the Phoenicians, and, obviously, Argives.

Aquilonia is proto-French, or, at least, Frankish, redolent of Aquitaine, with arms and armor from the High Middle Ages. Zingara is proto-Spain. The Cimmerians are proto-Celtic (Conan itself is an Irish name, still in use today).

Hyborians are proto-Tuetonic, as they have Norse names and place names. The Hyborians have a special place in Howard’s conception, somewhat in the spirit, perhaps, of Edward Gibbon’s theory of the Fall of Rome. The conceit is that blond northern barbarians wearing wolfpelts from harsher climes have the historic role to periodically sweep through corrupt southern lands, and reinvigorate civilization by destroying it.

(Others are far ahead of me: here is a thorough list of the place names of the Hyborian nations, and guesses as to their origins. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyborian_Age#Etymology)

Thalis sounds Greek to my ear, but the Egyptian aristocracy, at least after the conquest by Alexander the Great, bore Greek names. (Cleopatra, for example, is Greek. The names means Father’s Fame.)

Her dark eyes deep with sensuous mystery, midnight-black hair, I am reminded of how Karamenah, the Egyptian slave-girl of Fu Manchu for whom the sidekick Dr. Petrie falls, is described: “I never had seen a face so seductively lovely nor of so unusual a type. With the skin of a perfect blonde, she had eyes and lashes as black as a Creole’s, which, together with her full red lips, told me that this beautiful stranger, whose touch had so startled me, was not a child of our northern shores.”

As for the city of Xuthal, the name reminds one of the pleasure dome of Xanadu, and sounds sufficiently non-Anglosaxon to conjure the bejeweled and pagan pagodas of the golden East. The mention of Fu Manchu is also apt here: for in addition to negative stereotypes of greed or superstition a theory of racial personalities might ascribe to Shemites or Stygians, this story indulges in positive stereotype as well. The tale takes it as unremarkable that the Far East of prehistory, from which the long forgotten founders of Xuthal hailed, were master scientists of superhuman brilliance. They were a veritable race of Fu Manchus, but marred by oriental decadence.

Stereotype or not, in the 1930s, opium dens were still centered in Chinatown, and had mostly oriental patrons, or sailors who had absorbed the habit in the Far East. This was decade upon decade before beatniks or stoners or potheads were a regular sight on college campuses, or sleeping in pools of their own filth in the gutters and parks of San Francisco. The idea of an entire city of opium addicts was still a fantasy then. To any man of that time, it would be natural to people such a city with the Chinese, or their ancestors, particularly if scholars or scientists were the founders.

That a city of drug addicts is gorgeous and clean is fabulously improbable and unrealistic, but it is thematically inevitable. If the point of Conan stories is to show civilization to be a golden cage, the cage bars must be gold. Xuthal is a city of opium dreams: and opium dreams are fair, if insubstantial. Like the drug itself, the addict may be consumed by the formless and obscene shadow dwelling in the sacred central dome of his life at any moment.

I cannot end without commenting on how closely the city of Xuthal resembles two other cities: first, it resembles the equally self-contained walled and roofed city of Xuchotil from Red Nails, Howard’s last published Conan story, albeit there, the race was addicted to bloodshed, not opium, and were distinctly Aztec in name and theme.

Second, odd as this sounds, Xuthal is parallel to the self contained cities of the Airlords of Han from the first Buck Rogers story, ARMAGEDDON 2419 A.D. Inside their windowless towers, the Han led lives of amorous dissipation, as all their food was artificially and automatically produced in underground vaults.

The theme central to all Conan tales is the savage decency of the young barbaric tribes compared to the overly complex decay of old civilizations. In Xuthal, we see the clearest example and starkest contrast yet: The civilized folk are slaves to libido, and fodder for a false god. When thwarted, Thalis reacts with sadistic cruelty, and the nameless Xuthali, when frightened, runs screaming headlong to his doom. Conan’s grim self-control is obvious in contrast, and, despite his animal passions and wild nature, he will not betray his current girl for a fairer one.

The most chilling part of the portrayal of the doomed city is the casual acceptance voiced by Thalis. She, like the Easterners, are fatalists. It is vain to run from fate. Who can escape the gods?

In a cold and aloof display of sophistry, Thalis dismisses the idea of objecting to being eaten by Thog, on the grounds that he is, after all, a god: and what is the difference between being hauled off as a human sacrifice by the priests, or having the god emerge from his temple to feed himself?

Conan scoffs at the theological nicety, saying, “by Crom, I’d like to see a priest try to drag a Cimmerian to the altar! There’d be blood spilt, but not as the priest intended!”

Thalis answers by calling him a barbarian. She then says that the Xuthali are very advanced in one art: hedonism.

“… They live only for sensual joys. Dreaming or waking, their lives are filled with exotic ecstasies, beyond the ken of ordinary men.”

“Damned degenerates!” growled Conan.

“It is all in the point of view,” smiled Thalis lazily.

And, in that one curt line, we see a condemnation of the doctrines poisoning the modern world more damning than a dozen sermons or ethical theories could muster.

Robert E. Howard, even in minor works, or formulaic adventure fare, wields a pen sharp enough to cut to the heart of man.