Conan: Pool of the Black One

Into the west, unknown of man,

Ships have sailed since the world began.

Read, if you dare, what Skelos wrote,

With dead hands fumbling his silken coat;

And follow the ships through the wind-blown wrack—

Follow the ships that come not back.

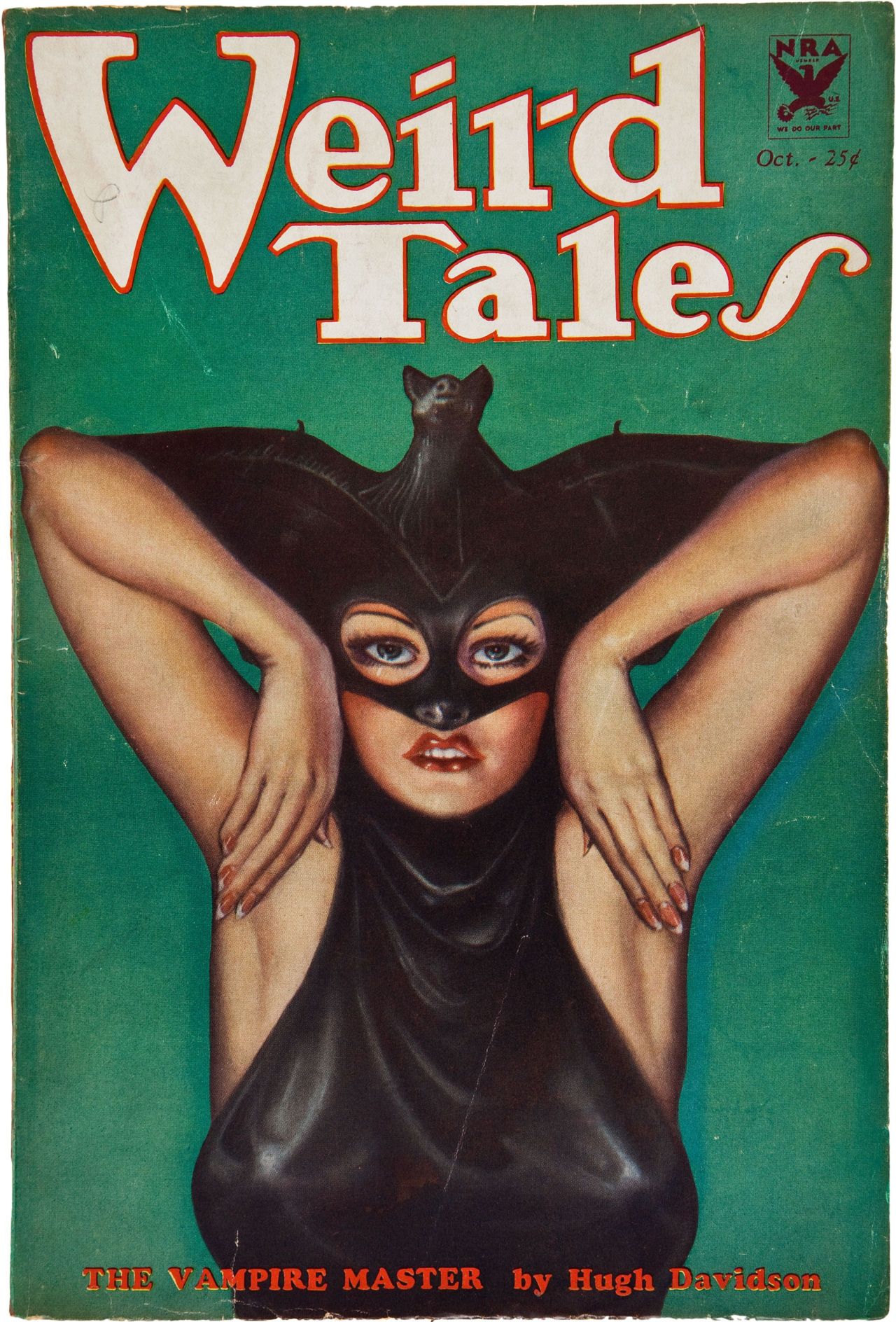

With these eerie, evocative words opens Pool of the Black One, the sixth published Conan tale, first published in Weird Tales, October 1933. Conan did not make the cover, but this image is famous among aficionados of weird illustration, so I hasten to post it here:

I fear that, as I go in publication order through the Conan canon of Robert E. Howard’s Hyborian Age stories, if I continue to praise each tale as brilliant and original, the reader might begin to suspect that I gush over everything flowing from Howard’s pen uncritically.

But, alas, Howard’s writing continues to be brilliant and original, and my critical eye sees little to criticize. To be sure, there are recurring themes and tropes that repeat from tale to tale, but rather than seeming rote or unoriginal, they gather momentum and weigh, in just the same way, in comedy, if done right, a running joke gets funnier each time it is revisited.

Here, Howard’s theme, central to the character of Conan, of contrasting barbarism with civilization, is almost too stark. With Pool of the Black One, Conan is not the daring young rogue, bold veteran, mercenary captain, weary king beset by treason, or thrown from his throne, which we saw in prior tales. Instead, he is a freebooter, a buccaneer, a corsair and cutthroat.

Conan here is Douglas Fairbanks or Errol Flynn, but only if the Black Pirate or Captain Blood were a cynically ruthless killer and womanizer, facing Lovecraftian horrors. A jovial version of Conan, a man of enormous mirth, is a side of his character not before seen: as is his darker side as a treacherous, scheming villain.

Nor is his pirate career a surprise. In the opening prologue of his first appearance, Conan is called “a thief, a reaver, a slayer.” A reaver is a robber in general, but the word is often a synonym for sea-pirate.

So it is not the corruption of overly delicate courtiers with bejeweled daggers our bronze-skinned savage faces this time, but a wolfpack of bullies and brawlers armed with cutlass and belaying pin, themselves only a hair lifted up from the barbarism of his origins.

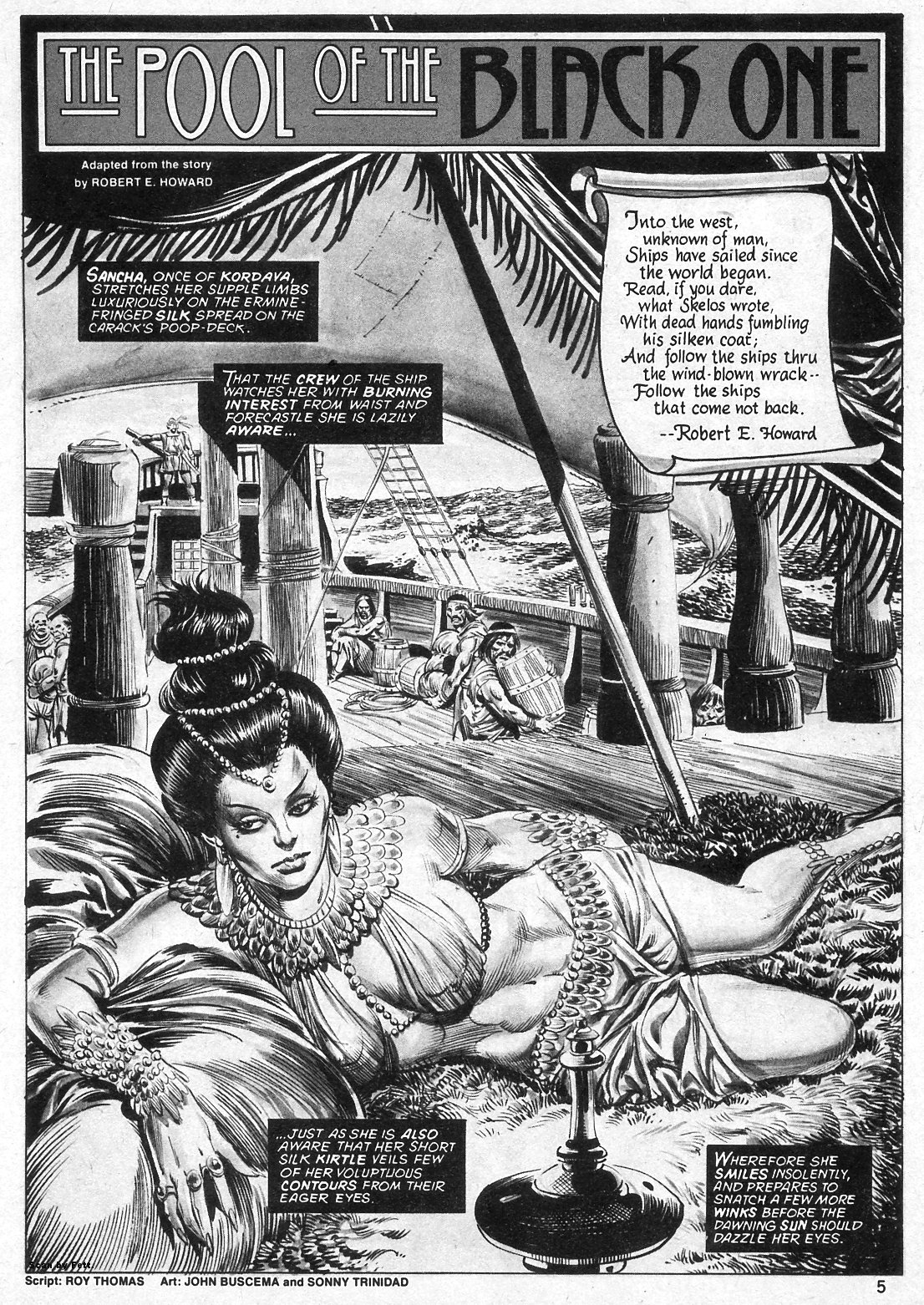

The salaciousness we saw in the last two tales is here, once again, displayed in all its spicy allure. The story opens with a voluptuous senorita, yawning daintily sunbathing her supple body on the poopdeck of a pirate ship, luxuriating in the burning rays of the sun and the burning gazes of the rowdy crew.

The tale is divvied into three parts. In the first, Conan climbs dripping from the sea onto a pirate galleon, into the wondering (and lust-filled) gaze of Sancha of Kordava. The gloomy captain Zaporavo arrives, scowling. He is described memorably in a few well chosen words:

He was a tall man, tall as Conan, though of leaner build. Framed in his steel morion his face was dark, saturnine and hawk-like, wherefore men called him the Hawk. His armor and garments were rich and ornate, after the fashion of a Zingaran grandee. His hand was never far from his sword-hilt.

If the reader mistakes our Zingarans for a Spaniards, he is not far wrong. Zaporavo accepts Conan’s fealty as a new deckhand, rather than pitch him back to the sharks, but, in a rare moment of foreshadowing, we are told “… and doing so, lost his ship, his command, his girl, and his life.”

After killing a man in a brawl, Conan wins the camaraderie of the roughnecks, and the affection, if it can be called that, of Sancha, the captain’s doxy. For Conan’s part, his winning over the hearts of the crew is deliberate, as he means from the first to kill Zaporava, and take his place.

The ship sails out of the sight of shore, into unknown waters where there are no ships to plunder and no cities to sack. What Captain Zaporava seeks is unclear. In strange and striking words, we are told:

[He] pored over ancient charts and time-yellowed maps, reading in tomes that were crumbling masses of worm-eaten parchment. At times he talked to Sancha, wildly it seemed to her, of lost continents, and fabulous isles dreaming unguessed amidst the blue foam of nameless gulfs, where horned dragons guarded treasures gathered by pre-human kings, long, long ago.

The ship makes landfall at a green, spice-scented isle. Once ashore, the crew eat a fruit with sinister soporific properties, and immediately fall asleep on the strand. The captain goes off by himself into the forested hills inland, seeking primordial secrets, but is followed by Conan, who sees his opportunity for murder.

The girl, pouting and sullen at being left behind, strips herself naked to swim to shore, and seeks Conan. While she is alone and lost, the unnatural horror lurking on the island comes upon her suddenly.

In the second part, Conan besets Zaporava and kills him. He then sees one of the monstrous manlike beings inhabiting the island, jet-black and speechless giants with gold eyes and fingers tipped with talons, and follows the apparition to a green citadel of Lovecraftean towers.

Lovecraftian they are, because, like Lovecraft, Howard quails at describing the indescribable, instead taking refuge in rather conclusory words:

He realised uneasily that no ordinary human beings could have built them. There was symmetry about their architecture, and system, but it was a mad symmetry, a system alien to human sanity.

How one deduces mental states from symmetries, I leave to students of modern art and modern architecture to tell.

Sneaking within, Conan sees the obscene ritual whereby the youngest crewman is drowned and petrified in an alchemic pool, his whole body shrunk into a figurine, much as a headhunter shrinks a head.

In the third part, Conan seeks to rescue the girl and the crew which apparently are now his, before any follow the young sailor into the ghastly pool. The battle between pirate and giant is savage and grotesque, as the crewmen are half-drunk, still woozy from the effects of the soporific fruit they ate, and as the giants fight with bare hands, making no outcry. With terrific losses, the men prevail, the giants are slain to the last.

The final giant, their king, utters a terrific outcry, and leaps into the alchemic pool, the waters whereof then come to life, rise up, and set off pursuing the pirate crew like a titanic snake. All run toward the ship, but not all make it.

The tale ends as if with a flourish of Erich Korngold trumpets in an Errol Flynn flick, with our brawny barbarian, now ruthless Pirate captain, sailing off into the Eastern sunrise, eager for jeweled thrones to trample beneath his sandaled feet.

“What now?” faltered the girl.

“The plunder of the seas!” he laughed. “A paltry crew, and that chewed and clawed to pieces, but they can work the ship, and crews can always be found. Come here, girl, and give me a kiss.”

“A kiss?” she cried hysterically. “You think of kisses at a time like this?”

His laughter boomed above the snap and thunder of the sails, as he caught her up off her feet in the crook of one mighty arm, and smacked her red lips with resounding relish.

“I think of Life!” he roared. “The dead are dead, and what has passed is done! I have a ship and a fighting crew and a girl with lips like wine, and that’s all I ever asked. Lick your wounds, bullies, and break out a cask of ale. You’re going to work ship as she never was worked before. Dance and sing while you buckle to it, damn you! To the devil with empty seas! We’re bound for waters where the seaports are fat, and the merchant ships are crammed with plunder!”

A few observations as to setting, mood, the theme, the characters, and the spirit.

There is an immense usefulness to setting a tale in lands off the edge of the map or beyond the reach of the calendar, and that it that niggling details like technology levels need not hinder the imagination. The ship here is described as a carack, that is, a type of three-masted merchant galleon from the Fifteenth Century.

While one might have expected an Athenian trireme or Roman galley in our ancient world, the Hyborian Age, by being prehistory, is allowed to range anywhere between the Late Middle Ages and the Early Stone Age in technology, throwing in the occasional radium gem or dinosaur from years even farther afield for flavor.

To be sure, there have been pirates from prehistory, from Chinese seas to Arabic to Norwegian, but those are not the pirates we want. When an author mentions poop-decks and freebooters from places called Tortage or Kordava (Tortuga and Cordova), and when the rowdy crewmen are, just as should be, dressed as pirates from central casting: ” half naked, their gaudy silk garments splashed with tar, jewels glinting in ear-rings and dagger-hilts” then it is safe to conclude that the author’s intent is to conjure up of all the atmosphere and furniture of TREASURE ISLAND, namely “schooners, islands, and maroons, and buccaneers and buried gold, and all the old romance, retold, exactly in the ancient way…”

At to the mood of the work, it is, as promised, notably savage, and appallingly cynical. I recently discovered a most useful word: picaresque, meaning ‘of rogues or rascals’. It also means a genre of fiction dealing with the episodic adventures of a roguish protagonist, usually of low standing, stumbling into adventures among the higher classes, all of whom are rogues worse than he, and he relies on his wits and a little dishonesty to get by. For example, the Cugal the Clever stories of Jack Vance in his Dying Earth settings are pure quill picaresque.

I suspect the main appeal for most readers is the pleasing daydream of retaliating against social superiors, and seeing them unmasked as despicable.

But a second appeal is just the desire to scratch the itch of cynicism, to take a vacation in a world where everyone’s moral compass is more broken than your own, so there is no fretting about complex ethical riddles, no worry about the duties, or doing right, and no high standard pristine as a virgin, to which to aspire.

Grim detective stories where the cops are as bad as the crooks, or prurient vampire stories where the blood-suckers only kill boring, ugly, or annoying people, allow the reader to sip the heady wine of anarchy for an afternoon, if only in his imagination, and dwell in a twilight where the simple rule always is kill or be killed, and take the buxom girl as your trophy after.

In keeping with the picaresque tone of the tale, we at times have wry observations about the folly of men:

The outlaws who infested the Baracha Islands … raided the shipping, and harried the coast towns, just as the Zingaran buccaneers did, but these dignified their profession by calling themselves freebooters, while they dubbed the Barachans pirates.

They were neither the first nor the last to gild the name of thief.

In that sense, Pool of the Black One is more picaresque than most Conan tales. Usually he displays a rough chivalry, and a sense of honor. Not here. When he sees the captain venturing alone inland, he glides after a stalking panther. His reasoning is given in full

Conan did not underrate his dominance of the crew. But he had not gained the right, through battle and foray, to challenge the captain to a duel to the death. In these empty seas there had been no opportunity for him to prove himself according to Freebooter law. The crew would stand solidly against him if he attacked the chieftain openly. But he knew that if he killed Zaporavo without their knowledge, the leaderless crew would not be likely to be swayed by loyalty to a dead man. In such wolf-packs only the living counted.

One has to wonder about this Freebooter law. Insubordination and murder get the thumbs up if you do it on the sly. I have it on good authority that the Pirate’s Code is more what you call ‘guidelines’ than actual rules.

As for chivalry and honor, well, not so much.

In the midst of the glade Zaporavo, sensing pursuit, turned, hand on hilt. The buccaneer swore. “Dog, why do you follow me?”

“Are you mad, to ask?” laughed Conan, coming swiftly toward his erstwhile chief. His lips smiled, and in his blue eyes danced a wild gleam.

Zaporavo ripped out his sword with a black curse, and steel clashed against steel as Conan came in recklessly and wide open, his blade singing a wheel of blue flame about his head.

The theme of the innate superiority of barbarism over civilization is on full display, and gilded, in this scene. Savages are automatically better fighters, no matter any difference in training.

Zaporavo was the veteran of a thousand fights by sea and by land. There was no man in the world more deeply and thoroughly versed than he in the lore of swordcraft. But he had never been pitted against a blade wielded by thews bred in the wild lands beyond the borders of civilization. Against his fighting-craft was matched blinding speed and strength impossible to a civilized man.

Conan’s manner of fighting was unorthodox, but instinctive and natural as that of a timber wolf. The intricacies of the sword were as useless against his primitive fury as a human boxer’s skill against the onslaughts of a panther.

As for me, I feel sorry for the man who is the most well-versed and skilled swordsman in the whole world being bested by a quick and strong adversary who is just born better than he. Hardly seems fair.

My own limited experience as a fencer gives a ripe and loud Bronx Cheer to the idea that natural talent can overwhelm trained skill with a blade. I have fought men stronger and faster than I, but less skilled, and have fought men slighter and slower than I, but more skilled. The victories are not just occasionally or even mostly to the more skilled swordsman, but inevitably. My stronger but unskilled foe could not land a single touch on me, no, not one. My weaker but more highly skilled foe did not let me land a single touch on him, no, not one.

On the other hand, if the reader is not willing to accept, as a given, that naked aborigines, scratching themselves with sticks, living in mud huts, drinking from mud puddles, and eating mud-worms are not stronger and faster than the Olympic Athletes or US Marines formed by training grounds or bootcamps of civilization, such a reader simply is not entering into the daydream of the noble savage, and into the spirit of a Conan story.

It is as stubborn as saying there is no such planet as Kripton, or no such thing as an Amazon, or that no orphaned millionaire fights crime in secret by dressing as a bat. The one unreal conceit to be granted the author is the ticket price for entering any fiction story. Anyone unwilling to pay is left outside, and will never get what this genre of stories are about, or what their appeal is.

As to the characters, we should observe how well Howard depicts them with a masterful brevity. Zaporavo, for example, has to be killed without prompting reader sympathy, even though he saved Conan from shark infested waters, gave him berth and board, and did him no harm.

The skilled storyteller’s trick to kill sympathy is to make the character a creep. Here, Zaporavo is a Captain Ahab:

“… engrossed with his broodings, which had become blacker and grimmer as the years crawled by, and with his vague grandiose dreams; and with the girl whose possession was a bitter pleasure, just as all his pleasures were.”

To make the man worse than Ahab, we see how he treats his girl:

“He never gave any explanation for his commands; so she never knew his reason, unless it was the lurking devil in him that frequently made him hurt her without cause.”

You see? If he is sadistic to the half-clad and dainty red-lipped nymph we saw in the first paragraph sunning her lithesome and shapely limbs, even I now want him dead.

The point here is that in a picaresque tale, the cops are not more law-abiding than the crooks, nor are the nobles more noble or less vulgar than the vulgar. There conflict is never between a moral white and black, it is between a moral lighter gray and darker gray.

His girl is as vivid as is Zaporavo. She is both the damsel in distress, but also the fulcrum of an odd love triangle where there seems to be no love involved between the captain, herself, and Conan.

Not unexpectedly for a Howard story, despite being but a curvaceous glamour girl, Sancha also plays a crucial role in saving everyone’s life, by smuggling arms to captive sailors, and rousing from fumes of drugged slumber to stand to their defense.

She is a daughter of nobility, abducted into a life as her cruel captain’s doxy, and the author, in words of appalling cynicism, notes

She, who had been the spoiled and petted daughter of the Duke of Kordava, learned what it was to be a buccaneer’s plaything, and because she was supple enough to bend without breaking, she lived where other women had died, and because she was young and vibrant with life, she came to find pleasure in the existence.

This is, in truth, as horrible as any fate as can befall a woman. Isabella, princess of Gallicia, in the epic ORLANDO FURIOSO, tricks the pagan knight Rodomont into killing her before he can impose on her the same life of unpaid and loveless sexual servitude Sancha here accepts and enjoys. This is the difference between pagan and Christian literature, as well as between high fantasy and sword-and-sorcery.

Sword and sorcery, I suggest, has a low-class, blue-collar vibe to it. The common man might like to hear about common decency and common sense in their heroes, but any pretense of noble ideals they will often regard with a smirk, since they have seen too many nobles.

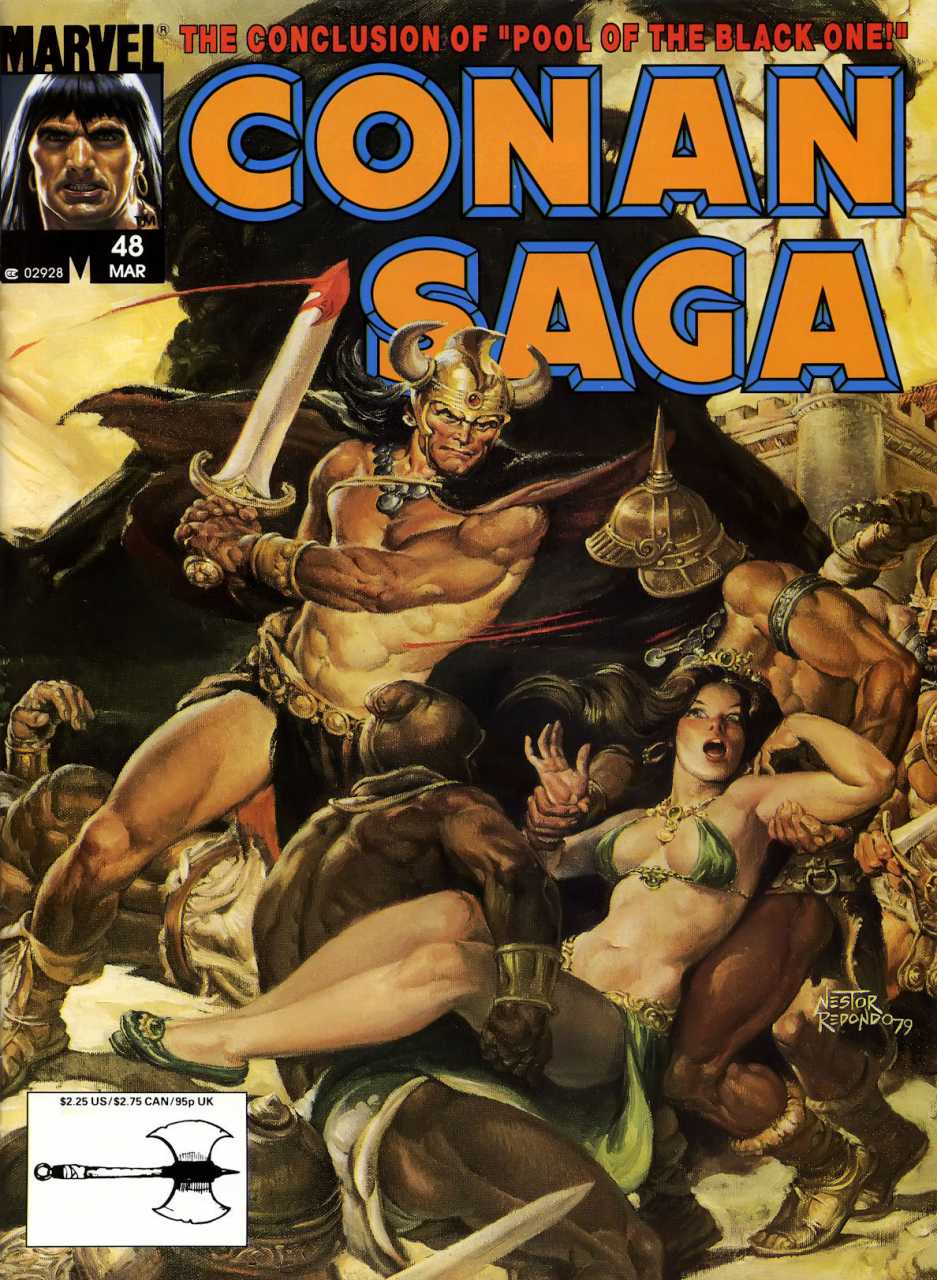

Conan himself displays, as said above, a jovial and magnanimous side of him we have not seen before: grinning, laughing, large-hearted, generous in gambling, filled with joy. This is a marked contrast to the oft-seen Frank Frazetta image of him scowling or brooding. As befits a pirate yarn, he here acts the part of a dashing swashbuckler.

The dullest was struck by the contrast between the harsh, taciturn, gloomy commander, and the pirate whose laugh was gusty and ready, who roared ribald songs in a dozen languages, guzzled ale like a toper, and – apparently—had no thought for the morrow.

This laughing nature is given as the main reason the crewmen, and the sultry siren, switch loyalties from the captain to him. He is just a great guy to be around. And, yes, he may save you from a haunted island filled with murderous mutes who want to feed you into an unholy petrification pool.

Which brings us, finally, to reflect upon the spirit of the story. What is it saying? What is the message here?

I submit that, despite being cynical as all get out, and grim, and bloody, and more than a little sarcastic toward all things chaste and noble, Conan tales in particular, and sword and sorcery in general, are a world away from the empty-eyed skull-grinning monstrosities we see in stories that are nihilist.

A picaresque story can be as cynical as it wants about men, but it has to admire common bravery, camaraderie, and other good things, or else there is no story. The point of a picaresque story is not to say that good and evil men are all the same and interchangeable, and nothing matters. Like a satire, a picaresque cannot make its point if the contrast with the opposite is not clear. It is no fun poking fun at a pompous high-class snob for being a rogue, unless the rogue if only in a small way, is not better than he. This is why Disney’s Aladdin gives the bread he steals to starving children as penniless as he: otherwise the theft is merely theft, and he is merely a villain.

In a nihilist story, evil is merely a point of view no better and no worse than any other. But in a Conan story, in this story, evil is obscene.

Here is the scene where the Zingaran cabin boy is made to dance to the silent influence of pan pipes Conan cannot hear.

The Zingaran youth… quivered and writhed as if in agony; a regularity became evident in the twitching of his limbs, which quickly became rhythmic. The twitching became a violent jerking, the jerking regular movements. The youth began to dance, as cobras dance by compulsion to the tune of the faquir’s fife.

There was naught of zest or joyful abandon in that dance. There was, indeed, abandon that was awful to see, but it was not joyful. It was as if the mute tune of the pipes grasped the boy’s inmost soul with salacious fingers and with brutal torture wrung from it every involuntary expression of secret passion.

It was a convulsion of obscenity, a spasm of lasciviousness – an exudation of secret hungers framed by compulsion: desire without pleasure, pain mated awfully to lust. It was like watching a soul stripped naked, and all its dark and unmentionable secrets laid bare.

Conan is the toughest hard boiled egg in the Hyborian world, but even he is shocked.

Conan glared frozen with repulsion and shaken with nausea. Himself as cleanly elemental as a timber wolf, he was yet not ignorant of the perverse secrets of rotting civilizations. He had roamed the cities of Zamora, and known the women of Shadizar the Wicked. But he sensed here a cosmic vileness transcending mere human degeneracy—a perverse branch on the tree of Life, developed along lines outside human comprehension. It was not at the agonized contortions and posturing of the wretched boy that he was shocked, but at the cosmic obscenity of these beings which could drag to light the abysmal secrets that sleep in the unfathomed darkness of the human soul, and find pleasure in the brazen flaunting of such things as should not be hinted at, even in restless nightmares.

Now, in the world where the heroes are pirates and the gods are prehistoric devils, what is the other option, aside from the cosmic obscenity outside human comprehension?

Like Lovecraft, those who do not believe in cosmic goodness must be satisfied, it at all, with the small and human good things that can be found in the here and now. A Lovecraft character might seek the comfort in life in cats and New England hamlets, and all things old and familiar, or in chasing exotic dreams; Conan has tastes just as plain, but far more violent and vivid.

That is the point of Conan’s curtain line. Rare is the boy reader so cynical or so saintly that the roaring call of the pirate’s life , with a voluptuous doxy in one arm, sword in hand, and a sound ship and swift beneath the foot, holds no allure, and the promise of a fierce fight ahead, bright steel, red blood, yellow gold, and dark wine.

If we stand in amazement that Conan stories are still being read and discussed eighty five years after first seeing print, we should note that such stories tend to get more popular when society is facing temblors of decay and chaos, as we did in the 1940s, and again, during his revival as a Marvel Comics character in the 1970s. At such times, the noble aspirations of the elites seem a little hard to swallow, or, as in our current day, when our elite are perverse and strident and moralistic and disgusting, a little bit of blood and thunder, a rank of foes plain to see and a trusty sword to cut a straight path through them, is much to be desired.

These tale perhaps appeared in humble pumps, cheaply printed for humble audiences, but consider: Conan would have been forgotten with his contemporaries long ago, if his tales did not touch something deep and primitive and primal in the human heart. Practitioners of moderns arts cannot boast as much.