Conan and the Gods

In May of 1934, Robert E Howard’s Queen of the Black Coast was published in Weird Tales. This column is the second to review the story. The first part is here.

Many a fan, this one included, calls Queen of the Black Coast the finest of the Conan stories, in part because of its legendary scope, in part because of its lurid romance, it passages of lyrical poetry, its vivid and bloody battle-scenes, the sense of mystery and adventure, the chilling eldritch visions of ancient eons and shades of the dead, the Viking funeral at the end.

The writing excels on three levels: first, striking characterization gives life to an intimate and tragic romance; second, lyrical world-building conjures a vision of a lost age, cruel but not without its savage beauties; third, a deep and even grim theme dignifies what would otherwise be a mere boy’s adventure tale with adumbration of deep time and an almost Norse melancholy touching the brevity of life, the indifference of the gods.

Let us look at each in turn.

The romance is striking thanks to the vibrant portrayal of a love interest worthy of the bold barbarian of Cimmeria, namely,Belît, eponymous the Queen of the Black Coast.

We hear much meaningless codswallop about what are called strong female characters in genre fiction this days. Usually this refers to wooden heroines indistinguishable in word and deed from heroes, hence utter failures at the art of characterization. The absurdity of portraying such women as mythical amazons, physically strong as men, is now commonplace.

The question of why anyone, either as reader or writer, regards such portrayals as anything other than a gross insult to everything female and feminine, is a question best left to abnormal psychology to answer. In the meanwhile, it is enough to notice that when strong female characters are actually portrayed as strong in a feminine way, hence will have character, the strength involved need not be physical.

Ponder the following exchange between the two lovers as they sail down a dark river toward their fate:

“Mystery and terror are about us, Conan, and we glide into the realm of horror and death,” she said. “Are you afraid?”

A shrug of his mailed shoulders was his only answer.

“I am not afraid either,” she said meditatively. “I was never afraid. I have looked into the naked fangs of Death too often…”

And, one must hasten to add that the text bears out this boast: at no point in the tale, do we see this majestic, wicked pirate queen hesitate nor flinch nor cower.

To the contrary, her downfall is due to a lack of that reasonable fear whose cold hand might calm the cupidity of raiders seeking to loot a haunted city surrounded by rumors of terror.

A person of ordinary caution, I suspect, would have re-embarked her ship and fled not long after landing, when a grotesque figure atop a monumental column in the dead city by the poisoned river was seen not to be the statue she first thought, but instead stirred to life, spread its naked wings of membrane against the blood red moon, and soared aloft. Instead, she neither posts guards to watch the ship, nor hears the sounds of the winged ape’s mischief, because her lust for gold and gems distracts her.

As she says, mystery and terror are indeed about them.

Here are glimpses of the world of Conan, as seen from the deck of master Tito’s merchant ship on which he serve before he meeting the black pirates:

They sighted the coast of Shem–long rolling meadowlands with the white crowns of the towers of cities in the distance, and horsemen with blue-black beards and hooked noses, who sat their steeds along the shore and eyed the galley with suspicion. She did not put in; there was scant profit in trade with the sons of Shem.

Nor did master Tito pull into the broad bay where the Styx river emptied its gigantic flood into the ocean, and the massive black castles of Khemi loomed over the blue waters. Ships did not put unasked into this port, where dusky sorcerers wove awful spells in the murk of sacrificial smoke mounting eternally from blood-stained altars where naked women screamed, and where Set, the Old Serpent, arch-demon of the Hyborians but god of the Stygians, was said to writhe his shining coils among his worshippers.

Master Tito gave that dreamy glass-floored bay a wide berth, even when a serpent-prowed gondola shot from behind a castellated point of land, and naked dusky women, with great red blossoms in their hair, stood and called to his sailors, and posed and postured brazenly.

Now no more shining towers rose inland….

… So they beat southward, and master Tito began to look for the high-walled villages of the black people. But they found only smoking ruins on the shore of a bay, littered with naked black bodies.

In four short paragraphs, the reader is invited to see the soul and substance of Conan’s world, and how starkly it differs from the fields we know. Fierce warriors ahorse glare with suspicion; magicians and evil priests burn human sacrifices; exotic harlots tempt; robbers and raiders leave death and ruin where they pass.

(If this reminds the readers of the tally of character classes one can play in Dungeons and Dragons, fighting man and magic user, cleric and thief, there is no coincidence: Gary Gygax freely admitted his main inspiration, or one of them, were these Howard tales.)

More to the point, schoolboys reading such offerings in the 1930’s were no doubt vaguely aware of some lapse or absence in their lives. This passage shows that Robert E Howard keenly felt the same lapse, and knew what was missing from the modern world: savage warlords, sorcerers and slant-eyed mages, harem girls, golden towers gleaming like dreams far off in the sunset beams, shining swords, haunted pyramids, deadly jungles, and half-naked pirate queens as fair as pagan goddesses: everyone one was most unlikely to find while waiting for a streetcar in the crowded lanes of a dirty modern metropolis.

While on the level of the world-building there is certainly a nostalgia, as there is in most stories taking place in a past that never was, for the world view that predates the Christian world, and the scientific investigation of nature which sprang from the belief in a rational and monotheistic creator-god, rather than whimsical myriads of gods.

But the tale is as stern and grim as a Wagner opera, for Howard’s prehistoric civilizations are not the happy realms of a golden age. It is an age of wolves and wolflike men, an age of cold iron, an age before revelations of bright heaven, and all men knew or dreamed of gods was twilight, half-seen, dark.

The theme is a dark one for a story where the bright flame of erotic love is midmost centerstage, and the contrast is striking: it is like seeing a single island of joy in an endless ocean of desolation.

The setting of the central act is the ruined city of a preadamite superhuman race, who degenerate from superhuman heights through ages of devolution to the subhuman, until only one apelike hunchback remains.

The writer emphasizes that these beings were never humans, were not even primates, but came from another branch of evolution entirely, and were old before man’s first primitive ancestor climbed to the shores of oozy primal seas. This means the winged beings were not a mere age or epoch older than mankind, not a matter of millions or tens of millions of years, but rather were older by eras or eons, that is, hundreds of millions of years, or even half a billion.

The poisonous scent of an intoxicating orchid renders Conan numb and helpless, but also grants him a vision of the eon-spanning downfall of the godlike primal race, who, for reasons unknown, refuse to leave their ancient dwelling even after the change of clime and geography render the environs toxic to them, and the slow poisons accumulate throughout their generations.

This image of unfathomable time is one that has haunted the modern mind since the time of Darwin, and the geological discoveries of his generation. The geocentric cosmos created a mere sixty generations before Christ, peopled by humans as of the end of the first week, indeed from our modern view seems cozy and small. We are used to astronomical reaches of void surrounding our tiny globe, and an abyss of prehistory so vast the one is tempted to turn to oriental measurements of yugas and kalpas to express it.

Conan’s cosmos, despite being set during the forgotten age after the sinking of Atlantis, reaches to the gloomy magnitudes of deep time and endless space, and hence is entirely modern in that regard: it is set in the cosmos as Einstein sees it, not Copernicus nor Ptolemy.

The selection of the setting and the antagonist serves to drive this point home:

The winged ape is the last of his species. Save for a sadistic trick of transforming men into hyenas, all their occult lore, and other arts and sciences, are vanished. Conan, it must be remembered, occupies the continent fated to be riven by future catastrophes vast as the sinking of Atlantis before the modern coastlines and mountains appear, or the Mediterranean is formed. To us, Conan’s world stands as his world to that of the winged beings of the nameless city. Nothing will withstand the dark decrees and time and fate and entropy.

What is the spark of love when such cold winds from so dark and wide an abyss blow?

In this tale, we have a rare glimpse of Conan and his lover Belît, fair and fierce as a lioness, speaking of these deeper matters. We overhear just enough to imagine what sort of gods must rule, or be thought to rule, a world where hope is folly, and strength is the sole virtue.

The dialog bears repeating at length. This scene takes place just after Belît decides to risk her ship and life and sanity in a venture they both know to be deadly. Neither know how many, if any, of the souls aboard are fated to survive. Belît asks a direct question:

“Conan, do you fear the gods?”

“I would not tread on their shadow,” answered the barbarian conservatively. “Some gods are strong to harm, others, to aid; at least so say their priests. Mitra of the Hyborians must be a strong god, because his people have builded their cities over the world. But even the Hyborians fear Set. And Bel, god of thieves, is a good god. When I was a thief in Zamora I learned of him.”

“What of your own gods? I have never heard you call on them.”

“Their chief is Crom. He dwells on a great mountain. What use to call on him? Little he cares if men live or die. Better to be silent than to call his attention to you; he will send you dooms, not fortune! He is grim and loveless, but at birth he breathes power to strive and slay into a man’s soul. What else shall men ask of the gods?”

“But what of the worlds beyond the river of death?” she persisted.

“There is no hope here or hereafter in the cult of my people,” answered Conan. “In this world men struggle and suffer vainly, finding pleasure only in the bright madness of battle; dying, their souls enter a gray misty realm of clouds and icy winds, to wander cheerlessly throughout eternity.”

Belît shuddered. “Life, bad as it is, is better than such a destiny. What do you believe, Conan?”

He shrugged his shoulders. “I have known many gods. He who denies them is as blind as he who trusts them too deeply. I seek not beyond death. It may be the blackness averred by the Nemedian skeptics, or Crom’s realm of ice and cloud, or the snowy plains and vaulted halls of the Nordheimer’s Valhalla. I know not, nor do I care.

“Let me live deep while I live; let me know the rich juices of red meat and stinging wine on my palate, the hot embrace of white arms, the mad exultation of battle when the blue blades flame and crimson, and I am content.

“Let teachers and priests and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.”

They continue to talk, and Belît contradicts, or, at least, challenges Conan’s stoic indifference to the question of the after-world. In ringing tones, she avers that there is life after death, and, yes, something stronger than that:

“There is life beyond death, I know, and I know this, too, Conan of Cimmeria–” she rose lithely to her knees and caught him in a pantherish embrace–“my love is stronger than any death! …

She adds:

“Were I still in death and you fighting for life, I would come back from the abyss to aid you–aye, whether my spirit floated with the purple sails on the crystal sea of paradise, or writhed in the molten flames of hell!

“I am yours, and all the gods and all their eternities shall not sever us!”

That note of defiance against all pantheons should shock and delight any schoolboy reader, and perhaps, if the fickle goddess of love feels generous, he will meet a mate able to voice as passionate a fidelity for him, as the pirate queen for her barbarian.

Nor is her boast in vain.

Let it be noted for the record that this conversation is broken off when a giant river snake attacks one of the crewmen, yanking him screaming from the deck, and Conan must leap up and slay the monster in vengeance. The question of death and afterlife is not an academic one.

Several things are interesting here.

First, this is more authentic than it might first seem. The remark that Mitra must be strong because his people prosper could have been taken straight from the lips of any pagan in the classical times. The reason why Rome routinely captured the idols of conquered cities and brought them home was to show the strength of her gods over those of strangers.

Second, Conan’s noncommittal attitude is one reflected in the writings of later classical writers: the pagan philosophers often would allow that the gods exist, since the world could not arise of its own power out of nothing, but the stories poets tell are regarded as fable, so their cautious attitude is to allow the worship of all, and avoid provoking any.

Third, the awful belief that the after-world is but a realm of shadows where the dead exist in joyless gloom forever comes straight from Greek depictions. Even the somber Norsemen, who believed that the bravest of the battle-slain enjoyed nightly feasting and daily warfare in Valhalla, painted a more cheery picture than Homer paints of Hades. The greatest hero of the ILIAD is seen in the ODYSSEY lamenting death and wishing for life, if only as a slave to a poor dirt farmer.

Fourth, while surely no tribal gods in real life were as dismal and useless as Crom, there is many a god who demands horrid sacrifices, but whose main providence seems to be merely that they issue no curses, blight no crops, and allow the spring to return after winter.

The Irish dragon-god Crom Cruach, for whom the invented Cimmerian god is named, from what little we know of him, was as bloody a harvest god as Moloch or Saturn, who are remembered to this day for their taste for slain children.

In any case, we are not hearing an account from a shaman or bard of the Cimmerians, but that opinion of a cynical warrior who has walked many lands, and seen many temples and idols, all of whom no doubt have more votaries and fairer houses than whatever circle of standing stones was reared to honor Crom on the gray hills of the chilly north. If Crom were adored by goatherds or farmers at mayday or harvest time, Conan would not share in their festivities.

Now, that said, nonetheless Crom is the most dismal gods of all the invented pantheons of storybookland, aside from Lovecraftian Old Ones. He answers no prayers and only sends curses. But Crom has one grace in common with the star-god worshiped by the hard and austere Roman Stoics of old: he equips man at birth with enough virtue to endure, and to continue the fight.

Conan sees no point in asking for more.

Conan then utters perhaps the most stirring oration in favor of agnostic indifference ever penned. He propounds a neat paradox to prove it is an illusion to call life an illusion. The disputes of priests and philosophers mean nothing, compared to the simple and raw animal pleasures of life: meat and wine for this gluttony, fornication for his lust, and the rage of murderous warfare for his wrath. He burns with life, he loves, he is content.

I doubt the doctrine of hedonism has ever been voiced more elegantly or trenchantly. If anything, Conan’s doctrine is more profound than mere hedonism, because it is a harsh life, one known to end in death, that is being proposed.

Hence, despite living in pursuit of what are, in truth, three of the seven deadly sins this worldview at its foundation is stoical, and proposes virtues of long-suffering, fortitude, and manly contempt for pain.

Like many a primitive tribesman coming across the strong drink brewed by his more civilized cousins, he has a weakness for grog. But none of the pleasures Conan seeks are refined: he is not an opium smoker. None are corrupt: he is not a sodomite. His are not the vices of a civilized man. He is not an aesthete, nor a gourmand. His tastes are direct and plain, not jaded or decadent.

Of course, this philosophy of agnostic hedonism strikes me as being itself decadent. The praise of the simple life is something no one living the simple life is likely to voice. This philosophy is certainly not the kind of thing one sees reflected in Norse epics, Greek myths, the tales told by tribesmen in America or Africa or in the Mahabharata of India.

A real barbarian would never say voice this creed: only the Noble Savage of modern (or, at least, of Nietzschean) popular imagination.

Real primitive philosophy emphasizes real fundamentals, that is, the things needed for daily survival in the setting of a tribe, village, or city-state: duty to clan and chieftain, the need to avoid overweening pride, the shamefulness of cowardice in men or adultery in women, the need to honor the elderly and avoid false speaking, and the countless taboos needed to avoid the disfavor of the gods.

Now, rousing as this speech is, I pause to wonder at the author’s real intent. I will venture no opinion, because I know all too well from my own experience the unwisdom of attributing the author’s opinions to his invented characters. Since the muse lurks in a poet’s mind in that twilight zone between reason and dream and madness, often an author may not know himself what he means.

On the other hand, there is enough matter in the text to at least arouse the suspicion that, whatever the author’s intent, the tale is not meant to affirm Conan’s bold speech as entirely true.

He makes a boast in defiance of the gods as bold as hers, or, at least, in contempt for the questions touching the afterlife.

But, unlike hers, his boast fails.

She keeps her word. He does not.

I speak, of course, of the final scene. As promised, when Conan is fallen in combat, and on death’s brink, the shade of Belît returns from the dead, red-lipped and ivory-skinned, her body gleaming in the moonlight, her hair a black and wild cloud around her; and she stabs Conan’s attacker and saves Conan’s life. There is time for a single, elemental, flaming glance of love, but no words.

So she did exactly as she said, and, indeed, won the argument unambiguously: returning as a ghost is one sure way of proving that there is life after death.

And he? Twice he boasts. One he says the raw pleasures he can rip from life will content him. Once he says even if life is an illusion, he is content with it.

He slays the killer of his love in red battle just as he says he craves. He had days of love and wine, piracy and slaughter, and lived life to the utmost.

And then what?

Belît had been of the sea; she had lent it splendor and allure. Without her it rolled a barren, dreary and desolate waste from pole to pole. She belonged to the sea; to its everlasting mystery he returned her. He could do no more. For himself, its glittering blue splendor was more repellent than the leafy fronds which rustled and whispered behind him of vast mysterious wilds beyond them, and into which he must plunge.

Despite his bold talk of godless pleasures and blood-soaked ventures, in the last, he is not content. The sweetness is gone. The splendor and allure is lost.

There is something more to life than he said, and something stronger than death. There is love, whose mighty kingdom extends beyond the world.

Life is an illusion after all, or so the story implies: because the death that seems so real and final at the last gives way to something more.

Conan says one thing, but the story itself tells a different tale: Life is an illusion, O Conan! But you are real: for you have loved and have been loved in return.

Let no man boast himself content without it! Men need love, and nothing less than love beyond life, eternal life, is worthy of the name.

Here is the somber curtain line of this tale:

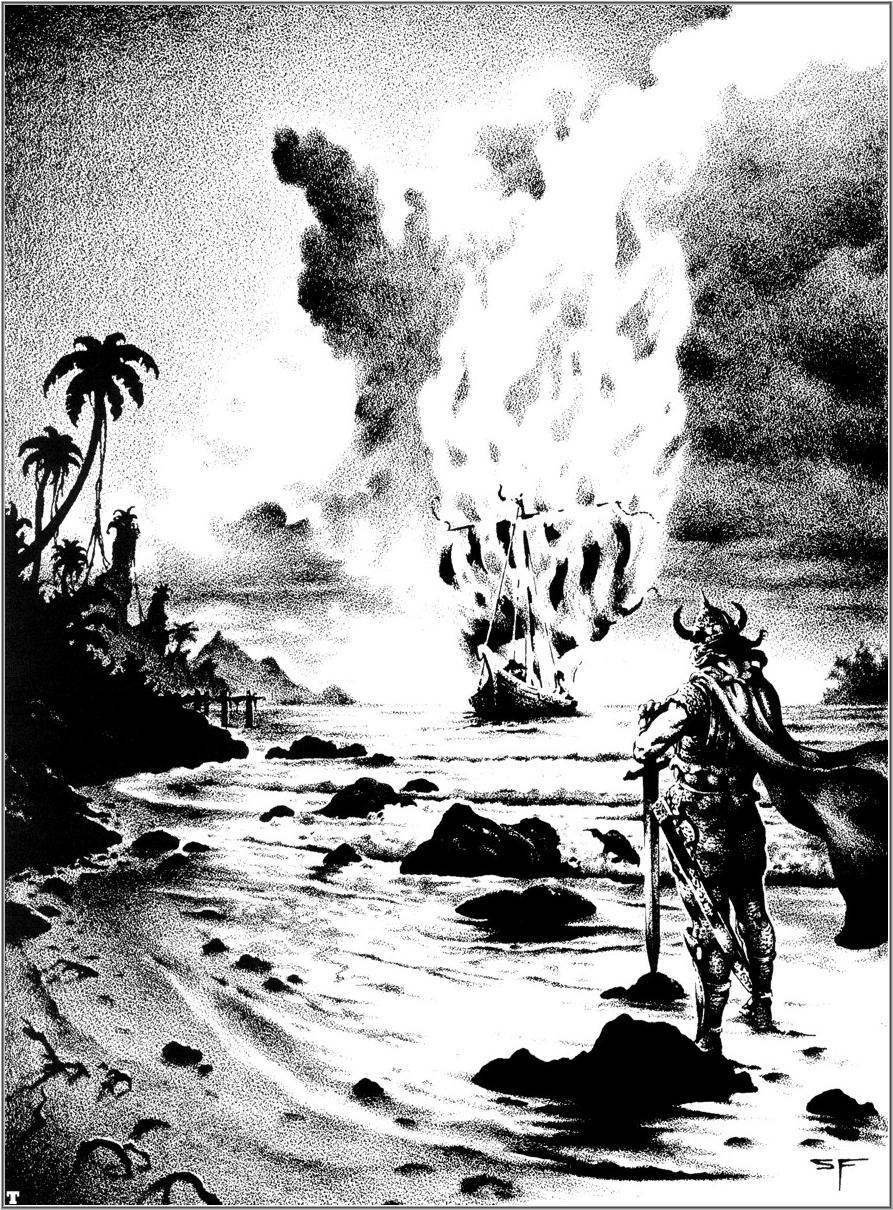

So passed the Queen of the Black Coast, and leaning on his red-stained sword, Conan stood silently until the red glow had faded far out in the blue hazes and dawn splashed its rose and gold over the ocean.