Time Travel is Always Annoying

In science fiction stories, there are a limited number of ways to explain the conundrum of how time travel might work if it could work (obviously it cannot) but still to make a presentable and dramatic story.

I doubt I can list all the various answers of the various imaginative authors who have attempted in an entertaining way to address the paradox. It makes for entertaining bull sessions by college students and philosophers, however.

But I can mention some basics:

In effect, the effort is to see how you can keep one or both of the appearances of cause and effect and of free will. Drama needs both cause and effect (because your hero’s action have to have consequences) and free will (because your heroes have to take actions, not just passively react).

But if Time Travel works, cause and effect, at least as far as the time traveler is concerned, are reversed. If he is from his own future, he knows his own future, and so he knows what he is going to do, or, at least, what he did do the first time he passed through the scene. If he acts on that information and interacts with himself, he changes his own past, which, logically, includes the chain of cause and effect leading to the events he remembers in his memory.

So there are two perils for the story-teller: because the time traveler knows everything that is going to happen before it happens, either there is no tension because the time traveler cannot lose, or there is no humanity because the time traveler cannot win. In the first case, the time traveler is like unto a god, because he knows everything in advance; and in the second case, the time travler is like unto a robot, because he can change nothing.

How does a cunning writer thread a path between the horns of such a dilemma?

The oldest and most traditional answer is one seen in Robert Heinlein’s “By His Bootstraps.” His answer is that free will is an illusion, something that seems to exist when you are acting, but which is seen not to exist when a version of you from a later period in time goes back into your scene.

Both the events as portrayed in his memory and in yours will somehow just so happen to play out exactly as you remember them, no matter from which point of view you observe the scene. You will even find yourself saying the exact same words the other version of you heard (or will in his future hear).

Heinlein’s answer is that time travel paradox is simple: they cannot exist because you cannot create them because you never did. You cannot change the past because you never did.

I call this the oldest answer because it dates back to the story of Oedipus: Any interference in the past is like Oedipus futile efforts to escape fate: once he hears the prophecy that he will kill one and wed the other, by running away to a distant nation far from the simple shepherds he wrongly thinks are his parents, he accidentally encounters his real parents, killing one and wedding the other. Your effort to escape fate is exactly what brings it about.

Even if you walk into a scene with an earlier version and intending to introduce a change into the scene, for some reason, when you actually get there, you will find you have a good reason not to.

This is, I think, the least satisfactory of all time travel solutions, because it basically means the story stars a robot programmed to think he has free will, but he does not.

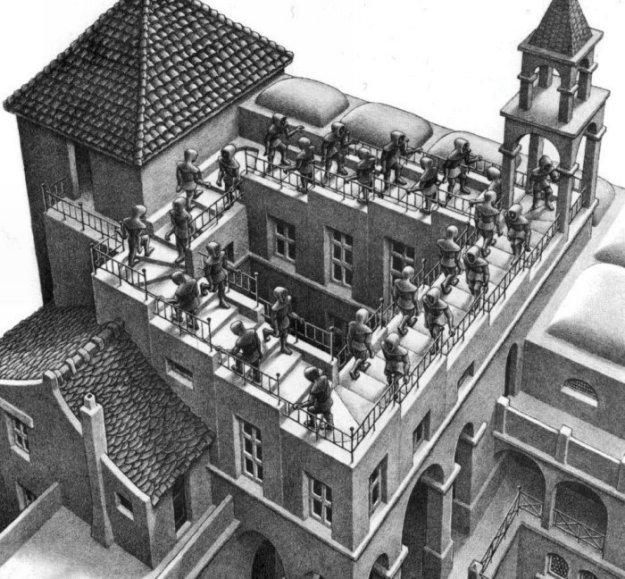

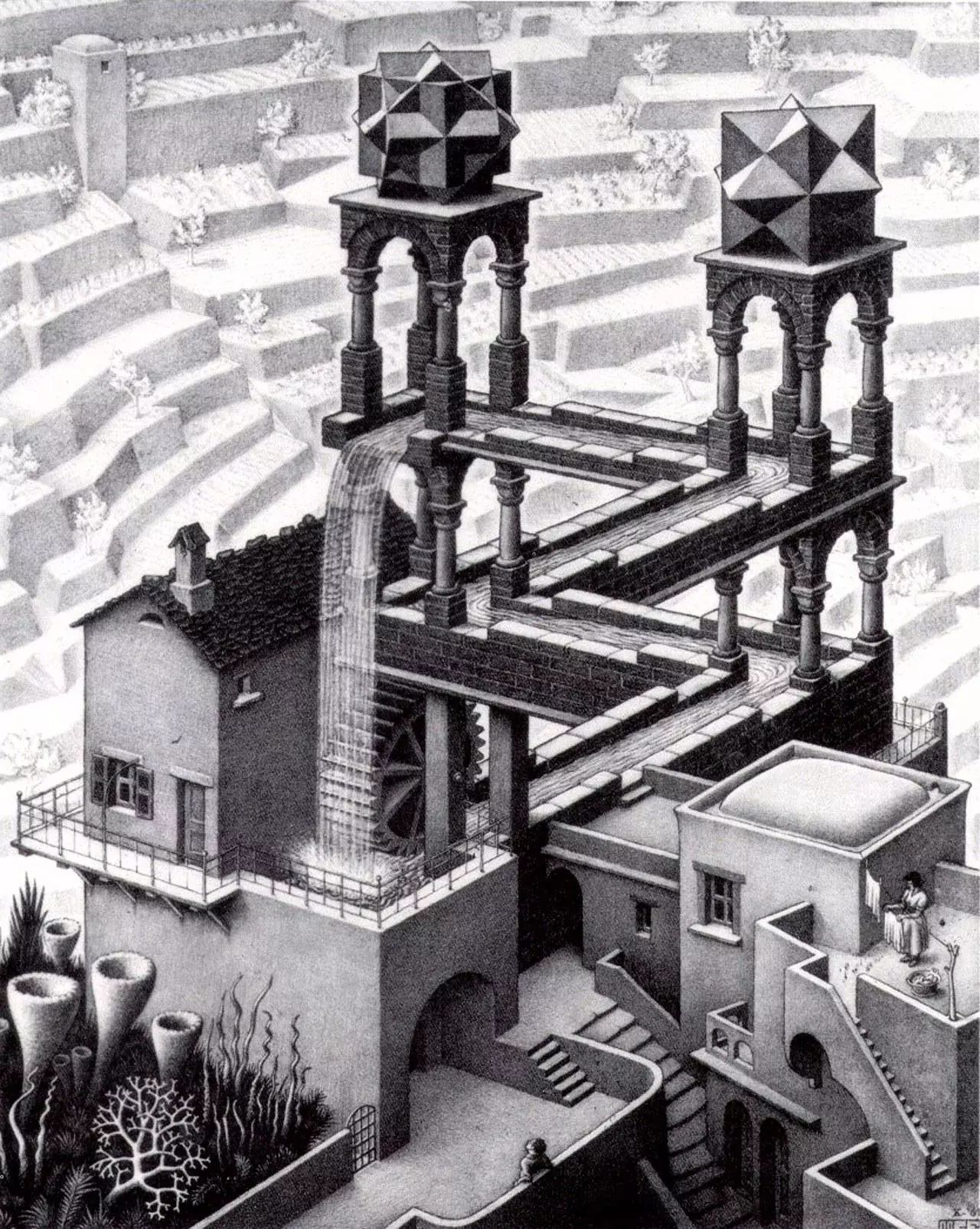

Like an Eischer drawing of a waterfall that falls into itself, or of a stairway that climbs ever upward back to its starting point, it is an story where each scene makes sense in its own way, but the whole picture does not: which is the whole appeal both of Eischer drawings and of fatalistic time paradox stories.

In terms of writing the scene, the character also has to be drunk, or forgetful, or mistaken about what he is seeing, or kept in ignorance about crucial facts (which, for some reason, he does not tell to himself during the time travel escapade) or the character at the moment of decision needs to be provided with an artificial reason why he does not want to change the past once he arrives, despite the fact that he is a time traveler who traveled into the past in order to change it.

Robert Heinlein nicely adopts all these reasons, and has his main character decide to be the time traveler from whom the younger time traveler is trying to steal the secret of time travel, without noticing or knowing that the two or three versions of himself that he meets all share the same face.

For better or worse, there is not much point in telling this particular type of time paradox story again, because of the strict limitation of making a main character make no decisions at any point in the story. He is merely a passive observer (albeit one who thinks he is making voluntary actions) in the story of how the time loop loops back on itself.

The appeal of the story is the cleverness of presentation. There is no way to get such a story to have drama in its own right.

Indeed, the main character, who is also the sole character, in the Heinlein story has no personality nor distinguishing characteristics whatsoever, except, perhaps, the distinguishing characteristic that he is the least observant person on Earth, next to Lois Lane. (At least in two scenes he has this main character talking to himself without recognizing his own face.)

He is a non entity. I had to look up the story to remind myself of his name: Bob Wilson. Bob the Time Traveler.

The second solution is the opposite: the appearance of fatalism s the illusion. There is not really such a thing as cause and effect, so that when you go back and change the past, all that happens is that you break the illusion, and you become a something like a ghost, an insubstantial being unable to change anything.

In this solution, you can change the past, but if you do, the only thing you can do is eliminate yourself.

This was the conceit of an Alfred Bester story called ‘The Men Who Murdered Mohammed’, and, again, for obvious reasons, there can be no drama in this story, only the cleverness of the presentation, as the main character pierces the illusion and figures out the truth of the matter, and is horrified to discover that he has, in effect, destroyed himself.

The main character, again, is a cipher. Let us not bother to look up his name. In this case, Bester plays the idea for laughs, so there is a gallows humor to the idea that if you go back in time and change things, the only one you eliminate is yourself.

So both of these solutions, the two extremes, are unsatisfactory except as a one-shot story with no sequels, where instead of drama we have the slow revelation of the mystery of how time travel works, and, once that is known, there is no point to traveling in time.

In the first case, the fatalistic universe, there is no point because everything you are about to do is already set in stone, and the only thing time travel can do is make you aware of your own helplessness; and in the second, you are free to do anything, but nothing has any effect on anything.

It is not the particular story, but the idea of time travel itself causing the difficulty for the writer. Drama requires that actions have consequences, and requires that acts be consequential.

In a time travel story, any and all problems now can be solved before they arise thanks to the timely advice and intervention of future versions of the hero clearing obstacles from our hero’s path. Time travel makes him omniscient, hence omnipotent, hence no human drama. The Time Traveler becomes a god.

It is good for a laugh, as in BILL AND TED’S EXCELLENT ADVENTURE, where the heroes merely agree to use the time machine they hope to recover to go back later and leave convenient tools and keys and suchlike for themselves in a nearby potted plant, whereupon the keys (or whatever) are discovered to have already had been hidden in the potted plant. But it does not make for drama.

The second is that nothing the time traveler does has any meaning, because he already knows the outcome, and for one reason or another, he either cannot or does not have the power or ability to change what he already knows is going to happen.

This is good for a moment of desolate melancholy, as we see in Dr. Manhattan in Alan Moore’s WATCHMAN, where an omnipotent superhero, by being able to see all the future at one glance (which is a type of time travel, if only of information) finds himself trapped as if in a soulless clockwork, unable to change even the smallest thing. But it also does not make for drama.

A third option is a compromise position that I have seen several authors attempt, but none more succinctly than Fritz Leiber in “Try to Change the Past.” The conceit here is that the past can be changed, but only if the universe, which is naturally resistant to change, cannot arrange a coincidence to bring about the closest possible analogy of the original events. Call it event inertia, or even Murphy’s Law.

In this story, the time traveler is desperately trying to prevent the event of a man being shot through the skull. His motive is sincere: he is the man. He runs through the scene several times, emptying the gun, hiding the gun, and so on, but some odd coincidence provides bullets or a spare weapon to the murderess just in the nick of time. Finally, he outsmarts the universe, and makes it impossible for the murderess to enter the room and find the revolver, but he sees himself step on to the balcony just in time to be hit in the head by a pebble-sized micrometeorite that happened to be winging its way through the atmosphere just at that particular second.

Again, the irony of a story like this is a one trick pony: the drama is the cleverness with which the malign universe outsmarts the doomed time traveler. Once he discovers the rule of time travel (you have free will, you just cannot do anything with it) the story is over.

A fourth option is merely not to raise the issue at all.

You can tell a story with a time machine in it where the machine merely serves to get the action going and set the stage, but then, because it is broken or quirky or out of power or a dinosaur stepped on it the moment you dismebarked, you cannot use it to go back five to ten minutes and get the machine out of the way of the oncoming dinosaur.

This is what most mainstream time travel stories are like. They do not deal with time paradoxes because such things are not what the story is about.

For example, in the TV show TIME TUNNEL, nothing that Doug and Tony, the lost scientists, ever did in the past, as they landed aboard the Titanic or dropped down before the gates of Troy, had the effect of changing the events leading up to the creation of the Time Tunnel. We never see the scientists who sit and watch Doug and Tony’s adventures suddenly change into parallel people.

As best I recall, Doug and Tony simply would fail to alter any historical events: they could not convince the captain of the Titanic to change course, nor convince the Trojans to leave the wooden horse outside the gates.

It was a time travel show without enough time travel to allow the characters to travel in time at will. Any places they landed was an accident. Nothing they did made a different to the show next week.

Now, even as a kid (for I was a smart alecky kid) I noticed that, like the TARDIS of Doctor Who being always malfunctioning, or like the drunkenness and bad memory of Bob the Time Traveler, the time machine in this case never functioned properly enough to actually act like a time machine, that is, you could not use it to do a do-over and solve your problems that way.

We never see 65 year old Doug from the year 2000 pop into existence in the buried Project Time Tunnel facility in 1966 where the three scientists are trying to fix the broken machine, announce that the 44 years of additional research solved the focus and time-wobble problems, plug a gizmo into the control panel, and yank his younger self immediately back into the home time.

We never see 85 year old Doug from the year 2020 bampf back to a spot in time a few weeks earlier when Tony was first sneaking without authorization into the machine, shoot him with a stun ray, and haul him to the guardhouse for a court martial.

As best I recall from the first few decades of DR WHO, the Tardis was broken, and could be used to get the Doctor and his companions into the time period or onto the planet where the action would be happening, but it could never actually be used, for one reason or another, to change the events of the past hour and solve the problem.

So, to be frank, option four is not really an option: it just has the time machine able to get your heroes on stage but not to be used as a time machine to undo unwelcome past events.

A fifth option is to have multiple universes: a new timeline breaks away from the original branch at any moment when there is interference in the time stream.

So, when you go back and kill your grandfather when he was a child, the universe forks. In the original fork, he was never attacked, he founded your family; in the new fork, he is slain, and the universe goes along without him.

Nearly all the science fiction stories I have read or seen, from BACK TO THE FUTURE to the made-for-TV movie (based on my idea) TIMESHIFTERS aka THRILLSEEKERS have this multiple-world theory in one form or another.

It seems to allow for everything we want out of a time travel story, that is, the excitement of shooting dinosaurs with modern elephant guns, and seeing Yankee inventors mock King Arthur’s court, with none of the headaches of paradox.

In stories of this type, the writer has a choice: does the creation of the new time line have a bad effect either on itself or on the original? Or do they exist in peaceful parallel?

In the first case, the time travelers creating new lines creates a time pollution or entropy effect that weakens the fabric of the universe. In the second case, time travel is free.

If time travel is free, go to town!

No matter how tangled it might get, nothing stops you. If you go back and kill your grandfather, but future you arrives a minute before you pull the trigger and shoots you and saves gramps, but then future him arrive a minute earlier yet, shooting him and saving you and letting you kill gramps, but then gramps rips aside his mask and reveals itself to be a killer robot made by your grandson who is sick and tired of your time travel shenanigans, so he arrived years ago, replaced grandfather with the robot, and his grandson married your grandmother… all those things are allowed to happen, and each time line pops into existence each time you change your mind has no deleterious effect on any of the others.

Myself, I am only worried that the Colepterous race that arises fifty million years from now will exist in one and only one of the time lines the unwary time traveler will create, and, displeased, will send their agent back to his year of origin, and eliminate him and all his works in order to prevent the creation of yet another even more unlikely timeline where the Great Race of Yith arises in the immeasurably far future, who will then send their minds the unthinkably distant past, and from that base cast their minds forward again, perhaps to replace and overwhelm the Colepterous peoples.

So nothing stops the time traveler in the cost-free multiverse time travel set up, except for himself (or if he sets in motion any chains of events leading to a time traveler like himself) trying to stop himself.

The most well developed exploration of this kind of cost-free time travel was in David Gerrold’s THE MAN WHO FOLDED HIMSELF, which I can only recommend with hesitation, because of the scenes where the main character decides to become his own homosexual lover with himself. Not every writer is inventive enough to coin a new perversion!

Aside from this one wart, the book itself is clever in its speculative rigor.

But if time travel is free, and the time traveler has the liberty to keep tinkering with his own past until he find the time line that sates all his desires, there is very little drama to be found aside from the psychological drama of the time traveler discovering, as a man with a lamp holding a genii will discover, what his true inner nature and inner psychology are like, once he is allowed to remake the universe in his own image.

So call consequence-free time travel our fifth option. But if the creation of new timelines weaken or use up the original line, or even overwrite it, then this is a sixth option.

This sixth option is that time travel is possible, but has a price: under these rules, time travel by its nature will eventually eliminate itself.

If the original timeline, the one where time travel is invented, is overwritten, either it will be overwritten by a new timeline where another set of events leads to the discovery of time travel, or it will be overwritten by a timeline where no one ever invents time travel.

In the first case, the new timeline will be overwritten again and again as time travelers monkey with the past, and in the second case, the monkeying will cease as the last time traveler eventually erases himself by meddling with his own past.

I am not the first science fiction writer to notice this feature of time travel: if changing the past is possible, and time travel is not inevitable, time travel by its very nature always eliminates its own inventors.

We can call this NIVEN’S FIRST LAW OF TIME TRAVEL, because Larry Niven is the first one (at least to my knowledge) who coined the law in his essay ‘The Theory and Practice of Time ‘ appearing in his anthology, ALL THE MYRIAD WAYS.

Again, in my estimation, the drama of time travel in tales of this type is mostly psychological: the struggle of the time traveler to resit the lure of what is basically and addictive drug that will one day destroy him. My own short stories gathered in the anthology CITY BEYOND TIME is an exploration of this idea.

But in the multiple world time travel story, even if the time travel is free (as in our fifth option) or self destructive (as in our sixth) there is still another complication. The one thing that the writer has to decide about a multiple world timeline is this: can time travelers from a point in your future, come back from a point later than your starting point and interfere with your efforts to create the new timeline?

Because that is the plot to BACK TO THE FUTURE II.

For the multiple world theory does not actually eliminate the time paradox after all, it just introduces the element of later time travelers trying to undo the mischief earlier time travelers. In this movie, Biff undoes the effort of earlier Marty and in turn later Marty attempts to undo what was done by earlier Biff, while he is undoing earlier Marty.

BACK TO THE FUTURE handles the time paradoxes involved merely by giving the time traveler a ticking clock: his gear and then his person will slowly fade from view and become non real if the events leading up to his own existence are not put back into their proper place before the end of the two hour movie. The time traveler is not perfectly immune from erasing himself, but he has a grace period.

There was a similar sleight of hand in TIMESHIFTERS, which I rather doubt any of my readers has ever seen. (It is the closest thing my fans will ever see to a movie written by John C Wright. But I did not write it, my friend Kurt Inderbitzen did: but I gave him the basic pitch idea.)

The pitch idea is this: since time travelers run the risk of changing the past, what can it be used for? Obviously the only thing time travel can be safely used for it sight seeing, where the observer changes nothing. What sights would travelers be likely to see? Obviously, famous disasters, such as the Hindenburg going up in flames. The hero in TIMESHIFTERS is a reporter who finds the same man’s face in several crowd shots taken at the site of famous disasters. Even though the shots were taken years and decades apart, the man is the unchanged. While the reporter is sitting on an airplane puzzling over the photos of this mysterious man, a little girl in the next seat leaned over and asks who that man is. The reporter says he does not know. The girl points across the aisle. The man, the sightseer of all the great disasters in history, is sitting two seats away, an eager look on his face …

But how was the question of time paradox handled? Because the reporter is damn well going to try to change the disastrous event about to happen that the time traveler regards as the dead past, or else die trying.

The long and the short of it was that the time traveler himself had ‘hardened memory’ so that if anyone or anything, including other versions of himself, changed the past, he would recall the unedited version. His bosses who phoned him from the future with instructions were housed in a bunker that was immune from the time changes, and, like Marty McFly, this gave them a grace period during which they had to send back agents to stop the prior time travelers from meddling with the proper course of events, before they would disappear.

Obviously, this idea of hardened memory, or partial immunity to time travelers changing your past, or a grace period of delay makes no sense if you think about it. (How can it be an event to have events catch up with events moving at the speed of events? If Marty McFly’s photo of his family is fading because it was never taken, how can he be holding it in his hands to watch it fade?)

So it is better to have a rock concert or lightning storm or a chase scene on the screen so that the viewer does not think about it.

The very best example of a story dealing with the ramifications of time travel where each new timeline created creates bad consequences was the short story ‘The Timesweepers’ by Keith Laumer, later expanded into a book DINOSAUR BEACH.

This is a story I can recommend to anyone who is a fan of the time travel yarn, because it holds what I regard as the final answer to all such stories, and it is told in Keith Laumer’s fast-paced hard-boiled film-noir style of no-nonsense action fiction.

The conceit here is one I would rather quote in full than paraphrase:

The Old Era temporal experimenters had littered the timeways with everything from early one-way timecans to observation stations, dead bodies, abandoned instruments, weapons and equipment of all sorts, including an automatic mining setup established under the Antarctic icecap which caused headaches at the time of the Big Melt.

Then the three hundred years of the Last Peace put an end to that; and when temporal transfer was rediscovered in early New Era times, the lesson had been heeded. Rigid rules were enforced from the beginning of the Second Program, forbidding all the mistakes that had been made by the First Program pioneers.

Which meant that the Second Program had to invent its own disasters—which it had, in full measure.

… [in the] Third Era … the second great Timesweep attempt [was] designed to correct not only the carnage irresponsibly strewn across the centuries by the Old Era temporal explorers, but to eliminate the even more disastrous effects of the Second Program Enforcers.

… Or so they thought. After the Great Collapse and the long night that followed, Nexx Central had arisen to control the Fourth Era.

The Nexx Timecasters saw clearly that the tamperings of prior eras were all part of a grand pattern of confusion; that any effort to manipulate reality via temporal policing was doomed only to further weaken the temporal fabric.

When you patch time, you poke holes in it; and patching the patches makes more holes, requiring still larger patches. It’s a geometric progression that soon gets out of hand; each successive salvage job sends out waves of entropic dislocation that mingle with, reinforce, and complicate the earlier waves—and no amount of paddling the surface of a roiled pond is going to restore it to a mirror surface.

The only solution, Nexx Central realized, was to remove the first causes of the original dislocations. In the beginning, of course, the disturbances set up by Old Era travelers were mere random violations of the fabric of time, created as casually and as carelessly as footprints in the jungle. Later, when it had dawned on them that every movement of a grain of sand had repercussions that went spreading down the ages, they had become careful. Rules had been made, and even enforced from time to time. When the first absolute prohibition of time meddling came along, it was already far too late. Subsequent eras faced the fact that picnics in the Paleozoic might be fun, but exacted a heavy price in the form of temporal discontinuities, aborted entropy lines, and probability anomalies. Of course, Nexx, arising as it did from this adulterated past, owed its existence to it; careful tailoring was required to undo just enough damage to restore vitality to selected lines while not eliminating the eliminator.

Without spoiling the surprise ending, I can tell you that a disaster overwhelms the Nexxal time travel base, and the entire hidden organization, because there is a Fifth Era meddling with them without their knowledge, and a Sixth in turn meddling with them … and ….

All are trying to undo the mistakes of the past, but, of course, if they undo the mistakes that give rise to the events that give rise to them, they eliminate themselves. Only in the final era can the final choice be made.

This time travel story contains the drama and the strong characterization most others lack. I do not need to look up the name of the main character, since I remember it from forty years ago: it is Igor Ravel. The tragic heroine is named Mellia Gayl.

But in the final analysis, like all other time travel stories, DINOSAUR BEACH is about the revelation, slow or fast, of how time travel works, and what the price is, what the temptation is, and, more to the point, what the crucial decision about time travel itself says about the psychology and character of the time traveler.

I will not hide the fact that my own time travel stories are taken in mood and theme directly from the inspiration of the great Keith Laumer: because, honestly, I think his answer is the right one.

The only honest use of a time machine is to go back in the past and eliminate the invention of the time machine.