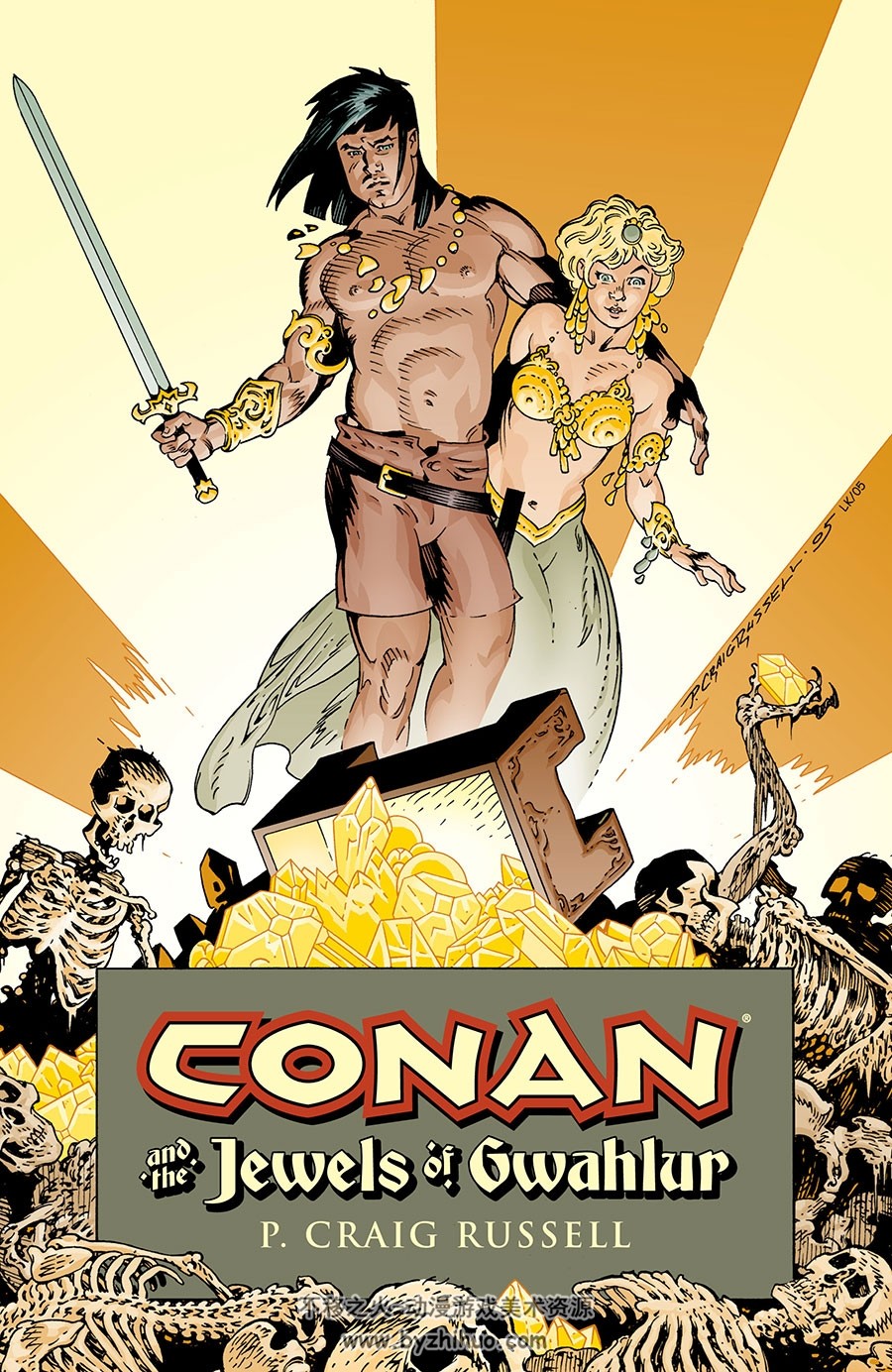

Conan: Jewels of Gwahlur

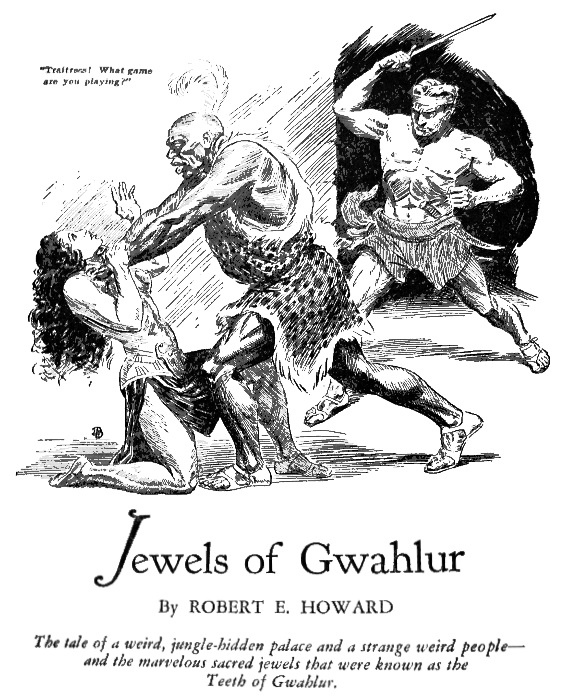

Jewels of Gwahlur was first published in Weird Tales magazine in March 1935, coming three months A Witch Shall Be Born. It is the fourteenth published story in the Conan canon.

This tale has been republished under the names The Teeth of Gwahlur and The Servants of Bit-Yakin.

Spoilers below.

Jewels of Gwahlur is neither the best nor the worst of the Conan Canon, but is somewhere in the middle. There is little to make it stand out from the other Conan stories, aside, perhaps, from the number of unexpected turns of the plot. There is a web of deception, with the deceivers being deceived in turn. Conan prevails due to his catlike stealth and lionlike courage more than his cunning wit — which he also uses

The side of the mighty Cimmerian on display in this yarn is the pilfering scoundrel rather than the barbarian mercenary or world-weary king.

Here, Conan has more in common with Cugel of Clever from the Dying Earth tales of Jack Vance than with the Noble Savage of Rousseau or the post-ethical superman of Nietzsche.

We have seen this side of him before in Pool of the Black One and Rogues in the House.

There is a second parallel with Rogues in the House, but it is one where Jewels is seen to be the inferior work, and less memorable. More on this later.

The word that best described Jewels of Gwahlur is not Sword and Sorcery (for there is neither a single swordfight nor chanted spell of eldritch sorcery in these pages) but instead would be the word picaresque.

This useful word, in case the gentle reader has not previously encountered it, refers to a genre where a rough and dishonest but appealing hero of low social class lives by his wits in a rough and dishonest but corrupt society.

The style is usually as cynical and roguish as the hero is. In a picaresque story, crime pays, but usually in coin of gilded lead, bright only outwardly, and beneath this, hard, cold, and heavy.

Tales of treasure hunters easily lend themselves to the picaresque approach, because in a such a story, there either is no true owner with a right to the trove, or, as in a heist story, the true owner is so despicable that no reader sorrows if he looses his loot. In a picaresque tale, the person being robbed is always a robber himself, or something worse.

In such an environment, questions of right and wrong do not come up. When questions of right and wrong never come up, everything is guided by sentiment. The so-called villains are those guided by unpleasant sentiments, as by being rude or sadistic, and the so-called heroes by pleasant, as by being kindly to women, children or furry animals.

We see this pattern repeated endlessly, as in the opening of Disney’s ALADDIN, for example, where the street rat steals bread — making him a thief and technically a bad guy — but the guards are mean, and the thief gives the bread to big-eyed waifs instead — a kindness prompted entirely by sentiment.

In Jewels of Gwahlur, Robert E. Howard has returned to the purple prose, vivid description, and manly lyricism of his best work. The leaden language seen in Howard’s previous tale, A Witch Shall be Born, is happily no longer evident.

Here is the opening. Note with what economy of words, the setting is established, described, the mood is set, the protagonist defined in a few, clear, sharp strokes:

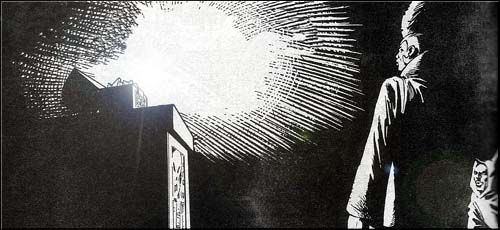

THE cliffs rose sheer from the jungle, towering ramparts of stone that glinted jade-blue and dull crimson in the rising sun, and curved away and away to east and west above the waving emerald ocean of fronds and leaves. It looked insurmountable, that giant palisade with its sheer curtains of solid rock in which bits of quartz winked dazzlingly in the sunlight. But the man who was working his tedious way upward was already halfway to the top.

He came from a race of hillmen, accustomed to scaling forbidding crags, and he was a man of unusual strength and agility. His only garment was a pair of short red silk breeks, and his sandals were slung to his back, out of his way, as were his sword and dagger.

Five short sentences, and the reader is already immersed in the story world beneath the dawn light above the jungle expanse, and wonders why the unusually strong and agile but barefoot hillman is scaling the insurmountable cliffs.

The setup is briefly explained: our antihero, Conan the Clever, has come to the legendary kingdom of Keshan in darkest Africa (or, rather, to the southern part of the Euro-African landmass that existed before the Mediterranean severed them) to winkle a trove of legendary jewels from the hands of the ebony-skinned kings.

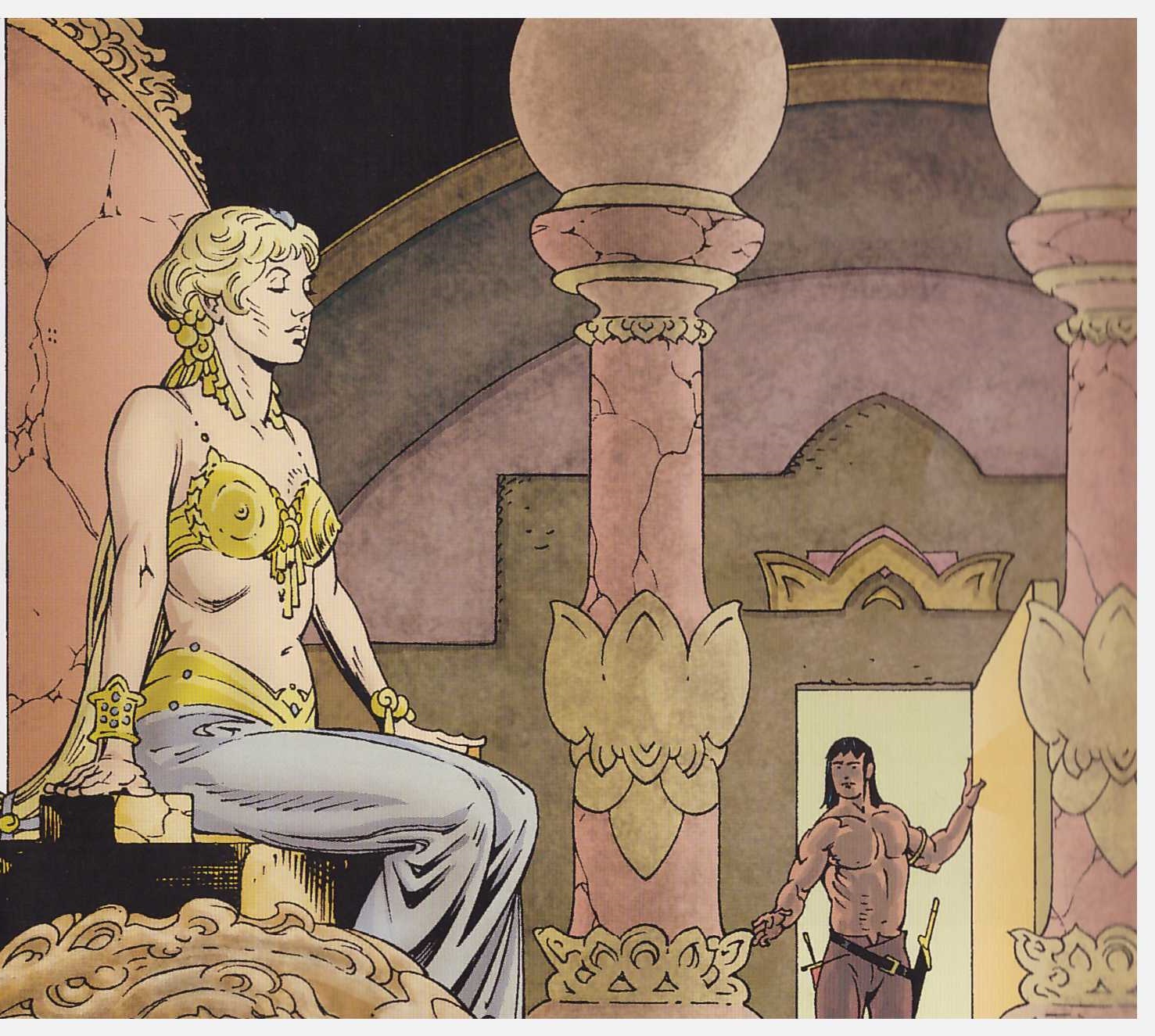

The jewels are kept in a sacred city in a hidden valley, from which all human life has long since excluded. In the empty temple-palace at the center rests the dead body of a sibyl, entombed and enthroned, perfectly preserved and incorrupt.

She is described thus:

Yelaya was coldly beautiful, even in death. Her body was like alabaster, slender yet voluptuous; a great crimson jewel gleamed against the darkly piled foam of her hair.

She is worshipped as a goddess, for the fair-skinned beauty has the ability to come to life again to offer oracular wisdom to her high priest, and tell the will of the gods.

But before Conan can discover the location of the secret city and its treasure, an old rival appears.

Thutmekri came to Keshan at the head of an embassy from Zembabwei. Thutmekri was a Stygian, an adventurer and a rogue whose wits had recommended him to the twin kings of the great hybrid trading kingdom which lay many days’ march to the east.

He and the Cimmerian knew each other of old, and without love.

Thutmekri’s plan is to falsify the pronouncements of the oracle, and have the sacred jewels turned over to him.

Then the false oracle will also decree the will of the gods is to have Conan flayed alive in the public square.

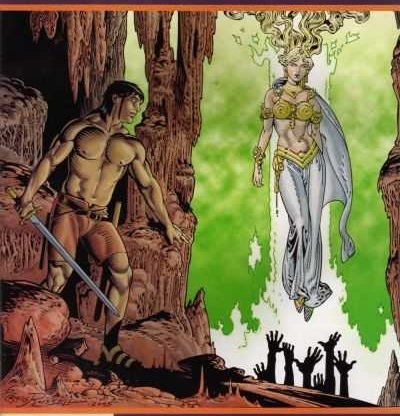

Of course, this calculation does not take into account the true will of the goddess, who may or may not be as dead as she seems…

Myself, I am delighted to hear of rivals to Conan, in his same line of work as a freelance cutthroat. To have a character, new to the reader, greeted by the hero as if he were an ancient foe, is a writer’s trick that automatically creates an illusion of background depth.

This type of thing is used to great effect, for example, in the film THE MALTESE FALCON — we never actually see the details of the background story, but a hint is all that is needed.

The names of the nations also serve as all the hint necessary to create the mood and atmosphere of the setting. The conceit of the Hyborian Age is that it takes place in the twilight of prehistory, so that certain names are dimly recalled as legend which then were current.

Keshan or Kesh is the ancient Egyptian name for Nubia, and Punt is Ethiopia. Zembabwei takes its name from the ruins of Great Zimbabwe (as did Southern Rhodesia in the real world 45 years after this story was published). Stygia, which is primordial Egypt, comes from the word Stygian, referring to the river of the underworld, Styx, the Hyborian name for the Nile.

Thutmekri’s allies include Zargheba, a Shemitish (read Bedouin) rogue, his slave Muriela, a Corinthian (read Grecian) dancing girl, and the corrupt priest Gwarunga, who tells him the secret entrance into the forbidden ruins. Leading the expedition toward the oracle is the high priest, Gorulga.

In a revelation so rare as to be unique, the high priest in this story is described as sincere and incorruptible. Conan here is talking to Muriela the dancing girl. She tells him Thutmekri’s plan to swindle the jewels of the kings of Keshan with a pious fraud.

Conan asks:

“Gorulga is a party to this swindle, of course?”

“No. He believes in his gods, and is incorruptible. He knows nothing about this. He will obey the oracle…”

“Well, I’m damned!” muttered Conan. “A priest who honestly believes in his oracle, and can not be bribed. Crom!…”

This is the sole example of a priest in the Hyborian Age who is not a hypocrite preying on the gullible. Robert E. Howard was no fan of organized religion.

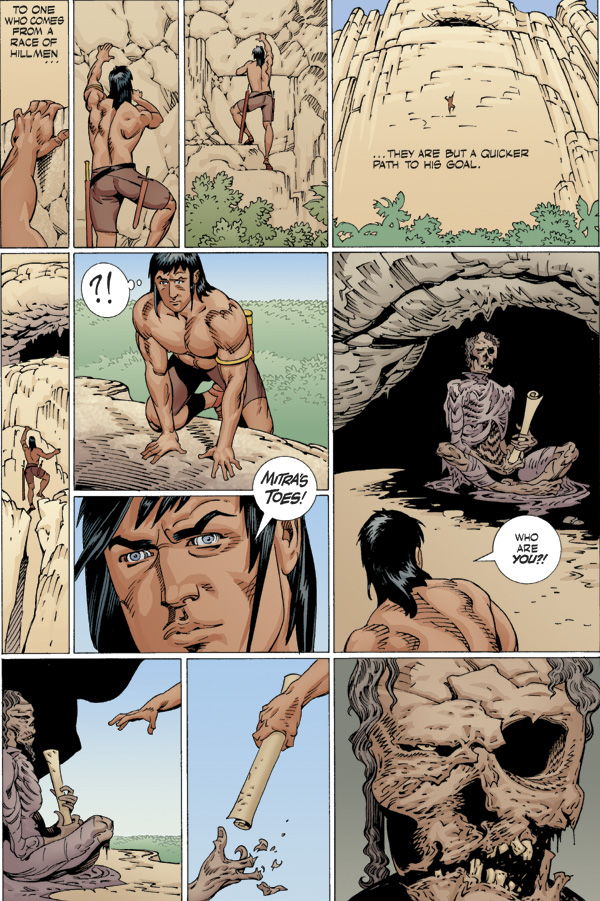

Another plot element here which is relatively rare in Conan stories is our barbarian hero using his familiarity with many tongues, gathered from his many travels, to puzzle out the meaning of an obscure scroll found in the claws of a mummified corpse.

Conan is not confounded with an overabundance of book learning, but this does not mean our noble savage is unintelligent.

Of course, just because the sacred ruins are empty of human life, this does not mean that they are not haunted by some ancient and deadly evil, nor does it mean that Conan the Rogue and his rival rogue Thutmekri are the only factions with an interest in the jewel.

I will not here detail the various plots and counterplots that clash in the buried darkness of the tombs and temples beneath the sacred city. I will say that of our cast of characters, half are dead by the end of the story.

I will also mention that, at one point, Conan is dumped into underground river, whose cold flood sweeps him away into dark depths. Whether this is merely the accident of an ancient floor tile giving way, or a deliberate trap set for him, is unclear. However, he must take his swordblade in his teeth to free both his hands to swim against the raging current.

We have seen countless pirates clutch blades between teeth to climb anchor ropes and suchlike, but this is the first time I myself can recall seeing this tiny detail of realism in an adventure romance:

He transferred his sword from his teeth to its scabbard, spitting blood – for the edge had cut his lips in that fierce fight with the river—and turned his attention to the broken roof.

I call this a picaresque rather than sword and sorcery partly in jest, but partly because there is so little swordplay here: it consists of two scenes where Conan deals one and only one blow.

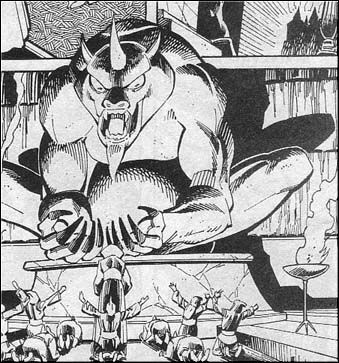

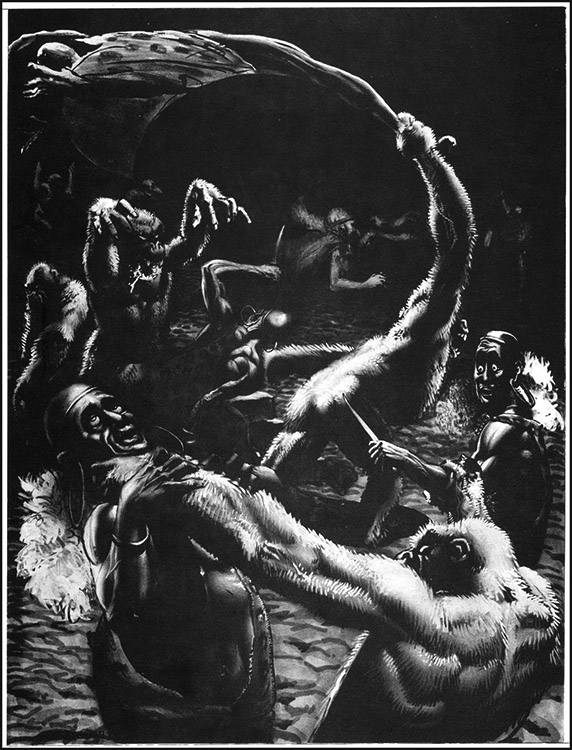

There is also a massacre of idolaters by an ancient evil emerging from behind their unholy altar to dismember and slay the whole company in a grisly cataclysm which Conan spies, but in which Conan takes no hand.

Whether there is any sorcery at all in this tale, or whether it is all just stage-magic and trickery, is a question best left to the reader. There are elements here which do not fit neatly with the mundane events of the world we know, but neither are they quite eerie enough to be something from a Lovecraftian universe of eldritch horror. This is more like a cryptid story — if a man sees a beast the world thinks extinct, the thing is a monster in one sense of the word, even if not supernatural.

The story is picaresque also in the tone, which is slightly different from the grim sobriety so often present in Howard’s Conan yarns. There is a trace of a tongue-in-cheek mood here, particularly when Conan comes across the dancing girl another rogue is setting up to imitate the undead goddess.

“Why, you sacrilegious little hussy!” rumbled Conan. “Do you not fear the gods? Crom! Is there no honesty anywhere?”

The fact that she has an outrageous accent that would give away the game to anyone who hears her — but that only Conan is well traveled enough to recognize it — is one more tongue-in-cheek irony.

It must be said that, of the list of hot-blooded half-clad beauties Conan had had clutching his knee in his various adventures, Muriela is the worst. She is the most helpless, the most frightened, and the most useless female of the lot, and clings to him every scene she is in, once a scene.

“Conan!” She made a spasmodic effort to go into the usual clinch, but the chains hindered her. He cut through the soft gold as close to her wrists as he could, grunting: “You’ll have to wear these bracelets until I can find a chisel or a file. Let go of me, damn it! You actresses are too damned emotional. What happened to you, anyway?”

He also swats her on her shapely bottom when first they meet. A partisan of the equality between the sexes, the barbarian is not.

But, again, this is in keeping with a picaresque, which is meant to show even likable characters in their worst light, rather than as a sword and sorcery, which emphasizes heroics in a world of brutality and unearthly evil.

The one thing a picaresque tale can have no trace of his real chivalry, real honesty, real goodness. In a picaresque world, all those things are illusions, merely bait for chumps. Life is poor, nasty, brutish and short.

Conan reflects on this as he goes back, sword in hand, to deal with a wounded man he left unconscious in a blood puddle:

The Cimmerian had lived too long in the wild places of the world to have any illusions about mercy. The only safe enemy was a headless enemy.

Let me here draw a contrast with ‘Rogues in the House’ which was very similar in theme, but not at all similar in tone.

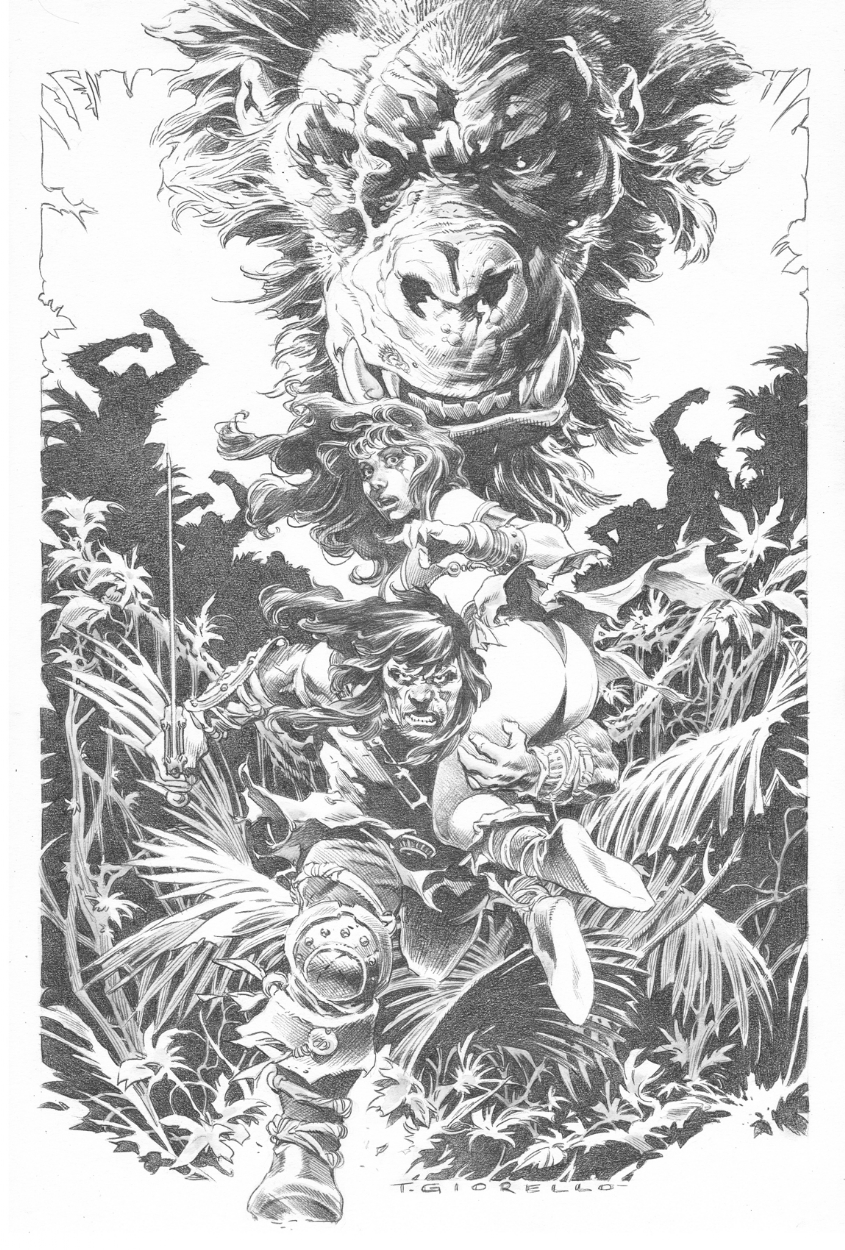

In both tales, Conan meets, and fights, an apelike ancestor of man, preserved in some forgotten corner of the unexplored world, half educated to be able to mimic men, or, at least take up the deadly weapons and dark idolatries of man, copying the motions without knowing their meaning.

When, Conan, after a deadly battle, overcomes the ape-man in ‘Rogues in the House’ his primitive but ironclad sense of barbarian chivalry demands the creature be buried with the honors due to a worthy enemy, perhaps the last of his tribe in all the world. The barbarian treats the ape-man as a man.

There is no trace of any such sense of honor here — the ape-man is merely a queer and deadly obstacle standing between Conan and the loot he craves. But then again, so are the men. The point of a fraud, after all, is to make a monkey out of the fool being fooled.

But in a picaresque, everyone is a bit of a fool, if only a sentimental fool. As mentioned above, in a world without moral rules, sentiment is the only guidepost, and there is neither clearly marked bounds of good and evil. Instead there is kind sentiment and cruel sentiment.

In the end, the box of treasure and the helpless beauty are tossed off a bridge, and Conan, beneath, has time to reach and catch only one. It is no spoiler to say he saves the girl.

Nor you nor I, dear reader, would have read these tales, for they never would have been published in the first place, had they starred a man who would let a helpless member of the fairer sex perish in the freezing waters of an unlit, underground sewer to snatch up some baubles of worldly pelf. Conan is not a postmodern hero, and this is not some postmodern dumpster-fire fantasy story about rape and incest.

Besides, what is wealth used for in a world of barbarian romance, aside from buying harem girls or alluring pirate queens? It is not like Conan needs the money to open that small blacksmith and hardware franchise in Ophir he had always dreamed to open, called ‘Crom’s Cast Iron – the answer to the Riddle of Steel is savings!‘

The story ends on a note that perfectly sums the theme of this, or any, picaresque:

“…You should have caught the gems and let me drown!”

“Yes, I suppose I should,” he agreed. “But forget it. Never worry about what’s past. And stop crying, will you? That’s better. Come on.”

“You mean you’re going to keep me? Take me with you?” she asked hopefully.

“What else do you suppose I’d do with you?” He ran an approving glance over her figure and grinned at the torn skirt which revealed a generous expanse of tempting ivory-tinted curves. “I can use an actress like you. There’s no use going back to Keshia. There’s nothing in Keshan now that I want. We’ll go to Punt. The people of Punt worship an ivory woman, and they wash gold out of the rivers in wicker baskets. I’ll tell them that Keshan is intriguing with Thutmekri to enslave them — which is true — and that the gods have sent me to protect them — for about a houseful of gold. If I can manage to smuggle you into their temple to exchange places with their ivory goddess, we’ll skin them out of their jaw teeth before we get through with them!”