Judgement Eve

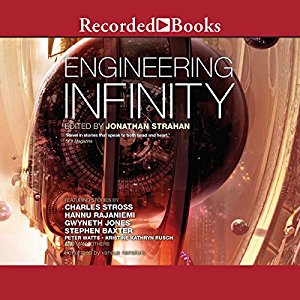

The esteemed Jonathan Strahan, whom, at one time, it had been my pleasure and honor to work on several projects, has recently published an audio version of an anthology from 2011, part of his 3-book ‘Infinity Project’ series

It is called ENGINEERING INFINITY.

I am pretty sure it is the only time I appear between the same covers as Stephen Baxter, Greg Bear, Peter Watts and Charles Stross, who each made quite a name for himself as part of the mind-expanding hard SF movement that dominated the field back in the Mid-Nineties to the Naughts.

Here is the ad copy about the anthology:

The universe shifts and changes: suddenly you understand, you get it, and are filled with wonder. That moment of understanding drives the greatest science-fiction stories and lies at the heart of Engineering Infinity. Whether it’s coming up hard against the speed of light – and with it the enormity of the universe, realizing that terraforming a distant world is harder and more dangerous than you’d ever thought, or simply realizing that a hitchhiker on a starship consumes fuel and oxygen with tragic results, it’s hard science-fiction where a sense of discovery is most often found and where science-fiction’s true heart lies.

As for my story itself, here is a nod from a Mark Watson at Best SF:

Godlike powers at play from Wright, in his usual intense style. It’s a complex story, densely written and at time boggling, of human frailties and emotions exposed by those powers, it’s hard SF mashed up with epic Greek legend, reading almost as if translated from ancient stone tablets.

Another comment, gathered more or less at random from the Flotsam of the internet:

The only thing I’ve read by him since his conversion is the short story “Judgement Eve” from the anthology ENGINEERING INFINITY. It’s a good read in it’s way but definitely shows the influence of his present worldview. But it’s still well-written and, personally, I find it worthwhile to read the works of those whose beliefs I strongly disagree with.

I salute any soul noble enough to read and render fair judgment on a works by folks he finds personally distasteful. But I will not bother linking to this source, merely because I do not wish to embarrass the poor fellow. Definitely shows the influence of my present worldview, does it?

The story was written years before my conversion. It sat in my desk drawer for a decade before I found a market for it. High-concept Hard SF written in a lyrical, mythopoetic style is harder to place than one might imagine. Thank heavens for Jonathan Strahan.

Without giving away the surprise ending, it is a retelling of the story of the Flood of Noah where the angels of God are all Bad Guys. So if any man can read the yarn and somehow think this is post-conversion Wright, pink-faced with Papist zeal, working a sneaky bit of Narnia-style apologetics into his Hard SF, all I can say is that the muse works in mysterious ways, and that some men see what they want to see. Especially if they do not look.

Let this be an object lesson to all English majors or drive-by reviewers, who think they can puzzle out a writer’s soul by looking at the carven masks and costumes of our puppet-shows.

Writers are a tricky lot, and sometimes an element is present in the story because the divine muse with eyes of flame appeared in a dream and said to put it in. Or the editor said to put it in. Or the editor’s parole officer, his children, or his pet monkey, who was wandering by the office that day, and jumped up to his computer when no one was looking. (I believe the latest STAR WARS movie was edited almost entirely by pet monkeys.) Or sometimes a story element enters our world because we are cribbing like mad kleptomaniacs from the work of older and better authors.

In this particular case, the author from whom I am cribbing is Lord Byron. He is hardly any sort of Christian apologist, and, if the historical record is accurate, he was a shadow-vampire from the Negative Zone, who seduced maidens and drank their blood.

If you look up an obscure stage play he once wrote, called HEAVEN AND EARTH, you will see the same plot and story elements. All I added was nanotechnology.

Here is a sample to whet your appetite:

JUDGEMENT EVE

Imagine the boulevards of Golgolundra on the world’s last day, and the angels circling like vultures above it. Everywhere is noise, and lights, and gaiety, and crime, and chaos.

Imagine every wall and window of the crowded towers colorful with graffiti. The graffiti of these times are bright, not sloppy, composed of computer-assisted images of artistic depth and merit. They move, they sing, they speak to passers-by, and some of them reach from their billboards and kill whomever seems dispirited, obnoxious, dull; tiny flicks of paint flying up, reforming in mid air into blades or poisoned plumes of gas.

Other people, beautiful or monstrous or both, dancing in the street in their fantastic costumes, applaud and cheer when some vivid near-by death splatters them with blood. They do not wish to seem dull. The whole city screams and screams with laughter.

Why this forced gaiety? Why this hideous display? To-day is the birthday party for Typhon, their founder; today is the wake for mankind.

To-morrow the angels drown the world.

The streets are a festive combination of war-zone and mardi-gras.

Imagine most of the crimes are committed by the young, who are more extravagant. A shy young boy sees a laughing woman sway by, surrounded by handsome admirers raising glasses of Champaign and poison. It takes him but a moment to program his assemblers. A diamond drop, unnoticed, stings her flesh or flies into her wine. A moment later it has taken carbon from her blood to construct a series of gates and interrupts along major nerve- channels in her spine. The programming is precise and elegant, there is no jerkiness as her arms and leg muscles move, stimulated without her control. She tries to cry out for her companions. Instead, her lips move, she hears her voice make clever excuses, and away she walks with the shy boy. He becomes a shy rapist, perhaps using his controllers to overload her pleasure centers of her brain, or pain centers, before doing whatever else to her his bored imagination might conceive.

Or imagine a laughing woman, irked by an unwanted stare, or prompted by real fear, who programs her assemblers to shoot into the boy’s flesh, so that, in mid-festival, surrounded by unsure giggles, he will fall, his arms and legs distorted into clumsy lopsided shapes, or boneless tubes of flesh, while he stares in horror at the grotesque growths sprouting up from what was once his groin.

And perhaps she does not know who has offended her. Without sumptuary laws, faces and bodies change from day to day like images in nightmare. Better, she thinks, to program all assemblers to reproduce and strike at random. Any flesh they enter, check for genes. Spare those who carry XX chromosomes.

Now imagine, not two such folk, but a city of such people, creatures of godlike power and infantile rage. The sky above Golgolundra is dark with brilliant diamond points, thicker than confetti, a blizzard, and by now no one can tell who sent them out, or when, or why, or what their original programs were.

And where the assemblers fight each other (which they do often) the reaction heat from their rapid molecular manipulations starts fires in the city. No one fights the fires.

More people would be dead, more horribly, were it not for the Invigilators. They soar in the high pure air far above, surrounded by rainbows and rings of force.

Their technology is very different from that of the earth.

When they dive, manlike shapes can be seen, faces and forms of ruthless beauty. Their personal shields clothe each one in a radiant nimbus of gold, and the forces which give lift to their flying-cloaks make their wings to shine. Where the nimbuses sphere their heads, the glancing light makes golden rainbows appear and disappear.

Their faces are inhumanly perfect and stern. The mental training systems brought by the Ship of the Will give each one a perfect calm and utter sanity; the calm of a frozen winter pond.

Is it any wonder men call them angels?

From their eyes dart slender rays, like a warship’s searchlight, sweeping back and forth, penetrating crowds and clouds and hidden places.

Where they glance upon weapons or explosives, or fighting machines, they squint, and the rays of light tremble with mysterious force, and consume what they see with fire.

Sometimes the weapons, before they are found, discharge a futile shot or two toward the angels, whose shields flare to higher energies, flashing like whirlwinds of fire. People applaud when this happens.

Imagine Golgolundra. Everyone laughs. No one is happy. Everyone is doomed.

There was one young man among the dancing crowds who does not dance. He dresses in black and did not laugh. He is not doomed. And, perhaps, he has a chance, if small, to become happy.

In his forehead glints a ruby gem. Any passer-by with the proper machine can read his thoughts. The grim look on his face saves them the effort; his thoughts are clear.

The crowds part when he walks by. The dancers fall silent. The graffiti images recoil and do not molest him.

He is Idomenes, son of Ducaleon. His genetic modifications are not the same as those who live in Golgolundra. He is a Promethean; they are Typhonides.

He comes to the central tower, which serves Golgolundra as administration, rebellion-center, entertainment capital, and whorehouse. Idomenes paces down the wide corridors, looking neither right nor left. The monstrous statues, grotesque murals, or weeping deformities in their glass cages do not attract his attention.

Out from his black cloak, black diamonds fan out, sweeping the corridors before and behind him like nervous soldiers or presidential bodyguards, edging around corners, darting near anything suspicious, maintaining their spacing and their overlapping fields of fire. He ignores all this motion. He walks.

When he comes before a certain door, perhaps is was impatient with precautions. The swarms of black diamonds flutter back beneath his cloak, or come to rest in jewelried patterns along the chest and sleeves of his dark doublet.

The door recognizes him, and, without a word, politely opens.

Lounging at ease on a day-bed on the balcony, dreamily watching the distant fires, a woman of haunting beauty reclines. Her skin is the color of coffee with cream, her hair is as black as the midnight sea. She wears it very long. When she stood, it would fall fragrantly past her rounded hips and brush her shapely calves. When she lay on her stomach it was long enough so that, even when braided, it could be used to tie her wrists and ankles. When she lay on her side, as she did now, it formed luxurious cloud-scapes, and fell, little waterfalls, from bed to floor, stray locks swaying.

Above the couch floats a mirror. She watches the little glints of her white assemblers caressing her body. Where they pass, a garment of black lace is being woven tightly around her curves. The garment has no seams, and would have to be unwoven to remove it, or roughly ripped off.

She pretends she does not see she was being watched. Now she stretches and yawns like a cat, arching her back and moaning. She turns on her stomach, and regards Idomenes with mock- surprise. Her eyes are half-lidded. Her frail lace garb is half- woven.

He does not remove his gloves, but, at least, he holds his hand at his sides, and makes no gestures.

Idomenes speaks first, grand with simplicity. “Lilimariah, I want you to come with me to the stars.”

Lilimariah smiles mysteriously, as if charmed by distant music. Her voice is husky and low: “Men want only what they can’t get. That is the nature of desire.”

She stirs and half-arises, so she is leaning on one arm. Her hair is electrostatically charged, so that it floats and sways as if in a breeze, even though there is no breeze. “A lot of people would like to go to the stars, sweet lover. The angels won’t let them. All but your folk. The sheep.”

“I broke an oath to tell you these things. Do not mock my people. They will be saved.” Idomenes speaks harshly, stepping forward. Now he is close enough to smell her perfume, and his expression weakens into confusion and anger. His eyes burn like the black diamonds glittering in his coat.

She makes a swaying, supple motion of her naked shoulders, perhaps intended as a shrug. “What do you have that the angels want to save? Some pretty angel-lass fall in love with you?”

The muscles twitch in the corners of his jaw. “You mock them too? When the Ship first came from the stars, She saved us from the devastation of the Wars. We begged Her to govern and guide us. The Ship showed us how we might remove all the vicious old structures from our brains and genes, madness and rage and panic and hate. The Ship made the Invigilators to show us how it was done. Were we grateful? Did we learn? Did we listen?”

“‘Invigilators’? How quaint. You’re so old-fashioned some times, lover. We call them angels of death.”

“Do you think they want to kill? How many chances did we get? How many wars did we start, after how many warnings? How many people of the sea did we obliterate?”

“‘Dolphins’. We call them ‘Dolphins.’ And there were complex reasons for the genocide-wars. Economic reasons and stuff. Turmoil. And why did the Ship make them members of the Galactic Will when humans were kept in protectorate status? Them! Them! We made them! And now we were second class citizens!”

“‘Complex reasons’? Rage and jealousy and race-pride. Explain the complex reasons for the extermination camps and torture circuses.”

“They were cutting into our trade with the Ship!”

“Maybe they were richer because they didn’t kill each other all the time. As your people did mine. Was there a complex reason for that, too? Or was it just an expression of the rage and aggression your people will not remove from your brain-stem structures?”

“Some people think evil has survival value.”

“It is the purpose of the Law to see that it will not.” He speaks in a voice of dark majesty.

“Don’t lets argue politics again!” she pouts. “That’s all ancient history.”

“Fifty years ago is hardly ancient.”

“We never did anything to deserve this. No children!”

“The Ship sent a barrenness to all our women, yes, and sent plagues to sterilize the men, but that was for mercy’s sake. There were to be no children when the world drowned. And now that Typhon’s coffin was found and thawed, and he grew the last few weeks to become a man, it is done. There are no children left. No innocent lives. Today is Doomsday Eve! The hour is come!”

“And why are you here, lover?” she pouts and tosses back her head. “I hate long goodbyes. They bore me.”

“I’ve come to save you. My love for you burns like a devastating fire. It conquers my will and heart and sense and soul! You are the fairest child of a condemned and evil race, but I cannot believe, and I will not, that such beauty hides a soul wicked past cure!”

His eyes are narrow slits of fire. Now he steps forward and seizes her fragrant shoulders with his hands. Some of his assemblers, misunderstanding the sudden gesture, fly up to either side and hover like wasps; a sight of terror. But either her nerves are steel (a common replacement) or she is drowned in hysteria. She throws back her lovely head and laughed.

“Stop laughing! You must want life! You must want my love! Such love as mine cannot go unanswered! It dare not.” Then, more quietly, he says: “I will defy the Invigilators. They will be convinced by the force and ardor of my soul! If– if you were my wife — do you see what I am offering? — If you were a member of my household, the angels would not let me leave you behind!”

She gives him a cool, remote stare, her perfect lips hovering on the hint of a smile.

He steps back, deflated. As he draws his hands down, the deadly assemblers drop close to the floor and draw back.

Idomenes says, “Why this coldness? Tell me what you want.”

She is on her hands and knees, her fingers knotted into the silken fabrics of the bedclothes. Lilimariah keeps the same small half-smile on her lips, but she trembles when she speaks: “I want to be forced. Kidnap me. Kill my father, burn his house. Take me by force. Take me.”

“What a horrible thing to say. Are the angels right about us?”

She laughs. “That way I can’t be blamed. Don’t you understand women at all?”

“Sane women, I do.” Idomenes looks at her oddly. “Are you drunk? Have you been intoxicated against your will? There may be neuro-operators interfering with your brain-chemistry.”

He raises a finger and points at her. A black diamond flickers up from the floor, ready.

She screams, writhing backward. She is on her feet near the railing, perhaps ready to fall or jump.

He raises his hand, spreads his fingers. The black diamond falls back.

“Don’t you dare interfere with my body!” she shouts.

“What is it– ?”

Silently, softly, she says, “I’m pregnant.”

He says, dumbstruck, “No woman can be pregnant. We can make children artificially. The assembler technology was first made for that. But no one but the angels know what codes they used to force our biochemistry into sterile patterns…”

She says sharply, “Has it never occurred to the great Idomenes that there are assembler programmers better than even him?”

He snorts. “No. That thought I do not admit.”

Now she steps forward, hips swaying, her eyes glinting with danger and pain. “And has it never occurred to you that I might have another lover? One who can give me the child you cannot?!”

Idomenes steps back, as if he had been slapped. “I thought you loved me…”

“Why?”

“You said…”

“I say a lot of things.” She tosses her head.

“I thought it was that my father speaks with the angels; that my people were special, that you were attracted to my… my…”

“Your purity? Your righteousness? It is your worst fault.”

“You wanted my knowledge of assemblies, then. Is that it? You thought I could crack the angel’s code.”

Lilimariah folds her hands on her belly. Her head is bowed forward slightly, so that her hair falls about her like smoke. “There are needs a woman has no man can understand, and duties…”

He turns and leaves at this point, his face drained and hollow, his expression something more horrid than anger. The door does not open swiftly enough to suit him. He points, flicks his fingers, makes a fist. Black assemblers rearrange the wood into nitroglycerine compounds and blow the door-panels out of their frame. The shrapnel and smoke that strike him leave blood mingled with burns on his face, but his footsteps do not slow.

He does not hear the end of her sentence: “…duties even stronger than love.” Her hair hides her tears.

His assemblers re-knit his torn flesh and clean his skin before he goes down two corridors. He comes into an atrium. Here is what looked like a boy of eight or nine years, dressed as a harlequin, surrounded by a large flotilla of diamond assemblers.

Idomenes is in no mood to speak. He brings his hands together and makes a gesture. The Harlequin’s assemblers tremble and drop to the floor, dead, before any signal can move.

“Wait!” shouts the boy. “I’m not a Synthetic! I’m real! Killing me would be murder!”

Idomenes is pointing his finger, and his black assemblers, like a little galaxy, crowns upon crowns around him, hang in the air, ready. “All the real little boys are grown up.”

“I’m 21 to-day. I just made myself look this way because everybody hated me as I grew older.”

Idomenes lowers his hand. The black assemblers spread out and drop lower, idling on stand-by.

“You’re Typhon.”