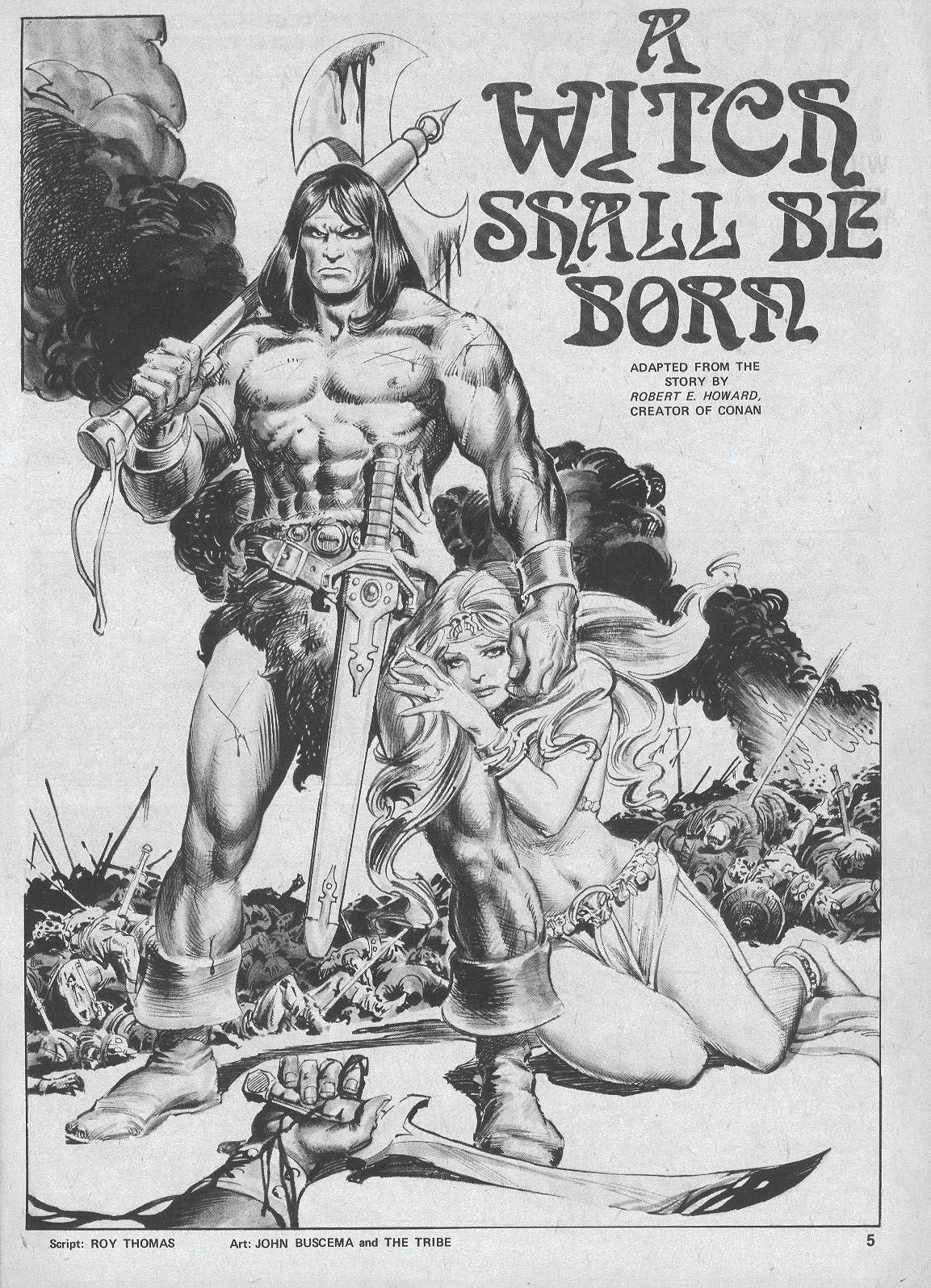

Conan: A Witch Shall Be Born

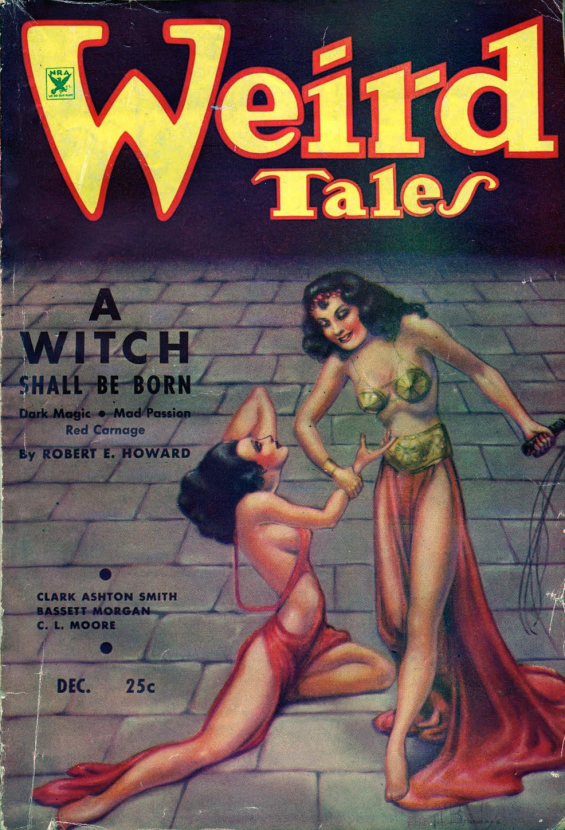

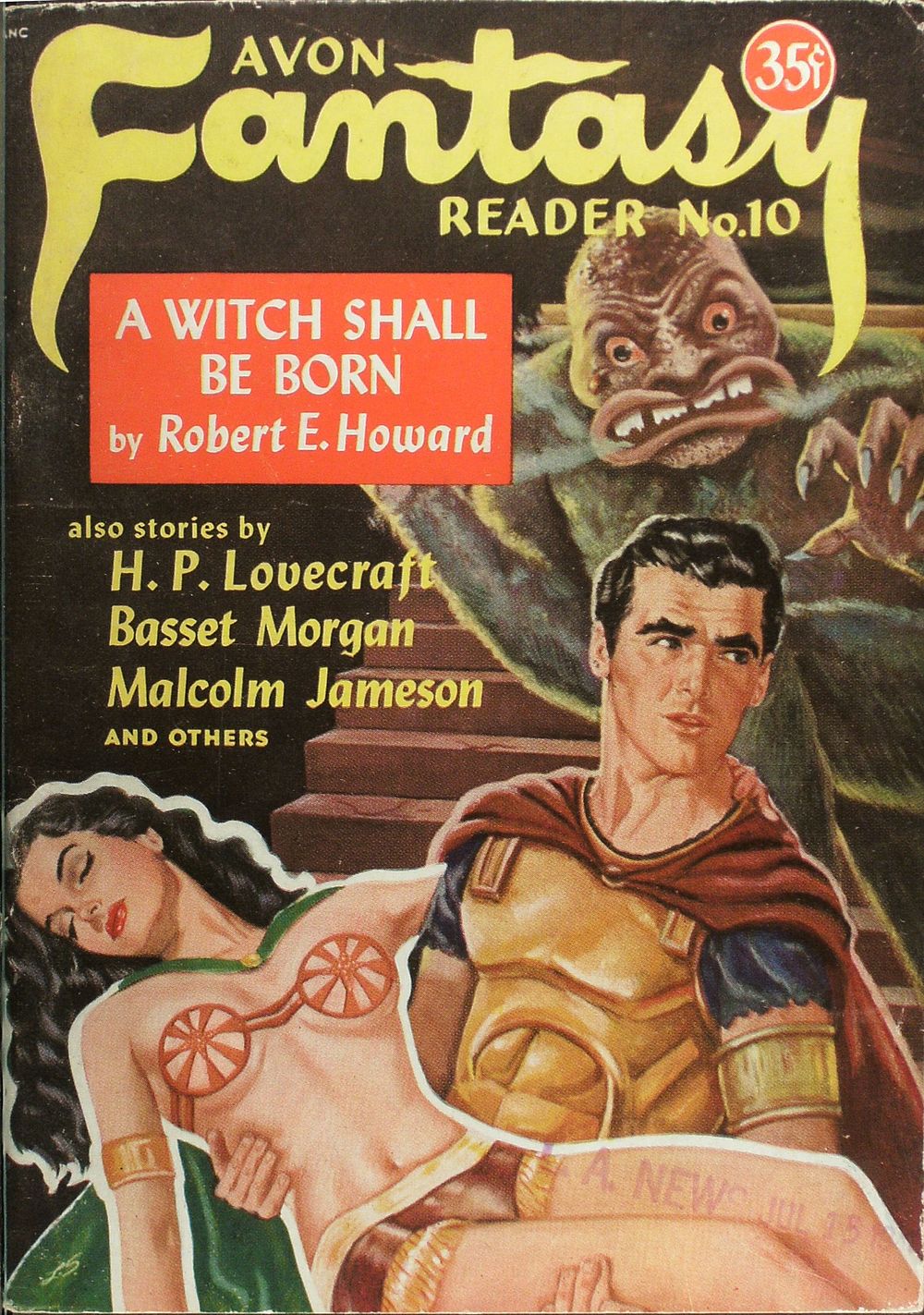

A Witch Shall Be Born was first published in Weird Tales magazine in December of 1934, coming one month after the final installment of People of the Black Circle. It is the thirteenth published story in the Conan canon.

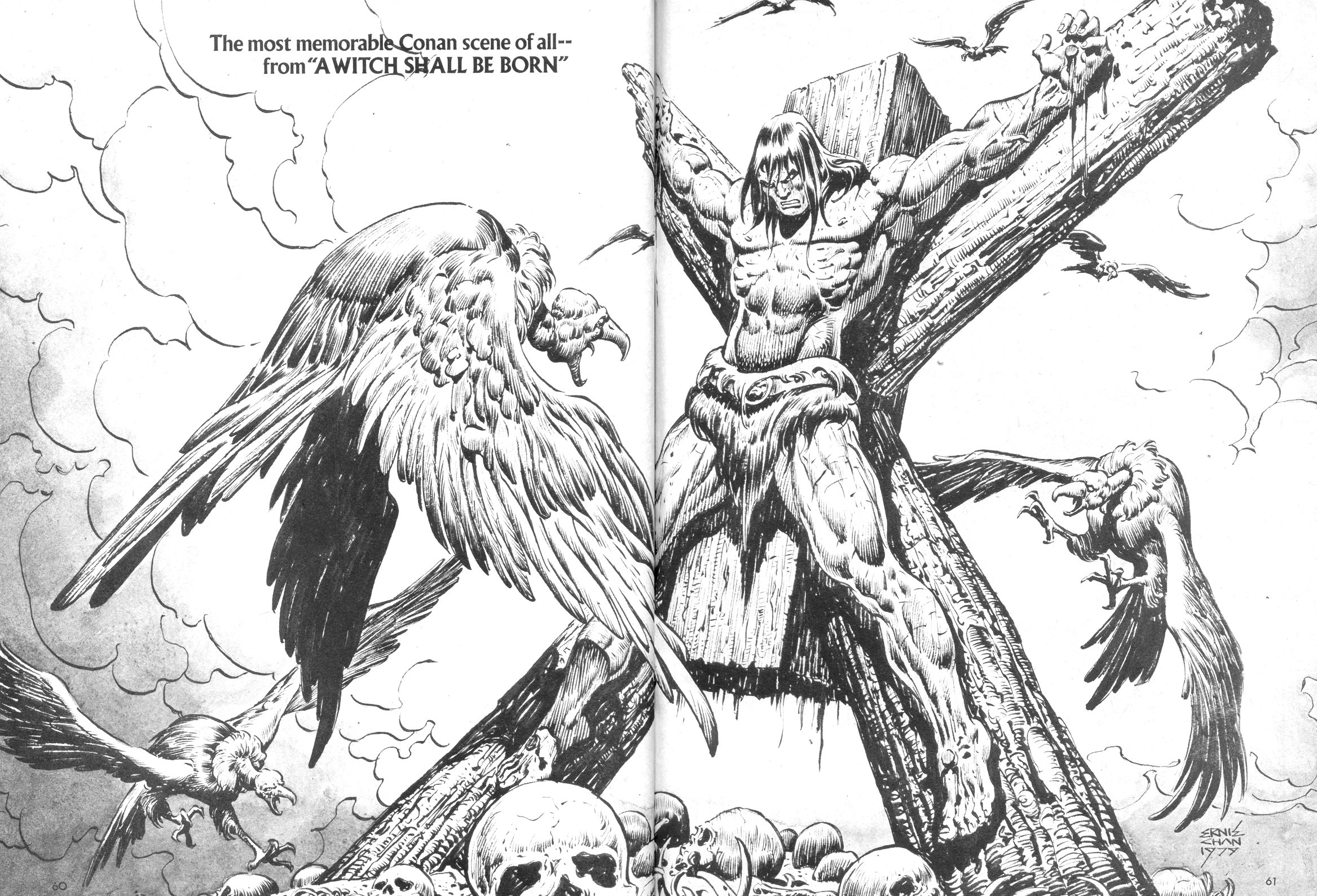

It is also, alas, one of the weaker and more forgettable Conan stories to spring from the masterful pen of Robert E. Howard, but, ironically, it contains one of the strongest and most memorable Conan scenes.

I have no doubt that every fan of Conan already knows which scene I mean. Since it is, perhaps, the best Conan scene ever, it was lifted wholly from the story and placed into the John Milius’ 1982 film CONAN THE BARBARIAN.

Nearly every element we have seen in previous Conan stories is present in A Witch Shall be Born. In that sense it is standard Conan fare:

Here we have a hot-blooded beautiful princess in distress, as was Yasmela in The Black Colossus who needs the help of Conan, who happens to be a mercenary captain in her service; a hot-blooded beautiful witch serves in the role of evil thaumaturge rather than Thoth-Amon (Phoenix on the Sword) or Tsotha (The Scarlet Citadel) or Yara (Tower of the Elephant); the two hot-blooded beauties fall into deadly rivalry, as did Thalis and Natala (Xuthal of the Dusk), complete with lurid scenes of the gorgeous half-naked damsel quivering and moaning in the dungeon; and he shapeless yet froglike eldritch menace from beyond space and time is here named Thaug rather than Thog.

Conan finds himself among wily but tough tribesmen, and rises to lead them, as in People of the Black Circle, and clashes in bloody battle with his foes.

What makes the story substandard is that all these familiar story elements, hitherto employed by Howard with a masterful strength and precision of a true wordsmith, are here cobbled together awkwardly and lifelessly.

The tale is a Frankenstein monster of body parts stitched together, but never struck with lightning, and never brought to life.

The tale opens in the bedchamber of Taramis the young queen, who beholds her doppelganger in the gloom, who describes drugging her maids and tricking her guards, and now will usurp her name, throne, life, and identity.

The evil twin sister is named Solome, who pauses to describe her cursed birth and abandonment in the fiery desert as a babe, her rescue by a magician of the Far East, one who is seeped deep in black wisdom, who raises her to womanhood. He trains her in the dark arts, but casts her away for being too lustful and passionate for the truly cosmic evil he serves.

Salome says:

I could never endure to seclude myself in a golden tower, and spend the long hours staring into a crystal globe, mumbling over incantations written on serpent’s skin in the blood of virgins, poring over musty volumes in forgotten languages.

I admit being amused by the concept of a witch who flunks out of her evil apprenticeship of evil for being too bored by book learning. It is explicitly said her master intended her to rule the world, but she wanted worldly pomp and power instead, and handsome paramours and a life of riotous harlotry. Party on, sexy witch!

Nothing comes of this concept here, and the event of her being driven away by her master is mentioned in passing, not described, not shown.

Then the two girls tell each other the political situation surrounding the city and known to both of them. Then the evil henchman, Constantius the Falcon, a mercenary leader loyal to the witch, enters the bedchamber to menace the young queen.

He actually pauses to twirl his mustachios, so we know he is wicked.

Noises from without reveal the city has been betrayed, and the gates opened to Constantius’ men. Taramis is to buried in an anonymous dungeon whose previous guards have all been poisoned offstage. She is condemned to endless wretched torment, but not before her womanhood is outraged in a fashion left to the reader’s lurid imagination. (Let it not be said that our grandfathers were less prurient than this generation; they were merely more delicate about when to cut away from such scenes.)

The next chapter introduces the hero of our story, the young and faithful soldier in the queen’s army, named something or other starting with a V. Valorous? Valiant? Something like that.

His wounds are being tended by his cooing but fearful girlfriend Ingva. Valiantius (or whatever his name is) is angry and baffled by the apparently betrayal of the city by its young queen to the mercenaries. One can forget these names immediately, because, aside from the two-word one-dimensional description (cooing but fearful, angry and baffled) these cardboard characters are forgettable.

I use the word “hero” advisedly here. It is Valeric (or whatever his name is) who discovers the witch’s secret, fights the witch’s men, kills the witch, and faces the monster, and rescues the girl. Twice.

Valerius talks to Ingva. The events of the exciting treason and bloodshed of the palace coup is described in summary.

Conan the Barbarian is now mentioned three thousand six hundred thirteen words exactly into a story allegedly about him. (I counted).

Conan is captain of the Palace Guard, was drunk the night before, but has such mastery of the men that when he orders his men not to obey the queen, they follow him. Conan roars, ‘This is not the queen! This isn’t Taramis! It’s some devil in masquerade!’

Valerius then tells Ingva:

“I never saw a man fight as Conan fought. He put his back to the courtyard wall, and before they overpowered him the dead men were strewn in heaps thigh-deep about him. But at last they dragged him down, a hundred against one.”

Well, for a one-line synopsis of a heroic battle that is not described, this is not bad; but it is forty words in a story already just shy of four thousand at this point. (I counted).

We cut immediately to the famous scene. You know the one I mean.

Now, at last, we get some characteristic Howardian prose:

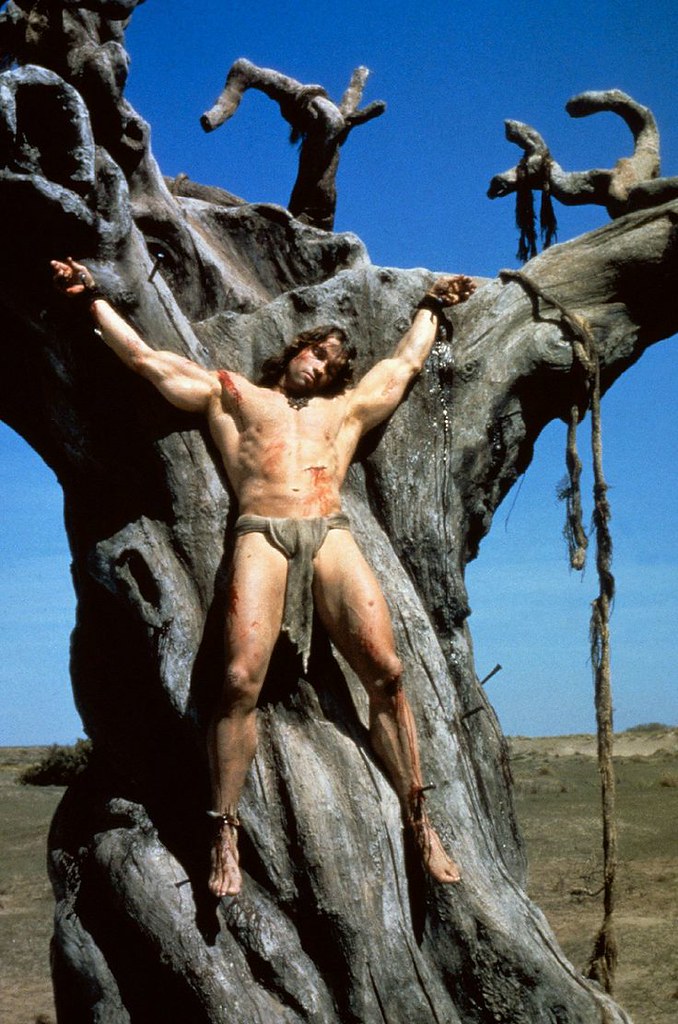

By the side of the caravan road a heavy cross had been planted, and on this grim tree a man hung, nailed there by iron spikes through his hands and feet. Naked but for a loin-cloth, the man was almost a giant in stature, and his muscles stood out in thick corded ridges on limbs and body, which the sun had long ago burned brown. The perspiration of agony beaded his face and his mighty breast, but from under the tangled black mane that fell over his low, broad forehead, his blue eyes blazed with an unquenched fire. Blood oozed sluggishly from the lacerations in his hands and feet.

Dang! This is what it means to be Conan. Blue eyes blazed with an unquenched fire. The words are stark and impressive.

Blood started afresh from the pierced palms as the victim’s mallet-like fists clenched convulsively on the spike-heads. Knots and bunches of muscle started out of the massive arms, and Conan bent his head forward and spat savagely at Constantius’s face. The voivode laughed coolly, wiped the saliva from his gorget and reined his horse about.

“Remember me when the vultures are tearing at your living flesh,” he called mockingly. “The desert scavengers are a particularly voracious breed. I have seen men hang for hours on a cross, eyeless, earless, and scalpless, before the sharp beaks had eaten their way into their vitals.”

Spitting defiance to the end! And a grisly end, worthy of nightmare. If you do not feel a chill or a thrill at this, gentle reader, be warned that Conan tales may not be for you, nor, perhaps, are any tales of shining swords and dark sorcery.

One has to pause to admire how adroitly Howard explains away that perennial question of villains who leave heroes alone to die. In this case, Constantius wants the vultures to peck and tear at Conan’s dying flesh, and so magnify the lingering agonies, and the vultures will not gather if guards, or any men, are near.

More description, equally masterful, of the hours hanging in the sun follow, the thirst, the terrible thirst, including the great barbarian’s thirst for vengeance. But he is dying. The merciless carrion-birds wheel lower. And then…

The vulture swept in with a swift roar of wings. Its beak flashed down, ripping the skin on Conan’s chin as he jerked his head aside; then before the bird could flash away, Conan’s head lunged forward on his mighty neck muscles, and his teeth, snapping like those of a wolf, locked on the bare, wattled neck.

Instantly the vulture exploded into squawking, flapping hysteria. Its thrashing wings blinded the man, and its talons ripped his chest. But grimly he hung on, the muscles starting out in lumps on his jaws. And the scavenger’s neckbones crunched between those powerful teeth. With a spasmodic flutter the bird hung limp. Conan let go, spat blood from his mouth. The other vultures, terrified by the fate of their companion, were in full flight to a distant tree, where they perched like black demons in conclave.

I lay my hand before my mouth.

The crucified man’s mastication the vulture stooping to peck his eyes is observed by a passing brigand named Olgerd Vladislav, the outlaw chief. He is impressed. How could he not be?

He is described as “once a hetman of the kozaki of the Zaporoskan River” For those of you who do not haunt old pulp magazines and lack a Lovecraftian vocabulary, a hetman is the military leader in the hetmanates of Ukraine, the Zaporizhian Host. Kozaki is the Ukrainian word for cossack. Zaporoska is no doubt inspired by the Zaporizhia, the territory beyond the rapids of the Dnieper River.

The whole cunning conceit of Howard’s Hyborian Age was that it was on the very fringe of historic times, so that the primordial ancestors of modern Slavs and Semites and Berbers and so on then existed, dressed and armed enough like their historical-era descendants to have the same exotic mood and glamour, but different enough that Howard need not fret over bothersome real-world details.

How else can we have a Persian princess’ evil sister raised by a Chinese diabolist enlisting Philistine mercenaries led by a Byzantine captain to fight Libyan horsemen led by a Cossack who saves a barbaric Irishman stronger than Cuchulainn nailed to a tree? And have a Lovecraftian monster claw its way into the final combat in the climax? No well-researched historical novel can get away with that. But prehistory is more generous.

If Howard himself did not invent the Rule of Cool (namely: “Reader tolerance for an unrealistic story-element is directly proportional to its awesomeness”) he surely is its best known practitioner, at least as far as this genre is concerned.

How and why Vladislav comes to dress and arm himself as a Zaugir tribesmen (read Berber) is nowhere mentioned, although surely his tale would be fascinating, were it told.

Vladislav decides to have his men chop down the cross, for he deems that if Conan can survive unaided both the bone-breaking fall and the hellish horse ride over blistering desert sands back to camp, the great Cimmerian will prove himself strong enough to be of use to Vladislav.

Any doubts remaining about Conan’s ferocious hardihood are quelled when, once one hand is free, he grabs the pliers and pulls the bloody spikes from his left hand and both feet himself.

We are next told that the savant Astreas, traveling in the East in his never-tiring search for knowledge, is writing a letter to his friend and fellow philosopher Alcemides. Do not bother to remember these names.

The prurient atrocities of Salome, living disguised as the fair and good queen Tamaris, are briefly described in this letter, and an entire seasons of raids, wars, battles and so on between Vladislav’s ever-growing band of desert raiders and the city guard of Tamaris is mentioned in passing. Tamaris has summoned up a monster frog demon from the abyss, to whom she feeds human sacrifices. None of this lurid bloodshed or torment or orgies of misbehavior is on stage.

The hate of Conan for Constantius is mentioned in the letter (In case you’ve forgotten, Constantius is the sadist who nailed him on the cross who ravishes imprisoned queens and twirls mustachios, see above.) Also mentioned is the inability of the desert raiders to mount a siege against the city without proper siege engines.

Next, we see Salome displaying a severed head to the half-naked Taramis in the dungeon to grieve her. It was the head of someone or other. She is grieved.

Then a spy pretending to be a deaf-mute beggar overhears Salome boasting to her henchman, and learns that the good queen still lives, and is in the prison. This spy turns out later to be Valerius, but the author forgets to include his name for at least two scenes.

Conan, meanwhile, is drinking in the tent of his savior Vladislav, to whom he swore fealty, and has been following these several months. The band has grown, as has the ambition of Vladislav, but Conan needs the band to work his revenge. So Conan casually betrays Vladislav, breaks his arm, but allows him to take a horse and flee with his life, after announcing that he has, off-stage, in a fashion not stated, won the loyalty of all the men following Vladislav.

Conan is now the leader of an army. This is the culmination of months of sleepless planning and singlemindedness as pure as that of the Count of Montecristo, except that the sleeping planning and patient work is all offstage, having already taken place, and, again, is mentioned only in passing.

There is not a single word or act mentioned to describe why the men loyal to Vladislav would switch fealty to Conan. He makes no speech, promises no loot, cows no defiance, displays no leadership. This is far different from similar scenarios in other stories, such as, for example, People of the Black Circle, or the Black Colossus, wherein the author takes the time to show us these things.

All plot threads combine in the final scene of war, when Vladislav’s band of men, now Conan’s, march on the city.

None of the battle is actually on stage. Not a single sword stroke of it.

Instead, Salome through a crystal ball hears a report from a thin acolyte in her service who has followed Constantius into war. The defenders had been smug in the knowledge that the desert nomads had no siege equipment to breach the massy walls; until sharp-eyed scout reports otherwise, seeing siege engines among the wagon train of the attackers.

Constantius has no choice but to sally forth and attack, but he is confident, because the light cavalry of the nomads cannot withstand a charge from his heavily armored horsemen. He has the advantage.

But then his men are is cut to bits by Conan’s vanguard, who are heavily armored knights. Indeed, these are the exiled knights of the true queen who fled the coup, and had been living as robbers themselves, now eager to return liberty to their home. The advantage of Constantius evaporates.

In a plot twist, the siege engines turn out to be a trick, mere frames of palm trunks and painted silk. Conan may be a barbarian, but he is wily as a fox.

Meanwhile, Valerius uses the opportunity of the confusion of the battle at the city gates, when all the men-at-arms are busy, to lead a desperate band of armed loyalists to storm the palace dungeon and free the real queen. The witch stuns him with a flash-bang grenade, and drags Taramis off to an evil chapel to be sacrificed. Ingva appears and helps Valerius back to his feet.

Valerius recovers his wits and rushes into the evil chapel, stabbing a knife-wielding evil priest, and carries the under-dressed queen to safety. He impales the witch through the heart, but not before she unleashes the horrific frog monster from the pits below the palace, the monstrous Thaug.

Thaug is not to be confused with the other horrific frog monster from another story, Thog (Xuthal of the Dusk). The difference between the two monsters is that Thaug is not sufficiently described to be eerie, or spooky, or seem a danger, whereas Thog was all these things. The monster here is, in fact, more like a placeholder or a jotted post-it note were the author should have gone back and put a monster into the text.

Valerius and the rescued queen flee from the monster but are trapped between it and the evil guards, when Conan arrives with his cavalry, having overcome the city defenders offstage. The climactic battle between Conan and the primordial horror of froggy evil consist of this:

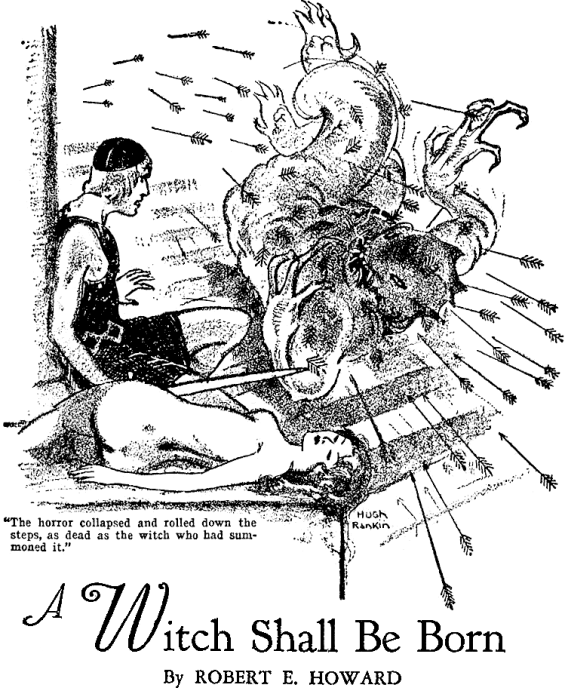

Conan yelled a command. Without checking their headlong pace, the desert men lifted their bows, drew and loosed. A cloud of arrows sang across the square, over the seething heads of the multitudes, and sank feather-deep in the black monster. It halted, wavered, reared, a black blot against the marble pillars. Again the sharp cloud sang, and yet again, and the horror collapsed and rolled down the steps, as dead as the witch who had summoned it out of the night of ages.

This is the very definition of anticlimax.

Conan then nails Constantius on a cross to die, and mocks him for being weak.

The end.

Making Valerius the hero of a Conan tale is incomprehensible gaff of the craft of writing. Structurally, there are two stories here: the witch replacing Tamaris, and Valerius rescuing her; Constantius crucifies Conan, who escapes the cross, executes an exact revenge. They have no overlap.

Had I been Farnsworth Wright, my editorial suggestion to Mr. Howard would have been to tie the two threads more closely together: have Valerius, not a passing Cossack, rescue Conan from the cross in a desperate night venture, let them exchange vows of blood brotherhood, so that both are working to avenge themselves on Constantius and the witch-queen, one inside the city, the other by raising an army from the exiles and the desert raiders.

A scene of human sacrifice should have been on stage, or some depiction of the evil of the witch, aside from snippy dialog with her sister. Also on stage let there be some of the spy work by Valerius to determine the queen’s location.

More to the point, it is awesome that Conan knows from the first that Salome is not the real queen, but the text never credits his wolf-sharp barbarian instincts (or whatever) and Valerius never decides to trust Conan’s unsupported word in an impressive act of faith in Conan.

Meanwhile, Conan should have been shown winning the loyalty of the erstwhile enemy nomads of the desert, so that the reader sees, rather than being merely told, that a barbarian understand a tribesman better than would a Cossack.

Also, there should have been at least one fight scene on stage, and it should have involved Valerius and Conan fighting back to back against overwhelming odds, or, at least, coordinating their efforts.

Instead the two men each act alone. Hence it is a jarring note when, immediately upon being rescued by Valerius, who carried her unconscious body up and down corridors and stairs fleeing a giant toad monster at their heels, the fainting queen wakes, whereupon, for no clear reason, Conan, not Valerius, doffs his cloak like a gentle and civilized man to throw over her naked body, Conan not Valerius, receives her thanks and praise, and Conan, not Valerius, is offered the post not only of captain, but of Queen’s Councilor as well.

Had Valerius then and there whipped out his misericorde and plunged it into the Cimmerian’s black heart for stealing his thunder and taking credit for all the youth’s brave deeds, this reader, at least, could not have called it unjust.

Instead Valerius sweeps Ingva into his arms to win from her the lingering kiss that culminates all good romances. If the reader has forgotten who Ingva is, this is because she has no personality and serves no purpose in the plot.

The theme that runs through all Conan stories, namely, of the superiority of the noble savage above the corruptions of civilization, is here somewhat muted. I see only one mention of it, and, since it comes from Conan’s own mouth, it comes across as a trifle self serving. He mocks the crucified Constantius, the Desert Falcon:

“You are more fit to inflict torture than to endure it,” said Conan tranquilly. “I hung there on a cross as you are hanging, and I lived, thanks to circumstances and a stamina peculiar to barbarians. But you civilized men are soft; your lives are not nailed to your spines as are ours. Your fortitude consists mainly in inflicting torment, not in enduring it. You will be dead before sundown. And so, Falcon of the desert, I leave you to the companionship of another bird of the desert.”

I am a great admirer of Howard’s purple yet curt and manly prose: usually, his pen can conjure a sharp, clear picture in all its brutal earthliness or eerie unearthliness with a vivid turn of phrase. In this tale, however, Howard prefers to have most of the tale offstage, and the events conveyed in monologue from one character to another.

The only points at which Howard allows his pen to flame into full power are the two scenes in which Conan appears: his cruel crucifixion, and his cruel betrayal of Vladislav.

If a tutor of the craft of writing wished a clear example of the rule that the prose should ‘show, not tell’, the events in a tale, then A Witch Shall Be Born is the finest example possible of what not to do.

Lest your humble author be mocked for criticizing a master more skilled than he, allow me to say that yours truly has also, from time to time, fallen into the habit of reporting important scenes second hand. Having made the mistake myself, I know of what it consists.

When it is done right, the viewpoint selected put certain story elements in the foreground or background that shed a different light, or bring out a different angle, than expected. In a true masterwork, for example, Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 film Rashomon, an entire story can be built out of telling the same scene from multiple viewpoints, to potent effect.

In other words, the rule of ‘show, don’t tell’, is a simplified version of the true rule, which might be phrased, ‘show, don’t tell, unless telling shows more.’

Usually, such hearsay scenes or epistolary stories attempt the clever trick of telling the reader the events while simultaneously developing the character doing the telling. We readers discover not only the narrated events, but learn, by what he narrates and how, the traits of the teller. He has a particular voice and vocabulary and viewpoint.

A writer seeking to hone his craft could, for example, should be skilled enough to have a male character tell a scene from his viewpoint, and a female recount the same scene from hers. If the writer cannot distinguish the two voices, even if both recount the same events, the writer either needs to learn more about writing, or more about the opposite sex.

Imagine the difference, for example, in how Long John Silver from Treasure Island would explain the events in the myth of Orpheus versus, let us say, Lucifer from Paradise Lost. “Aye, ’twas a bad bit of bizness, that, when the cully were but one wee step from the shinin’ light o’ day, when he had to peak athwart his shoulder aftwise, and spy the ghost of his wench what followed him! The fool!” as opposed to “Then did the jealousy of the tyrant in heaven, secure in his cloudy throne imperishable, with pitiless hand snatch away the pale beloved shadow of the bride of the singer of songs, which turned then forever to such dolorous note as the high empyrean hears not, nor heeds. His weeping eye her no more did behold forever.”

But, in order for this bit of writing craft to work, the diagetic narrator has to be a character, that is, he has to have a personality, or the letter he pens has to serve some function in the plot, or something.

Imagine the difference between an unknown scholar writing another unknown scholar about the events of the city, as opposed to, let us say, a desperate letter from the rebel leader Valerius begging for help from a neighboring king; or else, let us say, a gloating letter from one of the spies of Vladislav the robber king, telling his master of the weakness of the city now that occultism and corruption rule the streets, making it vulnerable to his planned attack.

Or, if the letter must be written by the savant Astreas, in his mouth should go the information Salome relates to Taramis about her own accursed origin and destiny, information a scholar might know, but Salome could not:

“Every century a witch shall be born.” So ran the ancient curse. And so it has come to pass. Some were slain at birth, as they sought to slay me. Some walked the earth as witches, proud daughters of Khauran, with the moon of hell burning upon their ivory bosoms. Each was named Salome. I too am Salome. It was always Salome, the witch. It will always be Salome, the witch, even when the mountains of ice have roared down from the pole and ground the civilizations to ruin, and a new world has risen from the ashes and dust—even then there shall be Salomes to walk the earth, to trap men’s hearts by their sorcery, to dance before the kings of the world, to see the heads of the wise men fall at their pleasure.”

Since Salome was kicked out of Slytherin for her lack of book learning, it is jarring to have her know of all these previous incarnations, or to prophecy her own future incarnation to come. Because the author is here establishing that this is the selfsame Salome, or at least a girl of the same name born of the same curse, who danced for Herod the Great, and demanded the head of John the Baptist in a charger.

This is not the only borrowing of Biblical themes and images in this story, one must note.

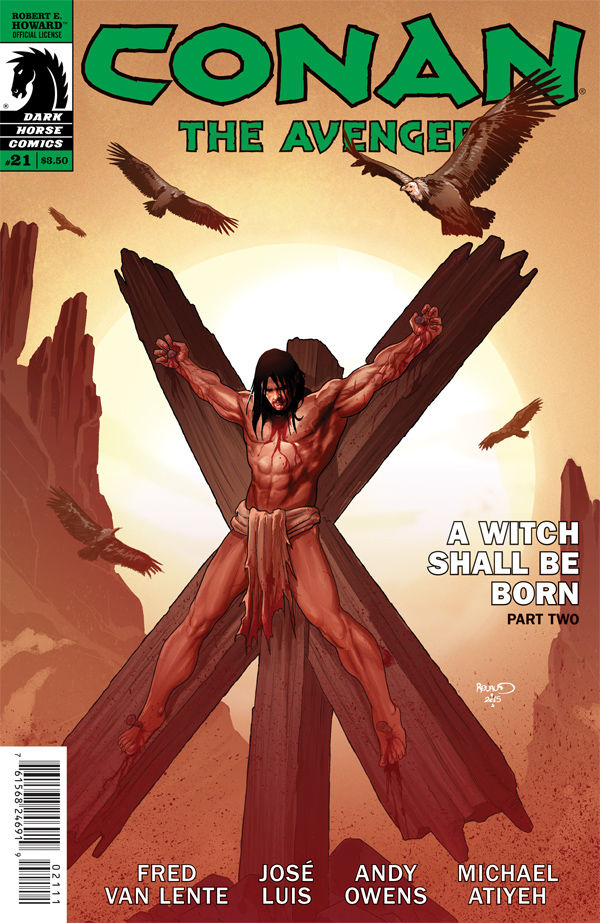

The crucifixion on the cross, while it was a common enough punishment in Roman times for slaves and traitors, is relatively rare in the realms of fantasy stories. First, this is because it is a grisly death, one of the most if not the most sadistic ever devised by the twisted mind of man. Second, of course, is the danger to the storyteller that if you hang your hero on the cross, the reader might unwittingly be reminded of another and greater hero hung on a cross, and the contrast cast a bit of shade on your own invented protagonist.

In writing this series of columns, your humble author has never had the least trouble finding illustrations to adorn the tales being reviewed, because there are ninety years and counting of continuous reprints and adaptations of each story. I have never had hitherto the least trouble finding illustrations or more than one, depicting precisely the scene in the text.

However, without exception, all the depictions of the crucifixion scene had one inaccuracy in common.

In all of these, including the film version, Conan is either crucified on a tree, or on the cross of Saint Andrew. However, from the text, since the cross is chopped down by one axman and not two, that the author intended the traditional cross.

And it is the Cross of Christ on which Conan hangs, because his arms are not tied in place. Nor are the nails through his wrists, as the Shroud of Turin shows the real nails of the real Christ went through. As best we know, a nail through the palm could not support the weight of a man. However, this is the almost universal depiction of the crucifixion of Our Lord in religious art, and, as far as I know, no one else is ever depicted as being hung in his precise way.

The illustrators, I might venture to guess, want to avoid the same unfortunate contrast into Mr. Howard stumbles, and not make the religious parallel so obvious.

Considering that Conan, in this tale, is as treacherous and callous and brutal he ever is, here the shade thrown on him by that contrast seems particularly dark.

Compared to other famous crucified people, Conan might be physically tougher than, say, Spartacus, but he is not here shown to be as good a leader of men, nor fighting in any cause more serious than his own understandable grudge.

Conan, meanwhile, is not physically tough enough to hang there until death, to get buried, and, after descending into hell, to defeat the kings of the inferno, to rescue Adam and the patriarchs and prophets, and then to come back in disguise to walk the road of Emmaus unrecognized. In this story alone, perhaps because of the reminder hidden in the Biblical imagery, it is sharply obvious that Conan is a villain, and not a very grandiose one.

Of course, Spartacus was not tough enough to kill a vulture with his teeth, so there is that.

This is the first Conan story I would recommend skipping, or, if one is a completist, read chapter 2 “The Tree of Death” and chapter 6 “The Vulture’s Wings.”

Everything else the reader needs to know can be summarized in a review column like this one without any loss, because, to be quite frank, the story itself reads like a summery.

This work still has echoes and hints of the good story it could have been had it been three times as long, and the scenes actually put on stage, and peopled by character the writer took the time and effort to develop.

I do not want to be too harsh. Often I have said that Howard on his worst day is better than most writers on their best day. But, as they say, even Homer nods, and A Witch Shall be Born is, unfortunately, is Howard on his worst day.