Conan: Beyond the Black River

Beyond the Black River was first published in Weird Tales magazine, serialized from May to June of 1935, the first part coming three months after Jewels of Gwahlur . It is the fifteenth published story in the Conan canon.

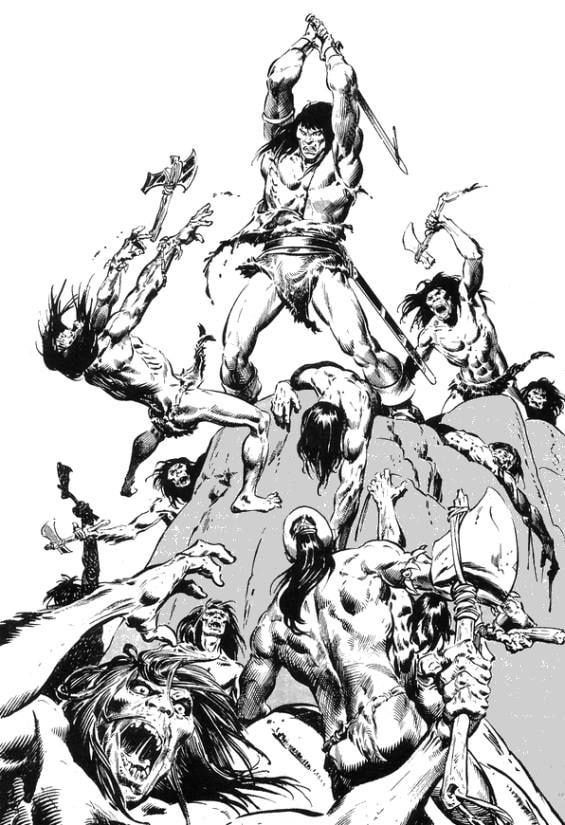

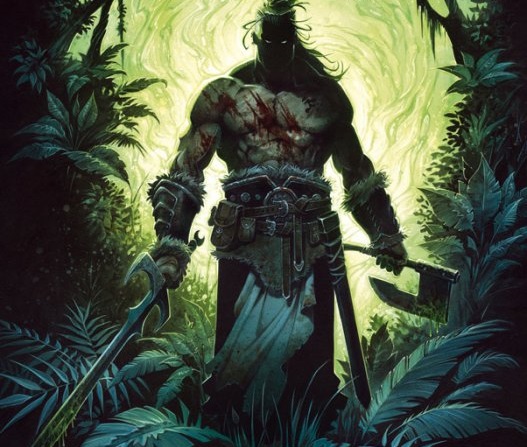

Conan here is once again the archetypal noble savage. The superiority of the grand and lonely barbarian, a man who prevails with no sort of civilization to aid or soften him, is once again clearly on display. Indeed, the quality is one that can be seen with the eyes, spotted before a word is spoken.

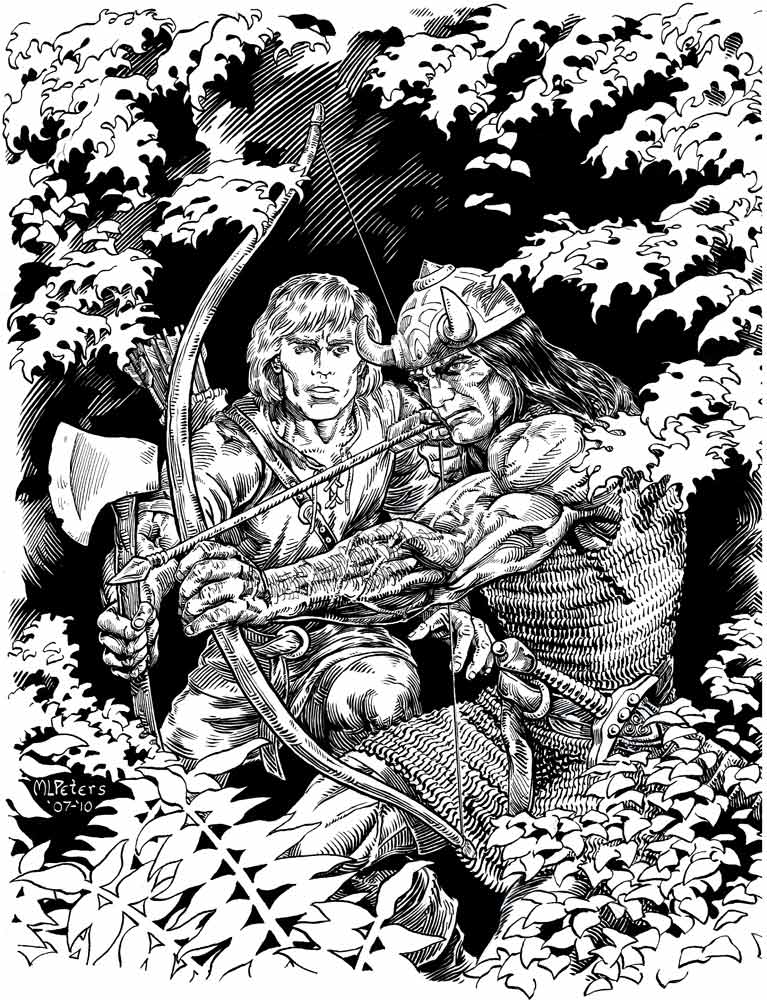

Thus is Conan described when he first steps into view on a path of a deadly forest.

… [Conan] wore a sleeveless hauberk of dark mesh-mail in place of a tunic, and a helmet perched on his black mane. That helmet held the other’s gaze; it was without a crest, but adorned by short bull’s horns. No civilized hand ever forged that head-piece. Nor was the face below it that of a civilized man: dark, scarred, with smoldering blue eyes, it was a face as untamed as the primordial forest which formed its background.

[Conan’s] massive iron-clad breast, and the arm that bore the reddened sword [were] burned dark by the sun and ridged and corded with muscles. He moved with the dangerous ease of a panther; he was too fiercely supple to be a product of civilization, even of that fringe of civilization which composed the outer frontiers.

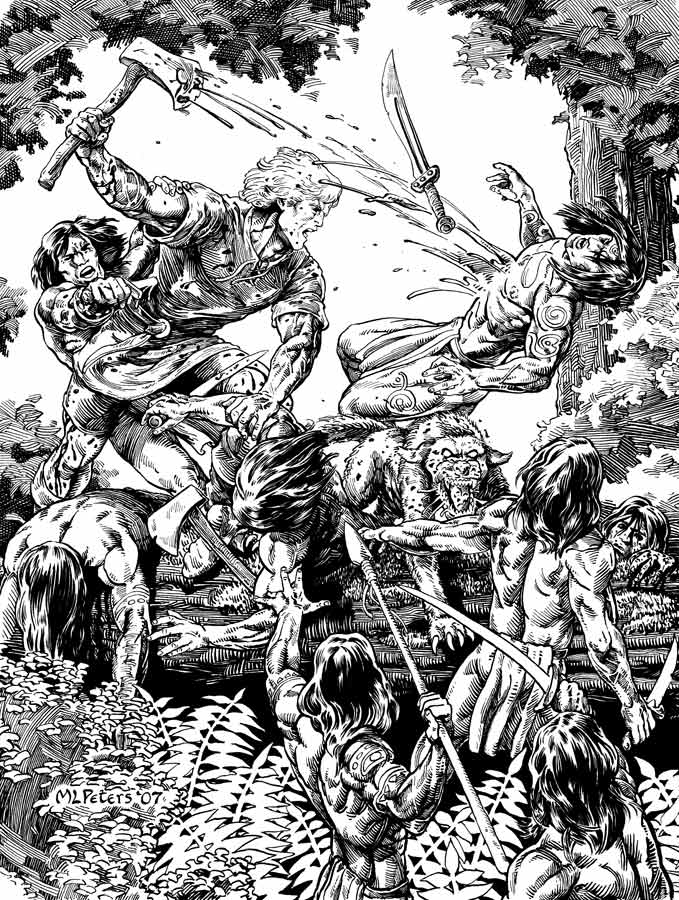

In the same way Pool of the Black One was a buccaneer tale, and People of the Black Circle was a tale of the Great Game in Afghanistan, so, here, we are suddenly thrust into a tale of the frontier days of Daniel Boone, with the Picts in the role of the Redskin braves.

Here is Conan the Indian-fighter.

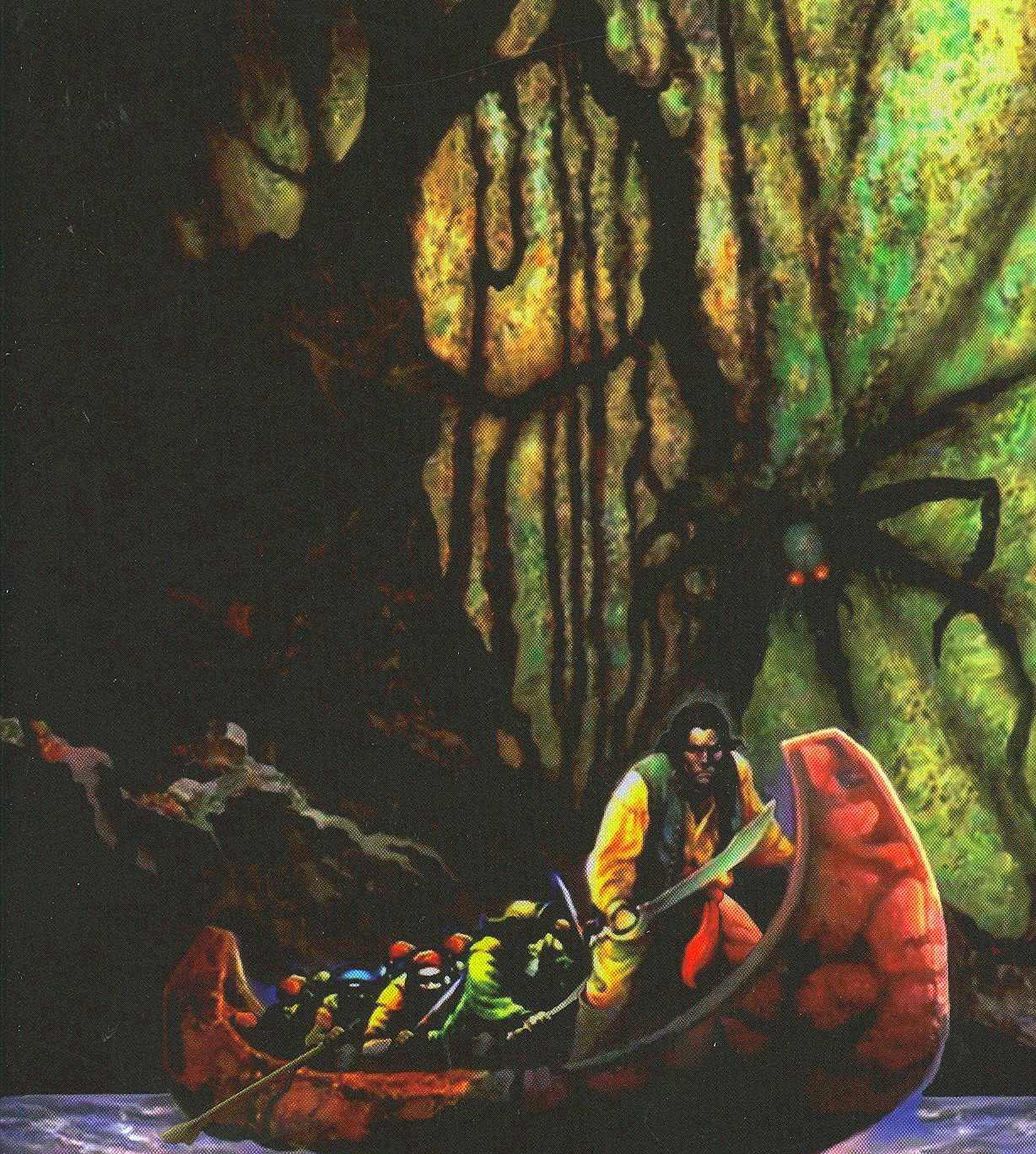

The plot is straightforward: the civilized men of the East have established a frontier fort to protect the settlers encroaching on the lands of the Picts, who are naked, painted tribesmen worshipping bloodthirsty beast-gods in their ancient, dark forests that have never known the bite of civilized axe.

A tribal wizard among the Picts, by his charisma and evil magic, has organized the thirteen tribes into a raiding force that threatens both homesteads and frontier fort, who are foolishly underprepared.

Conan, acting as a scout for the fort commander, too late sees signs of the coming raid, and races desperately through the pathless wood, pursued by devils and devil-worshipping braves, to warn the settlers.

By a grim irony, the savage shaman dies by the same magic by which he lived, and only Conan knows whose hand it was that truly slew him.

This is one of the longer Conan stories, but not one of the better ones.

There is nothing particularly wrong with it, but there a lack of the brilliance and energy seen in other tales. There is no strong driver to the plot, aside from the pretense of warning the settlers to flee, which has a moment or two of true drama. The ending is bitter, and the conflict described is in vain.

The tale, frankly, is wandering and a little long, and so, it is befitting to set here my observations in no particular order, wandering and a bit long.

There is no lack of action and adventure, and the fight scenes are depicted with the usual Howardian stark, savage vividness.

The silent and woodcrafty Picts make excellent and scary villains. Alas, our viewpoint character, Balthus, a young soldier, is forgettable.

But I do love the dog, Slasher, who is the stone-cold killer Lassie, faithful hound of the Hyborian Age. More on him later.

Conan, here, is as hard and curt as any cowboy from John Wayne to Clint Eastwood. As he heads out into the savage wildness with a group of scouts — all of whom die but one — he says to the fort commander:

“If we live, we should be back by daybreak.”

Perfect. Conan is not the only tough customers in the scene. The frontiersmen are thus described:

They dressed alike—in buckskin boots, leathern breeks and deerskin shirts, with broad girdles that held axes and short swords; and they were all gaunt and scarred and hard-eyed; sinewy and taciturn.

And their savage Pictish opponents:

Beyond the river the primitive still reigned in shadowy forests, brush-thatched huts where hung the grinning skulls of men, and mud-walled enclosures where fires flickered and drums rumbled, and spears were whetted in the hands of dark, silent men with tangled black hair and the eyes of serpents.

One character describes the frontier this way:

“We have dim rumors of great swamps and rivers, and a forest that stretches on and on over everlasting plains and hills to end at last on the shores of the western ocean. But what things lie between this river and that ocean we dare not even guess. No white man has ever plunged deep into that fastness and returned alive to tell us what he found.”

Between the time when the oceans drank Atlantis, and the rise of the sons of Aryas, was an age undreamed of — and it might seem an odd age in which to place the theme of a Cowboys and Indians yarn, with swords instead of sixguns, complete with eldritch wizards commanding unearthly forest demons, but actually it is the perfect age to put it.

The theme of the tale is stated explicitly from our viewpoint character, Balthus:

“We are wise in our civilized knowledge, but our knowledge extends just so far—to the western bank of that ancient river! Who knows what shapes earthly and unearthly may lurk beyond the dim circle of light our knowledge has cast? … Who knows what gods are worshipped under the shadows of that heathen forest, or what devils crawl out of the black ooze of the swamps?”

There does not seem to be enough room on whatever map one might imagine of the landmass of the Hyborian Age to accommodate a forest that stretches over everlasting plains and hills to the Atlantic. But on the other hand, the wilderness of Gaul and Spain surely were wild and large enough when seen through the eyes of Phoenicians or Romans.

Howard has our barbarian sage, Conan, dismisses the civilized greed provoking the colonial conflict with the natives as insanity:

“This colonization business is mad, anyway. There’s plenty of good land east of the Bossonian marches. If the Aquilonians would cut up some of the big estates of their barons, and plant wheat where now only deer are hunted, they wouldn’t have to cross the border and take the land of the Picts away from them.”

Our noble savage, as might be expected, is an egalitarian, and so would rather despoil the rich of their luxuries than despoil the Picts of their subsistence.

It is difficult now to recall, but Americans once had an ambiguous respect and pity toward the Indians defeated when the West was won: it was an admixture of admiration for the fallen foe, regret at the necessity, glory in the victory, all mingled with nostalgia and perhaps a note of compassion.

The exaggerated simplicity of the pretense of self flagellation over the issue, so common these days, washes out the finer, more nuanced, and more honest emotions present even in such early works as THE OREGON TRAIL by Parkman (1847), written in the years before the Civil War.

This ambiguous respect for the passing away of the old ways of tribal life is, of course, much the same theme the ambiguous regret of the civilized man for the laws, restrictions, and various inequalities and inequities of civilized life which is the soul and spirit of a Conan story, or any yarn that presents savage life as noble.

Back when we all lived in the woods, and every man not a member of your tribe and hunting band was an enemy, life was poor, nasty, brutish, and short, but, on the other hand, no one had to argue with bureaucrats about back-taxes.

It is an interesting parallel to compare this regret for civilization to the melancholy that informs the Lord of the Rings.

That work by Professor Tolkien, even from the first chapter, sees the passing away not only of the elves, but also of the orcs. The great glory of the elder days vanishes in the Third Age of Middle East, taking with it the horrors of the Dark Lord. The magic, both good and evil, is now forgotten. Relics once unutterably precious become “mathoms” — objects whose use is forgotten.

The nostalgia is the same, but what it is whose passing is to be regretted is very nearly opposite: the raw barbarism and honest savagery of the primordial ancestors, when each man relied on his own strength of muscle alone is on the one hand, and on the other, the shining towers and ancient virtues of a Catholic civilization before its downfall into modern routines of scientific warfare, industrial pollution, municipal overpopulation, cynical realpolitik, and the postmodern downfall into sick, shallow, dead-eyed nihilism.

Of course, in a Conan Tale, even if it is explicitly a frontier story where Davy Crockett would be at home, also must have some smattering of eldritch horror:

“The soldiers, who do not believe in ghosts or devils are almost in a panic of fear. You, Conan, who believe in ghosts, ghouls, goblins, and all manner of uncanny things, do not seem to fear any of the things in which you believe.”

Conan answers:

“There’s nothing in the universe cold steel won’t cut.”

A strange reverse anachronism here: the soldiers of primeval antiquity do not believe in ghosts or devils?

An outlandish thing to assume, considering how frequently devils appear in the Hyborian Age.

It would be as if a modern man were to say the police do not believe in unibombers or serial killers, or some other rare danger they are called upon to fight.

But Conan is the pragmatic materialist who believe that a ghost or devil, if it exists, must be made of matter, therefore prone to be cut with steel?

An outlandish thing to say for one whose own experience with invulnerable or immaterial apparitions in previous short stories shows this is not the case.

I note that this is the very reverse of what was established in the ‘The People of the Black Circle’ where the mere fact that men of the East were culturally and traditionally accustomed to superstitious belief in the power of hypnotism allowed hypnotists to hex them, whereas Conan, from the more skeptical West, was partly immune. But now the civilized men, because they do not believe in ghosts and ghouls, are dismissed as fools.

Treating magic as an alternate technology may have been a fresh and unusual idea back when Lyndon Hardy did it in MASTER OF FIVE MAGICS, or Bob Heinlein in MAGIC, INC – but it lacks the sense of the uncanny which magic, particularly black magic, is meant to evoke.

Conan never falls into this mistake. Magic is always occult, dark, treacherous.

Conan, at one point, uses a magic rune to escape a haunted beast set on his trail, but this stirs up the enmity of the spirit-creature whose name he uses in vain.

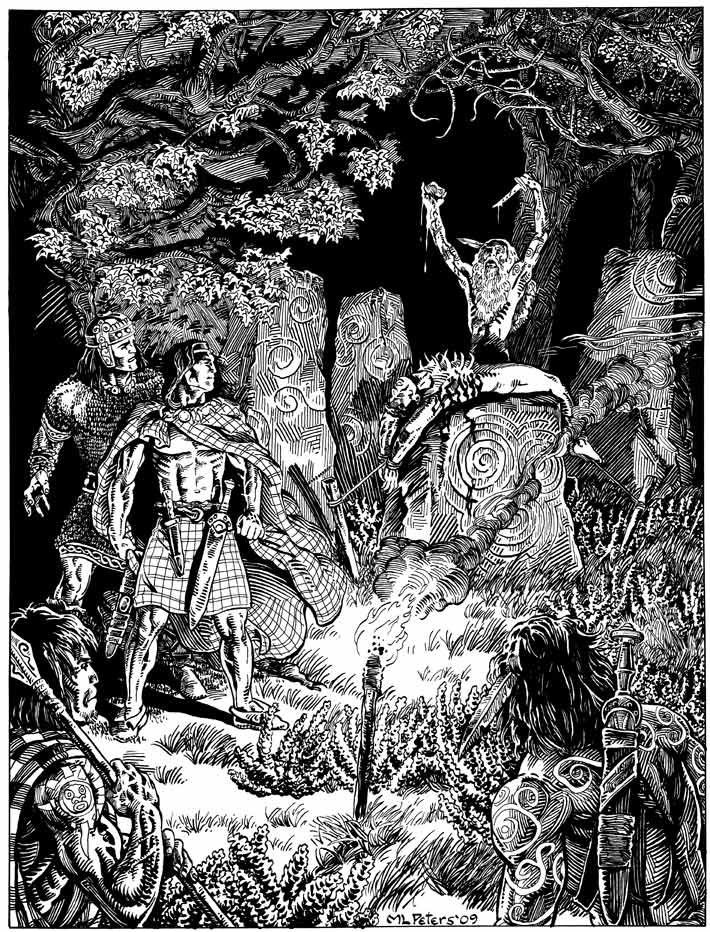

Here is a masterful example of a brief explanation of how the evil native wizard is calling up beasts of the dark wood to do his bidding. It has the flavor of folk lore, of native tales, and things forgotten by civilized men.

“Once all living things worshipped Jhebbal Sag. That was long ago, when beasts and men spoke one language. Men have forgotten him; even the beasts forget. Only a few remember. The men who remember Jhebbal Sag and the beasts who remember are brothers and speak the same tongue.”

It is a simple idea, to the point, yet has that air of occult antiquity that seems almost real. If there is not a folk tale like this, there should be.

Conan pauses to utter an opinion demeaning civilized man.

“Civilized men laugh,” said Conan. “But not one can tell me how Zogar Sag can call pythons and tigers and leopards out of the wilderness and make them do his bidding. They would say it is a lie, if they dared. That’s the way with civilized men. When they can’t explain something by their half-baked science, they refuse to believe it.”

The use of the phrase “half-baked science” — meant to chide the scientific skeptics in their overweening pride, — rings here like tin, since no barbarian dealing with bronze age civilizations would utter it. One of the highest civilizations of the ancient world, the Chinese, was ruled from the Forbidden City, of which no more extravagantly superstitious edifice of man has ever been built: even the number of rooms, their location, and furnishings, and decoration are all meant to deter bad luck and incur good, from the bat motif of certain ceilings, to the narrow shape of the beds.

The men at whom Conan scoffs, the materialists who follow Darwin, Freud, Marx, Nietzsche, and Skinner, would not be born for another age. Even the materialists of the ancient world, men like Lucretius, believed in gods and ghosts – but held that these creatures were made of atoms more subtle than human atoms.

Many an ancient sage or philosopher might scoff that magic was vain, unreliable, or wicked, but if there is even one who scoffed that the magic powers of priests and sibyls, nymphs and devils, one and all were shams perpetrated by fraud, I have yet to be made aware of it.

Conan, in a later scene, confronts and speaks with one of the apparitions stalking through the dark wood to kill him. It lures him close by mimicking the voice of a friend, glowing and glittering with eerie fire.

“The loon which is messenger to the Four Brothers of the Night flew swiftly and whispered your name in my ear. Your race is run. You are a dead man already. Your head will hang in the altar-hut of my brother. Your body will be eaten by the black-winged, sharp-beaked Children of Jhil.”

This has the tone and mood tribal gods, exactly suited to this setting.

Throughout the story, we are reminded that our barbarian hero is meant be the primeval exemplar of all that is raw and savage in the ancient world, as thus:

The barbarian’s eyes were smoldering with fires that never lit the eyes of men bred to the ideas of civilization. In that instant he was all wild, and had forgotten the man at his side. In his burning gaze Balthus glimpsed and vaguely recognized pristine images and half-embodied memories, shadows from Life’s dawn, forgotten and repudiated by sophisticated races—ancient, primeval fantasms unnamed and nameless.

One scene later, Conan complains that the government would not build forts in places and numbers sufficient to protect settlers from Picts, saying:

“Soft-bellied fools sitting on velvet cushions with naked girls offering them iced wine on their knees.—I know the breed. They can’t see any farther than their palace wall. Diplomacy—hell! They’d fight Picts with theories of territorial expansion.”

This is a jarring note.

The primal supermen of myth and legend, from Enkidu to Siegfried to Tarzan, if they pause to criticize the unpragmatism of an underfunded military policy of colonial expansionism, suddenly lose something of their stature, if not become become absurd, as if a caveman entered a faculty lounge and donned a bow tie to discuss marginal tax rates.

On the other hand, this is Conan late in his career, and he takes up the kingship of Aquilonia, and will have to set both tax rates and military policy in the course of his royal duties, so perhaps this is perfectly realistic. Even an archetype character must have some realistic aspects to his portrayal, lest he be a stereotype.

On the gripping hand, only highly sophisticated and overcivilized people reject civilization. Barbarians crave civilization, and are perfectly willing to forego the bow and arrow for the firearm — some even worship civilization and its goods, even to the point of creating a “Cargo Cult” and erecting mimic landing strips in honor of aircraft flying overhead.

I would be remiss if I did not mention one of Robert E. Howard’s most vivid, if very briefly mentioned, characters. Of course I mean the hard and loyal frontier dog, Slasher.

“That dog belonged to a settler who tried to build his cabin on the bank of the river a few miles south of the fort,” gruntcd Conan. “The Picts slipped over and killed him, of course, and burned his cabin. We found him dead among the embers, and the dog lying senseless among three Picts he’d killed. He was almost cut to pieces. We took him to the fort and dressed his wounds, but after he recovered he took to the woods and turned wild. —What now, Slasher, are you hunting the men who killed your master?”

Balthus raises a hand to pet the creature, who flinches, having forgotten kindness from the hand of man. The dog is tough and lean and scarred both in body and soul. Balthus sees that the frontier was no less hard for beasts than for men.

Not to worry. Slasher with red jaws kills more armed warriors in frantic, bloody skirmishes in the knighted woodlands than Balthus does over the next few pages.

Conan, at one point, tells of his great travels. It is worth quoting in full:

“I’ve roamed far; farther than any other man of my race ever wandered. I’ve seen all the great cities of the Hyborians, the Shemites, the Stygians, and the Hyrkanians. I’ve roamed in the unknown countries south of the black kingdoms of Kush, and east of the Sea of Vilayet. I’ve been a mercenary captain, a corsair, a kozak, a penniless vagabond, a general—hell, I’ve been everything except a king of a civilized country, and I may be that, before I die.” The fancy pleased him, and he grinned hardly. Then he shrugged his shoulders and stretched his mighty figure on the rocks. “This is as good a life as any. I don’t know how long I’ll stay on the frontier; a week, a month, a year. I have a roving foot. But it’s as well on the border as anywhere.”

Perfect.

And, as a nod to the fans, note the foreshadowing of his next career: the internal chronology hints that the events in Phoenix on the Sword are in his near future.

Here, again, is the summation of Conan as the archetype of noble savage:

The Cimmerian … was concerned only with the naked fundamentals of life. The warm intimacies of small, kindly things, the sentiments and delicious trivialities that make up so much of civilized men’s lives were meaningless to him. A wolf was no less a wolf because a whim of chance caused him to run with the watch-dogs. Bloodshed and violence and savagery were the natural elements of the life Conan knew; he could not, and would never, understand the little things that are so dear to civilized men and women.

A good a summary of the whole Nietzsche-era philosophy glamorizing everything cruel and crude, and scoffing at civilization as effete, which undergirds the whole appeal of the Conan stories.

If one cannot, even in the imagination, enter into the disgust which at one time or another, touches the wild heart of a raw and eager stripling, when he tires of the perfumed courtesies and legalities of ordered life, these tales will not touch you.

Dog and soldier die a hero’s death, saving fleeing women and children, but the government surrenders the disputed terrain back to the savages, and withdraws. The burned fort will not be rebuilt.

With these grim words, the story ends:

“Barbarism is the natural state of mankind … Civilization is unnatural. It is a whim of circumstance. And barbarism must always ultimately triumph.”