Conan: Hour of the Dragon

Hour of the Dragon was first serialized in Weird Tales magazine, appearing between December of 1935 to April of 1936. It was later published by Gnome Press in 1950 in hardback as Conan the Conqueror. The first Weird Tales episode came one month after Man-Eaters of Zamboula. It is the seventeenth published story in the Conan canon, and the last to see print in Robert E Howard’s lifetime. It is also the author’s only novel-length Conan tale.

Spoilers abound below.

If you have not read it, please avail yourself of that pleasure before reading this review. Like many classics pulps tales of yore, it is available to read without fee, and you may enjoy it.

In HOUR OF THE DRAGON, which is the last tale Howard told of Conan while alive, the brooding Cimmerian returns to his roots, and we see him in the same situation and same scenario as his first tale The Phoenix on the Sword : Conan is set on the throne he won in battle, and beset by corrupt courtiers and treacherous nobles, who, unable to face his sword or undermine his popularity, stoop to unmanly and unnatural sorcery to undo his rule.

We are reintroduced to his loyal friends, Count Trocero of Poitain and his general, Prospero. We meet his wife to be. Not without supernatural aid, Conan’s savage sword prevails. It is a fitting farewell.

Technically, Red Nails is the last tale Howard wrote, sold before his death and seeing print the month after. Two tales not published in his lifetime are The God In The Bowl and The Black Stranger. Posthumous collaborations and pastiches, some better and some worse, and retellings in comic, film, television, and even radio plays, continue to this day beyond my patience to count.

Nonetheless, by the internal chronology of the stories, we may consider this the final foray of Conan, because the theme of his departed life as an adventurer here comes to a finale, and the untold story of his life as king and father and founder of a dynasty is implied.

It is noteworthy that the whole span of the Conan canon, the whole of the tales published by Robert E Howard, from first to last, ran from December of 1932 to October of 1936, a mere four years, and comprised less than a score of stories.

I must confess this is not my favorite Conan tale.

Some authors are better suited to the tension and economy of the short story or novella, and the architectural foresight and craft needed to maintain raising and falling action in due proportion across the span of a whole book is not theirs.

Both H.P. Lovecraft, in his sole novel-length work DREAMQUEST OF UNKNOWN KADATH and Robert E. Howard in HOUR OF THE DRAGON, betray this limitation. Both novels consist of a series of episodes connected only by the main character, who himself displays no character growth nor change throughout.

In this case, the episodes are straightforward, eerie or action-packed by turns, but no characters are carried over from one to the next, and there are few dramatic plot twists here, as we have seen in some shorter tales, and no single theme, setting, nor central event.

There is however ferocious action from start to finish, fray and fracas by land and sea, epic clashes of chivalry and infantry by the thousands, fights in a haunted forests or ancient temples; and these various vivid scenes are visited by necromancers bestirring the undead to a hideous mockery of life, sinister priests and sneaking footpads, slave revolts and sudden death, oriental assassins with eerie powers; here is torture, revenge, betrayal and escape; not to mention slave girls yearning for true love or voluptuous vampire-queens yearning for living blood; while an unliving sorcerer-king of ancient Acheron slumbers in the sinister opium dreams of the fumes of the black lotus.

In this longer work, and Conan is King, so he has leisure to mention his political philosophy:

I but wish to hold what is mine. I have no desire to rule an empire welded together by blood and fire. It’s one thing to seize a throne with the aid of its subjects and rule them with their consent. It’s another to subjugate a foreign realm and rule it by fear…

Tyranny in the original sense of the word referred to any sovereign elevated to the throne by force of arms rather than claim of right. Conan is one such, as is any founder of a dynasty. His stated philosophy divides the popular and paternal form of such a tyranny from unpopular and alien, as must be the case when building empires.

Volumes could be written on the insight. Perhaps learning to bear the weight of a royal crown made Conan wise.

Conan also has time to take the measure of the age in which he lives, which cannot live up to this rule:

“Age follows age in the history of the world, and now we enter an age of horror and slavery, as it was long ago.”

Speaks Howard here of the Hyborian age or his own, on the eve of world war renewed?

The days of … free cities are past, the days of empires are upon us. Rulers are dreaming imperial dreams, and only in unity is there strength …

Again, speaks he of the Hyborian Age, or ours?

HOUR OF THE DRAGON opens with an evocative scene worthy of Howard, setting the mood and ensnaring the reader immediately via a few well-chosen words with intimations of the momentous and eldritch events to come.

Four conspirators, possessed of courage as profound as their lawless ambitions and capacity for evil, through darkest magic, seek to restore the mummy of the ancient wizard Xaltotun to life, using a mystic gem or talisman called the Heart of Ahriman, and, with his help, to overthrow the realm Conan rules as a just and well-loved king.

As is also typical of Howard, the political situation is complex rather than simple, as it would have been had Howard been writing historical fiction rather than prehistorical:

One of the conspirators is an evil priest turned necromancer who hopes to wake the dead; the second, a prince who schemes to slay his royal brother and usurp the neighboring kingdom of Nemedia; the third is an exiled kinsman to the king Conan overthrew, hence claimant to the throne of Aquilonia; and finally is the wealthy Nemedian baron funding and backing both their ambitions, who means to rule two kingdoms through them, and, eventually, all the civilized world.

Unfortunately, having created such a splendid and larger-than-life anti-hero in Conan, Howard often has difficulty making Conan’s opponents memorable. They cannot be pillars of virtue, for there is no such thing in the picaresque world of the Hyborian Age; and cannot be bolder, fiercer, stronger, more savage or more manly than Conan, for there is no such thing in any world.

The whole point and theme of the Conan stories is that something inexpressibly precious is siphoned out of the souls of men when civilization grows old: a rude courage, a savage sense of honor, an unselfconscious strength and simplicity which scoffs complexity, legalism, self-restraint, hence which scorns deception, occultism, conspiracy, and all craven sleights.

This means the civilized and mortal men conspiring against Conan rarely have any astounding virtue or grandiose villainy to them, save for sorcerers.

In this case, the four men are described as: large; small and dark; tall and yellow-haired; large; and their names are Orastes, Tarascus, Valerius, Amalric. I had to reread the passage where they are introduced nine times to remind myself of their names and roles. They are not memorable.

Likewise, Xaltotun himself cuts a somewhat forgettable figure, at least to look at, described merely as “a tall, lusty man, white of skin, and dark of hair and beard” but his dark eyes are “deep and strange and luminous.”

Hence our rogues gallery, at the beginning, consists of two princes, two sorcerers, and a rich baron. More rogues are encountered later, as the plot unfolds. Many more.

No doubt, like the child in THE PRINCESS BRIDE, you are wondering which of these five villains Conan kills. Like the grandfather, I needs must report that he kills none of them.

There is a comic book adaptation where Conan is on hand to slay two or three of them, but, alas, in the original text, it is not so. More on this later.

As hinted above, sorcerers in a sword-and-sorcery tale tend to be grandiose, and have more grandiloquent lines, than evil princes or bad barons. Orastes, the necromancer who revives Xaltotun, is given a paragraph to expound his dread and dreadful past:

“I AM no longer a priest of Mitra,” answered Orastes. “I was cast forth from my order because of my delving in black magic. But for Amalric there I might have been burned as a magician.

“But that left me free to pursue my studies. I journeyed in Zamora, in Vendhya, in Stygia, and among the haunted jungles of Khitai. I read the ironbound books of Skelos, and talked with unseen creatures in deep wells, and faceless shapes in black reeking jungles. I obtained a glimpse of your sarcophagus in the demon-haunted crypts below the black giant-walled temple of Set in the hinterlands of Stygia, and I learned of the arts that would bring back life to your shriveled corpse. From moldering manuscripts I learned of the Heart of Ahriman. Then for a year I sought its hiding-place, and at last I found it.”

And again, like the unwise wizard who wakens him, Xaltotun is grand in his great evil. His ambitions are befitting to the greatest wizard of three thousand years. When he gazes on a modern map, a momentary hatred is seen in his dark eyes: the merest hint of his true motives.

Unbeknownst to the other conspirators, who learn to their regret what they have conjured up, Xaltotun means to use his own necromancy not to resurrect another dead man or two, but to summon up his entire fallen empire from out of the misty abyss of time.

He means to change the shape of hills and rivers and coastlines back to what they were millennia ago, raise up the purple towers of the fallen city of Python, and bring whole multitudes out of their graves to resume their old places.

This ambitious is so awful, awesome, and so unholy, that one of the conspirators is driven mad merely to discover it, for he sees or senses the shadowy hills, dry rivers, empty palaces, silent multitudes of shades and whole spectral landscapes like ghosts poised to take the places of their living counterparts: and upon uttering a warning, he dies the death.

Please note that in the world of Conan, magic able to raise whole cities back from dead eons has previously been established, as seen in The Devil in Iron.

It is hinted, but not stated, that the priests of Asura who aid Conan against Xaltotun have the ability to penetrate illusions. Their highpriest states that Xaltotun never was other than the withered mummy as he was in his casket, not the robust dark-bearded man he seemed to be while walking the earth. If so, Xaltotun is a dead man is deceived by mesmeric illusion into thinking himself alive. But this is never stated outright to be the case.

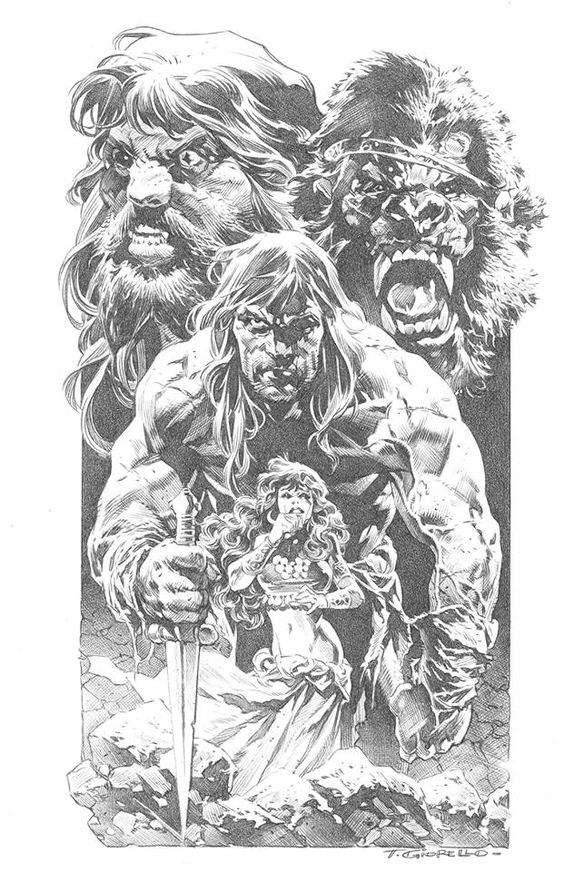

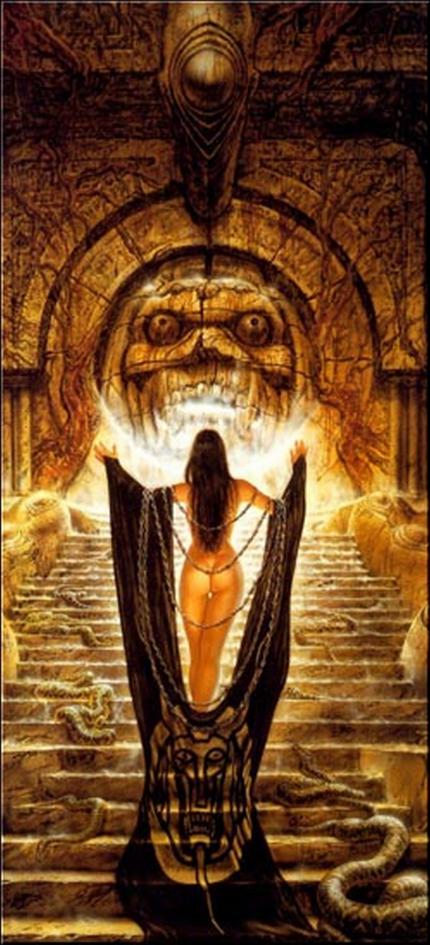

Note the Egyptian headgear and fleshless skull. Xaltotun in the text is nothing remotely like this.

Despite being a mummy, Xaltotun is not from pre-cataclysmic Egypt, called Stygia. He hails from the lands currently occupied by the new kingdoms — including Conan’s Aquilonia — hence has strongest motive to replace them with ghost lands he once knew. More to the point, Conan, as a barbarian, is from a similar northern stock as the barbaric hordes that sacked Acheron, and so the undead sorcerer-king has personal enmity against Conan, a grudge older than millennia.

The plot unfolds rapidly, indeed, at times too rapidly, as great events occur offstage only to be summarized in text or dialog. Xaltotun conjures plagues to slay kings and summons earthquakes to bury armies alive, and his dreadful night-sendings paralyze the mighty Conan, leaving him comatose.

Conan the king has no heirs, and no barons popular enough to unify the kingdom. Rather than anarchy, the people elevate Valerius the pretender to their throne, whereupon taxgatherers rob rich and poor alike, spies and informers spread division and distrust, malcontents are jailed and murdered, comely maidens are kidnapped off public streets, villages and castles plundered and burned, crops fail, cattle die, and all the disorders of an ill-governed kingdom are combined with all the humiliation and despotism of foreign conquest. And all think Conan dead.

However, something of the grim realism of a historical novel is present in this prehistoric fantasy, for as in our age, in the Hyborian Age conspirators inevitably conspire against each other.

For Xaltotun, instead of slaying Conan as agreed, spirits him away on his spectral chariot to his haunted dungeons of horror, for he hopes to use Conan against his erstwhile allies.

Meanwhile the wicked but capable king Tarascus, for the selfsame reason, steals the Heart of Ahriman from Xaltotun while the wizard is in the trancelike death-sleep of the fumes of the black lotus, sending his henchman to cast the magical talisman into the sea.

Meanwhile the wicked and incompetent king Valerius decides to betray the both of them by deliberately running Aquilonia into such ruin as will topple both kingdoms: and to see to Conan’s death, he sends out four mystic assassins of far Khitan, in later ages called Cathay.

But these oriental minions, unbeknownst to their master, have ulterior motives, for seek not merely to cut out the heart of Conan, but to rob the Heart of Ahriman from the minion of the other conspirator Tarascus.

These unnamed mystic assassins can trace their prey across land and sea by unknown means, can read hearts, and the staffs they wield, cut from the living tree of death, become poisonous snakes in their hands as they strike.

But all these minions and assassins are opposed by malevolent archpriests of Set the serpent-god from Stygia, from whose demon-guarded vaults of eternal night the talisman was long ago stolen by the henchman of Orastes. Two of these archpriests, naturally, are riven with rivalry, hence conspiring against each other.

Conan is secretly imprisoned by Xaltotun when Tarascus secretly sends agents to slay him by stealth while he is in chains. And even a girl of his seraglio is conspiring against Tarascus, and all these conspirators, as it turns out, she alone is ultimately successful.

Aided by the cunning of a nubile slavegirl named Zenobia, who fell in love with him and worships him from afar, Conan escapes his cell, and, after a naked knife fight in the dark with one of the silent, monstrous, man-eating great apes from beyond the eastern sea, wins free of the nightmare dungeon.

The sultry brunette is not only supple, dark-eyed and half-naked, she is strong-hearted and cool-headed enough to beguile and benumb guards with drugged wine, to filch keys, and to steal a fine steed fully equipped for Conan’s getaway, as well as a stout blade for his hand. As with most Conan women, she possesses the wanton and immodest beauty of pagan eras, but an abundant measure of wit and nerve. Zenobia is also a good judges of horses, and weapons, and men.

When she candidly confesses her helpless love for him, even Conan is momentary abashed, wild and passionate and untamed though he is. The text confirms that “any but the most brutish of men must be touched with a certain awe or wonder at the baring of a woman’s naked soul.”

This, if memory serves, is the only hint that Conan is ever awed by the affection of the several amorous beauties, pirate queens or paramours, countesses or courtesans, with whom he dallies. Passion he has known before, desire and grief; but this hints at more than even he felt toward Belit or Valeria — but this is a boy’s adventure story, not a girl’s romance, so we glimpse no more than this hint.

But he promises to come for her some day.

Conan flees across the border to Aquilonia, slaying pursuers and patrols, and donning captured harness and gear to travel in disguise, a fugitive in his own kingdom, but tracked from the air by magic. He saves a mountain witch named Zelata and her great gray wolf, and she, in turn, uses her mysterious powers to guide him and misguide his pursuit.

He meets with loyalists, but they report it impossible to revive a revolt among the people, for fear of the sorcery, which Conan, merely mortal, cannot fight alone. He would be wiser to go into exile, but instead he stays the save a maiden in distress.

Conan alone by hidden passage enters the dread Iron Tower at midnight rashly to rescue from execution a lovely countess named Albiona, who refused the usurper’s lawless lusts.

Conan in the ill-lit death chamber, disguised as an executioner, slaughters headsmen and henchmen alike to free her, but the fleeing pair is cornered by pursuers, only to be whisked to safety by the priests of Asura.

From these eerie priests of darkness, Conan discovers the identity of Xaltotun, and learns that the Heart of Ahriman, his foe’s sole weakness, is being carried south.

The talisman has the power to summon up the dead, and so every Eastern sorcerer, Southern mystic and Western alchemist seeks to have it; the original ruffian porting it was slain, the jewel is now in the locked puzzle-box of a Kothic smuggler, who treads a dangerous trail through haunted western forests to reach Kordava, the city of thieves on the coast.

The priests of Asura risk death to smuggle Conan to friendly a province to the south disguised as a mortician on a funeral barge, with Albiona hidden in the casket.

The reason for their solicitude is simple gratitude: during his reign, while evil men and evil rumors harassed them, Conan granted the priests of Asura to leave to practice their secretive rites unmolested in his kingdom.

The text explains:

But Conan’s was the broad tolerance of the barbarian, and he had refused to persecute the followers of Asura or to allow the people to do so on no better evidence than was presented against them, rumors and accusations that could not be proven. “If they are black magicians,” he had said, “how will they suffer you to harry them? If they are not, there is no evil in them. Crom’s devils! Let men worship what gods they will.”

Spoken with the nearsighted folly of nihilist agnosticism. Crom’s devils are surely pleased if men worship what gods they will.

The idea that a barbarian insists on due process of law, and broadly tolerates the worship of outlandish deities from enemy lands is the exact opposite of what barbarism means and is. Civilized men know chivalry, this is, the concept that even foes are as brothers, with souls as rich as one’s own, or that even criminals have God-given rights. The thing that makes barbarians barbarous is that lack of fellow-feeling toward foes, respect for law, the luxury of mercy. They grovel in defeat and vaunt in victory, the mere opposite of stoicism, sportsmanship, broadmindedness.

For the record, this is the sole passage I remember from my far vanished youth when I read this tale long ago. All else I utterly forgot. I recalled this passage because it did not fit into the story background. Even as a beardless boy, I knew it was out of place.

Howard, as an American, might praise freedom of faith. No man of Howard’s world would.

We see why a few scenes later, when Conan, treading the streets of Stygia by night, is chilled by the thought of the dark gods ruling here.

Set the Old Serpent, men said, banished long ago from the Hyborian races, yet lurked in the shadows of the cryptic temples, and awful and mysterious were the deeds done in the nighted shrines.

So … What about the easy tolerance of the barbarian? If man be let to worship what gods they will, why not worship Set, and release man-eating snakes into city streets at night to strangle wayfarers and vagrants?

And Conan is less likely than any modern man to tolerate cultists worshipping unknown possibly Lovecraftian gods, because he has fought them face to face many a time. Conan dwells in a world where worshippers of unknown gods can unleash real demons or wake real undead sorcerer-kings to enslave and slaughter whole cities or kingdoms.

Bad gods in Conan’s world outnumber good gods by a considerable number.

No civilized man would tolerate witches worshipping pagan gods for an instant if pagan gods could do what they do in stories, ravish women, metamorphosize men into birds or trees, &c, any more than he would tolerate quislings collaborating with invading Germans, or tolerate Russian spies; nor would any savage, noble or not.

Leaving the unearthly priests of Asura behind, Conan meets with loyal barons in Poitain, a lush land akin to Gascony. Conan notes the gentle land, since it invites generations of invasions from jealous neighbors to their north and west, has bred the native knights to hardihood.

It is not only the hard lands that breed hard men

This is an interesting reverse from the otherwise ubiquitous theme of the superiority of the valor of the barbarian.

Conan is waylaid by knights who recognize him.

“Saints of heaven!” he gasped. “It is the king—alive!”

An interesting choice of cuss word. Not the normal vow by Mitra.

It strikes an alien note. For the same reason noblemen are ignoble in a picaresque novel, rich men venal, women immodest, the gods are free to be as evil as can be, but the good gods never so very good, or else our noble anti-hero and loveable rogue might be seen as not so loveable after all. Antiheroes next to heroes are villains. Glamor lures only when truth is absent.

Conan, after consulting with loyal nobles, decides to pursue the talisman alone. His path will take him from the hands of unscrupulous mercenaries to the torture chamber of a robber baron; to the moonless crossroads of a cursed forest where dog-faced ghouls waylay travelers and feast on their flesh; thence to the smuggler’s haven where pirate comrades from older days recall him.

Here is a snippet of the dialog ere he sets out:

“So I’m riding to Kordava, alone.”

“But that is dangerous,” protested Trocero.

“Life is dangerous,” rumbled the king.

The author discovers perfectly likely reasons to have his protagonist king, despite that no king would, depart alone.

In the first place, he is deposed. Second, the mission calls for speed and silence. Third, he goes to land where he has old friends who would not trust a king arriving with a squad of knights. Fourth, he knows not whom to trust. Finally, he is Conan of Cimmeria! What agent or minion could he in his place send more badass than he?

But the fifth reason Conan does not admit. When he dressed up in the gear of a roving swordsman, a change overcomes him:

And more than looking the part, he felt the part; the awakening of old memories, the resurge of the wild, mad, glorious days of old before his feet were set on the imperial path when he was a wandering mercenary, roistering, brawling, guzzling, adventuring, with no thought for the morrow, and no desire save sparkling ale, red lips, and a keen sword to swing on all the battlefields of the world.

A good flourish of character development.

After several adventures, Conan intrudes on old comrade of his days when Conan the buccaneer called Amra. Publio is his name, and he has since found a life as a respectable merchant.

“I have not stolen, cheated, lied and fought my way up from the gutter to be undone now by a ghost out of my past,” muttered Publio, and the sinister darkness of his countenance at that moment would have surprised the wealthy nobles and ladies, who bought their silks and pearls from his many stalls.

Note that no wealthy merchant in a Conan story ever earns or merits his wealth. This is a commonplace in such stories, to free our thievish antihero to despoil and humiliate the rich. No tale of loveable rogues ever shows the rogue robbing the poor, nor even from self-made men who enjoy their earnings honestly.

Publio, setting the platter on the table with a sigh of relief, for it was heavily laden; he knew his guest of old.

Another apt little tidbit. Of course Conan has a lusty appetite, even late in middle age.

Conan is soon beset by footpads sent by Publio, who thought it better to betray his old pirate chief. After furious fight, Conan is left for dead on the moonlit shore. The unprofessional cutthroats do not bother to cut his throat, for even then a press gang wanders nigh, looking for sailors to shanghai.

Conan wakes to find himself enslaved aboard a galley from Argos. Here, among the slaves, Conan sees stalwart figures he recognizes.

The life of a slave aboard an Argossean galley was a hell unfathomable…. Conan recognized them by their straighter features and by their rangier, cleaner-limbed build. And he saw among them men who had followed him of old.

Yes, these are the pirates of the Black Coast who followed his bloodstained flag in days of old. Awesome…

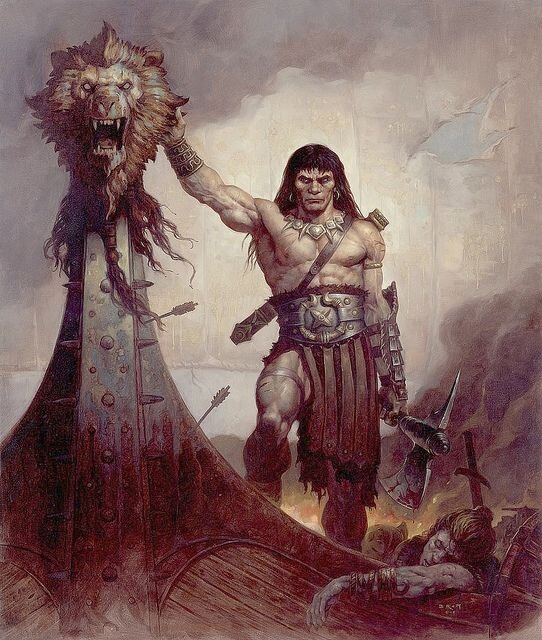

Conan bounded out on the bridge and stood poised above the upturned black faces, ax lifted, black mane blown in the wind. “Who am I?” he yelled. “Look, you dogs! Look, Ajonga, Yasunga, Laranga! Who am I?”

And from the waist rose a shout that swelled to a mighty roar: “Amra! It is Amra! The Lion has returned!”

The sailors who caught and understood the burden of that awesome shout paled and shrank back, staring in sudden fear at the wild figure on the bridge…

Twice awesome…

Conan, his mighty chest heaving and glistening with sweat, the red ax gripped in his blood-smeared hand, glared about him as the first of men might have glared in some primordial dawn, and shook back his black mane. In that moment he was not king of Aquilonia; he was again lord of the black corsairs, who had hacked his way to lordship through flame and blood.

Thrice awesome, and moreso. This is why we read Conan yarns.

After more fights, escapes, giant snakes, disguises, hidden tombs and haunted pyramids in antique lands, dark rites and eldritch horrors, and a scene of villains slaying villains in their lust for the treasured talisman everyone seeks, Conan finally recovers the Heart of Ahriman and returns north in time for a three-chapter set piece of medieval battle.

Conan first sends a threatening note to Xaltotun, telling of his return. The conspirators puzzle over the document, thinking Conan dead. One says:

“It is genuine. I have compared it with the signature on the royal documents in the libraries of the court. None could imitate that bold scrawl.”

Of course Conan has an inimitable bold scrawl. Of course.

It is bold because he is a barbarian. It is a scrawl because his origins are unlettered. It is inimitable because he is Conan, for Crom’s sake! What else would we expect?! He is not some schlub whose letters anyone can mimic!

For the final battle, Xaltotun calls on his allies, the evil princes who now mistrust him, to rally troops. When asked why he does not simply blast Conan from afar with plague or storm, the sorcerer admits:

Magic depended, to a certain extent after all, on sword strokes and lance thrusts…

This adumbrates interesting limitations on the power of magic. Later we are told the more sinister reason: the blood shed on the battlefield stirs up dark spirits, and permits darker magic to prevail.

Here we see one of the basic problems facing any author who ventures having a magical creature or character in his tale. Namely, once you introduce magic as a force in your world you have to establish why it does not solve all the problems.

Why, for example, can the evil wizard not discover the hero’s location by clairvoyance, and bedevil or slay him via voodoo curse from a many leagues away; or, worse, why had not the warlock foreseen all by astrology or crystal ball, and sent his demon-snakes to strangle hero in his crib as child, many years before?

In all such tales, magic can establish the obstacles, and even set the rules by which sleeping princesses, frog princes, or cursed kingdoms can be saved or damned, and magic can be used to overcome magic, but ought not solve the final obstacle, not if your hero is a hero.

Trickster figures, perhaps, or loveable rogues can triumph over tyrants by means of illusions and sleight of hand, but there is something occult and unsavory about magic in every well-written tale, and even the marvels of fairy godmothers and the miracles of saints should be seem as unearthly, numinous, and fearsome to the god-fearing.

In well-written stories, magicians depart from the human lands for their shadow realms, and if they return to the world of daylight, they come back strangely changed. Their ways are not our ways.

However, this creates a vexatious problem every author of such tales must negotiate, namely, how to have sword overcome wizardry, or swordsman armed with steel overcome sorcerer armed with supernal powers?

One way is to establish the terms of the curse needed to compass the malefactor’s downfall, discovering his name, flourishing a crucifix, or finding where his disembodies heart is hid, or throwing his ring into the mountain of fire where it was forged, or some such. Another way is to have Aslan the Lion claw the witch to death, or seven dwarves chase her off a cliff during a lightning storm, or otherwise using otherworldly help to defeat the otherworld. A more direct approach, as Wormtongue discovered, is merely to stab the wizard with an iron blade. And so on.

Here, unfortunately, Howard elects the second way, and has a duel of magic between Xaltotun and a minor character with no personal stake in the matter, the chief priest of Asura to whom Conan give the Heart of Ahriman. And it is somewhat of an indirect duel, involving storms that fail to flood rivers, and fogbanks that successfully hide an ambush. I call it unfortunate, because the whole last act of Howard’s sole novel-length attempt fails to drain each last dram of drama from the situation established, and, indeed, at times, becomes perfunctory.

To his credit, Robert E Howard credits the victory of the outnumbered heroes to their morale and their training. He emphasizes how mercenaries fighting for pay are less in spirit than men fighting for hearth and home, for their liberties and their lady wives.

The imagery, as befits popular prose from pulps of days gone by, is gorgeous.

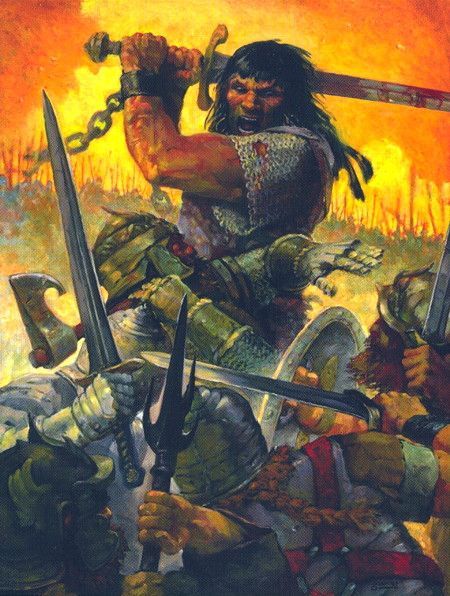

Their plumes and pennons streaming out behind them, their lances lowered, they swept over the wavering lines of pikemen and roared down the slopes like a wave.

The whole passage does not sound like it comes from the bronze age. The knights with their lances and pennants and the footman armed with pike and crossbow come from a medieval romance.

The Hyborian Age is not the Bronze Age, but a deliberate collage and pastiche of all ages a historical novelist might want to visit, freed from the factual fetters of real history.

If you want to pen a story about Chinese Taoist warlocks battling ancient Hermetic priests of Egypt over a magic Persian jewel that holds the soul of a Roman warlock brought back to a hideous mockery of life into Charlemagne’s kingdom by necromancy, while Frankish knights and Welsh longbowman rebel against that warlock, led by their barbaric Celtic warlord who was once a Caribbean pirate-king preying on the Gold Coast of Africa, with Lovecraftian demon-gods, man-apes, mummies, and man-eating Neanderthals lurking in the background, no real period in real history will sate all your needs.

Hence the simple brilliance of Howard’s discovery of an age after the sinking of Atlantis but before the rise of the Sons of Aryas, an age undreamed of.

In the final battle, Conan himself is mentioned only in passing and not by name:

They held their formation unshaken; over their gleaming ranks flowed the great lion banner, and at the tip of the wedge a giant figure in black armor roared and smote like a hurricane, with a dripping ax that split steel and bone alike.

That one reference to a giant figure is the whole of Conan’s role on the main battle we are told. We meet nothing from Conan’s viewpoint, see no debates over tactics with captains, hear no rousing speeches as one might hear on Saint Crispin’s Day, not even so much as a growling curse calling them dogs and telling them to set on.

Nor does Conan kill the evil baron, Amalric of Tor:

The final break did not come until the fall of Amalric. The baron, striving in vain to rally his men, rode straight at the clump of knights that followed the giant in black armor whose surcoat bore the royal lion, and over whose head floated the golden lion banner with the scarlet leopard of Poitain beside it. A tall warrior in gleaming armor couched his lance and charged to meet the lord of Tor. They met like a thunderclap. The Nemedian’s lance, striking his foe’s helmet, snapped bolts and rivets and tore off the casque, revealing the features of Pallantides. But the Aquilonian’s lance-head crashed through shield and breast-plate to transfix the baron’s heart.

Pallantides is Conan’s commander and aide de camp, who survived the fall of the kingdom in Chapter Two, and fled to Ophir. I confess I had forgotten this man’s name and his role, so, to me, his triumph over Baron Amalric lacked drama. Readers with sharper memories than mine will recall Pallantides as captain of the king’s elite bodyguard, the Black Dragons, in The Phoenix on the Sword.

Nor does Conan kill the evil pretender Valerius who took his throne. Instead, a skulking whip-scarred traitor named Tiberias leads Valerius and his knights into a mountain pass he promises leads into the unprotected flank of Conan’s army. But the traitor betrays his treason, and lures the fog-blinded knights into a blind canyon surrounded by all the beggars, escaped slaves, and broken men the misrule of Valerius plundered, maimed, dispossessed, despoiled. This is revenge.

Tiberias announces this motive in his dying speech, but nothing was shown onstage beforehand, nor was the character previously named nor seen. Conan is not present, nor even aware of these events. For that matter, the death of Valerius is not described.

The drums had begun again, encircling the gorge with guttural thunder; boulders came crashing down; above the screams of dying men shrilled the arrows in blinding clouds from the cliffs.

Nor does Conan kill the unconquerable archvillain Xaltotun. He is not even present. The witch Zelata is present but does nothing. Her great gray wolf is present but does nothing.

The wizard of Acheron went down as though struck by a thunderbolt, and before he touched the ground he was fearfully altered. Beside the altar-stone lay no fresh-slain corpse, but a shriveled mummy, a brown, dry, unrecognizable carcass sprawling among moldering swathings.

The curse that smites the wizard comes from a dark priest named Hadrathus, one of the priests of Asura aforementioned, after a windy exchange of vaunts and curses. As aforesaid, sorcerers get all the most grandiose lines.

Earlier, I said Xaltotun was a forgettable figure. His final fare-thee-well, however, is memorable:

from among the trees appeared a strange apparition—Xaltotun’s chariot drawn by the weird horses. Silently they advanced to the altar and halted, with the chariot wheel almost touching the brown withered thing on the grass. Hadrathus lifted the body of the wizard and placed it in the chariot. And without hesitation the uncanny steeds turned and moved off southward, down the hill. And Hadrathus and Zelata and the gray wolf watched them go down the long road to Acheron which is beyond the ken of men.

Perhaps the absence of Conan in all these scenes is a feint, meant to whet our impatience to sharpest hunger. Conan does indeed fight the enemy king of Nemedia, but downs him in personal combat after his army is routed. It is a fight scene of which none shorter can be penned. I repeat the whole of it below, in its entirety:

The two kings met man to man.

Even as they rode at each other, the horse of Tarascus sobbed and sank under him. Conan leaped from his own steed and ran at him, as the king of Nemedia disengaged himself and rose. Steel flashed blindingly in the sun, clashed loudly, and blue sparks flew; then a clang of armor as Tarascus measured his full length on the earth beneath a thunderous stroke of Conan’s broadsword.

The Cimmerian placed a mail-shod foot on his enemy’s breast, and lifted his sword. His helmet was gone; he shook back his black mane and his blue eyes blazed with their old fire.

“Do you yield?”

The paragraph where Conan lists the surrender terms is longer than the description of his fight. Surprisingly, or perhaps not surprisingly, the barbarian demands perfectly reasonable and just compensations, withdrawals, the surrender of garrisons, the manumission of slaves, payment for property damage, the exchange of hostages, and so on, as just and temperate as any civilized king would do.

The moment of old fire blazing in Conan’s blue eyes is the farewell to those fires. He is a prudent leader, a savage no more.

The vanquished king agrees to terms, but then asks what shall be his personal ransom? The final demand, and the price of his life and liberty, is not revealed until the final words of the story.

It must be said that this is also the final word of Conan’s chronology: no report of his family life nor final years reaches us from the time-drowned deeps of the Hyborian Age, when cataclysms reshaped the old continents into their new forms.

Sprague de Camp or Lin Carter or the dozen other post-Howardian Conan collaborators no doubt have penned tales of the children and grandchildren of the King of Aquilonia, but, if so, this reader has not read them. This is the end.

Conan is still uncivilized hence uncorrupt and unworldly enough not to ask a king’s ransom to ransom a king. He seeks more than gold.

“There is a girl in your seraglio named Zenobia.” … The king smiled as at an exceedingly pleasant memory. “She shall be your ransom, and naught else. I will come to Belverus for her as I promised. She was a slave in Nemedia, but I will make her queen of Aquilonia!”

Thus, the dynasty is established, and the legacy and legend of Conan is preserved.