Conan: God in the Bowl

God in the Bowl did not see publication until appearing in the pages of Space Science Fiction, September 1952, after it had been partly rewritten, perhaps to its detriment, by L. Sprague de Camp. The previous story in the Conan Canon, Red Nails, appeared in the September 1936 issue of Weird Tales: a gap of sixteen years.

God in the Bowl was among Robert E Howard’s unpublished manuscripts found after his passing away. It had been submitted, along with The Frost Giant’s Daughter and Phoenix on the Sword to Farnsworth Wright, editor of Weird Tales in 1932.

Farnsworth Wright wisely kept only Phoenix on the Sword and returned the other two. The reason for this is harsh and obvious: these two tales are inferior.

This story does not stand on its own, but it does contain, in brief, the central element of Conan’s theme, namely, a condemnation of the corruption of civilized men.

Let me discuss the story telling, first, which is poor, and next the theme, which is stark and clear, perhaps too clear.

But first a word of praise. Even in the poorest of his stories, Robert E Howard is still the master of lean, crisp, vivid prose, establishing scene and mood economically and clearly:

Arus the watchman grasped his crossbow with shaky hands, and he felt beads of clammy perspiration on his skin as he stared at the unlovely corpse sprawling on the polished floor before him. It is not pleasant to come upon Death in a lonely place at midnight.

By the internal chronology of the stories, this takes place when the brawny youth was first wandering among civilization, living hand-to-mouth as a thief and footpad. It is near in time to Tower of the Elephant, most likely, since this Conan is rougher and more naïve and more easily surprised, these events are the earlier. If so, this is Conan’s first brush with civilization.

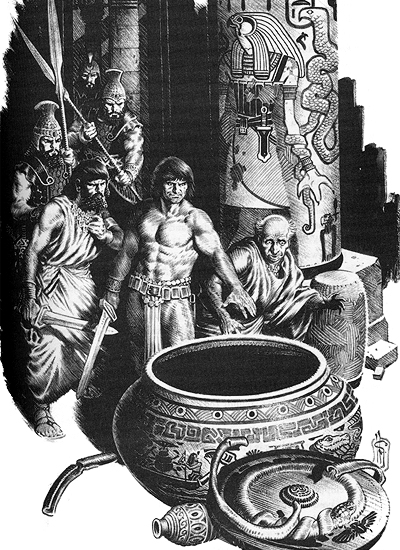

For some reason, one potentate among the men of the primordial world of prehistory keeps a museum with a night-watchman, where he gathers rare and expensive artifacts from distant lands. The night-watchman in short order stumbles across the potentate, who had been murdered, and then Conan.

So in the opening paragraphs, this reader, at least, suffers a twinge of disbelief.

To have a scene set in a museum in the remote past is as unlikely as having it set in a newspaper office or an airport. Temples to the muses existed, and surely wealthy collectors of rarities existed, but not museums. Rich men stored their treasures in their own houses, and did not display them to the public.

I would point out that curiosity about other cultures and ages was unknown in the ancient world. Egyptian hieroglyphs, for example, surely excited much attention in the era of Napoleon, because the language had been lost. Not a single mention in any surviving record is made, however, of any Roman scholar living in Egypt writing down how to read and write the local language, which at that time, was not lost. No Roman would have had to cross any international boundaries to go dig up the ruins of Troy. And yet this kind of curiosity had to wait for a Christian Age, and scholars from the later nations of Europe.

Setting the tale in a museum does not ruin the story, but it is a minus mark against it. It makes it a little harder to believe the story.

A mummy-haunted pyramid or ghoul-visited graveyard crumbling in the moonlight might be a less realistic scene for a spooky tale, because mummies and ghouls are not real. But either would fit in with the mood and atmosphere, not break it.

Story-telling is not governed by the rule of the believable. All fiction readers know fiction is fictional. Story-telling is governed by the rule of suspension of disbelief. As long as the story-teller keeps the integrity of the tale intact, and has men react as men would or should, no matter how unrealistic the setting or events, the reader will play along, and accept the unreal element for the sake of the tale.

So it was with me, with this, even though this is a small nit to pick. It did not come across that one eccentric rich man of the prehistorical Hyborian Age collected and kept rarities in a special building outside his house.

It came across that this was a draft of some whodunnit about a museum murder Howard had laying around, hastily rewritten to place it in the Hyborian Age, and with Conan thrust into the middle of it, given nothing to do, except that he, rather than the police detective, kills the murderer in the final paragraph.

Conan is here dressed as all stereotypes of this character would have him: wearing no more than a loincloth and sword. Canon, instead of attempting escape, stands by while the police arrive, led by the “chief of the Inquisitorial Council of the city of Numalia” or, in other words, the head detective.

Again, while there were indeed night watchmen in times of yore, the police detective hales from a later era, and carries with him a different atmosphere and mood, something belonging, at the earliest, to Scotland Yard. Call it a second mark against it.

By convenient coincidence, three other witnesses are found outside and dragged in to be questioned: a chauffer, an accountant, and a perfumed young dandy in expensive clothing who happens to be the nephew of the governor.

To keep up the appearance of being set in the Bronze Age, the chauffer is called a chariot driver, and the accountant is called a chief clerk.

Unfortunately, unlike every other location ever encountered in a Conan story, the city of Numalia and its inhabitants have no personality, nothing that lodges in the memory, except that the police inspector shows unusual restraint, and the police sergeant is unusually brutal.

All have vaguely Greco-Roman names, but nothing about the architecture, dress, weapons, artifacts or culture particular to Rome or Greece comes on stage. If these men had been Spartan, and spoken laconically, or Athenian, and spoken philosophically, or Roman, and committed suicide, that, at least, would have been something.

The lack of memorable background or local color may not be a minus, but it is certainly not a plus.

The bulk of the story consists of dialog and more dialog while the detective discovers the exact sequences of events, and his sergeant beats the truth out of the cowering clerk.

Seeing the brutality, Conan reacts “with a sneer of cruel contempt for the moaning clerk.”

Got that? He is not disgusted by beating, but at the inability of the clerk to take it. So much for the nobility of our noble savage. The hero of the tale is a villain. A third minus.

It seems the dead potentate meant to break open and loot a bowl-shaped sarcophagus he had been entrusted to ship from a Stygian wizard, servant of the snake-god Set, to the wizard’s arch-rival, a priest of Ibis. Fans of Conan will rejoice to hear the name of the wizard: it is Thoth-Amon. This figure was part of the Conan lore from the onset.

Conan himself entered the scene purely by coincidence. The author should have taken the time to make Conan’s crime and the crime he stumbles across have some sort of reason for happening on the same night. It would have only taken a line or two. The author did not. A fourth minus.

Conan seems to be there for no reason, an intruder into the story of Demetrio, Inquisitor of Numalia, solving an unlikely murder case.

Conan, when questioned, freely admits he was hired to break in and steal something. He will not say who or what.

When Conan refuses to answer questions, and the hard-boiled cop barks at him: “Oh, an insolent fellow! An independent cur! One of those citizens with rights, eh? I’ll soon knock it out of him! Here, you! Come clean!”

No one in the ancient world spoke of citizens with rights. There were no police forces properly so called until the early nineteenth century. Officers of the king or emperor were never hindered by laws protecting citizens from brutality or police overreach: these concepts are unknowable to the pagan mind. This is merely a line Howard forgot to redact from his original whodunnit manuscript — unless it was awkwardly inserted by de Camp, for it does not really sound Howardian to my ear.

Conan draws his sword, and the police make no move to arrest him. Neither does he attempt escape. Instead the police and felon glower at or ignore one another, while the police inspector finishes questioning witnesses.

Then, when the clerk finds the mysterious sarcophagus, and finds it empty (for the dead potentate had pried it open) he calls the police into the inner chamber.

The text at this point reads:

‘All followed, including Conan, who was apparently heedless of the wary eye the guardsmen kept on him, and seemed merely curious.’

I laughed aloud at that line. Imagine the police in any police drama allowing an armed and dangerous murder-suspect and confessed burglar nonchalantly follow the chief inspector into the crime scene, in a museum surrounded by priceless loot.

Neither the police nor the barbarian have any reason, other than the stiff clockwork demands of the plot, to keep Conan armed and at large and in the scene, once he has confessed to breaking and entering.

Even had the writer insisted on having Conan armed later in the story, since the opening paragraphs establish that several weapons of curious make are hanging on the walls close at hand, Conan could have easily rearmed himself for the final slaughter scene had it been needed by snatching one off a peg or something

There is a hint that the police are too intimidated to attempt to arrest him, but since they outnumber him, and are equipped with pole-arms and crossbows, the reluctance is incomprehensible. At least Demetrio could have sent a runner to the garrison for more men, surrounded the house, and starved Conan out.

But even that makes no sense. If Conan were so fierce a foe that he could dash them aside easily (as it later turns out to be the case), why does he linger?

In fairness, he perhaps is so barbaric at this point that he does not realize the cops intend to arrest him, or does not know what that means, and so he does not run because he sees no threat.

After all, he did not stop the night-watchman who discovered him from ringing the bell to summon the police, because he assumed the man was a thief like himself. This may be a sixth minus, or may not. If this were done to emphasize the innocence of the innocent savage, so be it, but I would have liked that point to be made a little more clearly.

But in any case, the savage does not fight nor run even after the police tell him that he will either be enslaved in the mines or burned at the stake. It made a story a little harder to believe for me, because I kept wondering what Conan was doing there, why he was neither fought nor fled, why he was being kept in at the crime scene at all.

It is a fifth minus mark. It was not enough to halt the story for me, but it was one more tap on the brake.

The third witness, who is also there due to unlikely coincidence, is the foppish and decadent young aristocrat who hired Conan to break in. The fop asked the barbarian to recover a rare gem-studded goblet from a hiding place only known to a few rich friends of the dead man.

The police inspector knows the fop is guilty, craving cash to pay off gambling debts, but says he can cover for the fop, hide the crime, if the fop will only admit he hired Conan for the burglary. This will save Conan from being burned alive, if not guilty of a capital crime.

The fop, whose name is Aztrias, merely yawns and shrugs his shoulders.

A gross fight scene immediately ensues.

“Conan struck with no more warning than a striking cobra; his sword flashed in the candlelight. Aztrias shrieked and his head flew from his shoulders in a shower of blood, the features frozen in a white mask of horror.”

So, a sneak attack against an unarmed foe.

Conan is not honorable here, which makes a mockery of the attempt to glorify his savagery. Here, for once, Howard fails in his attempt to make the noble savage seem noble. We see what he really is: both brutal and cowardly. (The cowardice is on the next page, when he runs blindly from a dead man-headed snake-monster he kills, terrified at its unearthly nature.)

“Cat-like, Conan wheeled and thrust murderously for Demetrio’s groin. The Inquisitor’s instinctive recoil barely deflected the point which sank into his thigh, glanced from the bone and ploughed out through the outer side of the leg. Demetrio went to his knee with a groan, unnerved and nauseated with agony.”

Even for Conan, this is nasty. A low blow.

Conan in short order plucks out a third man’s eye, leaving him screaming and clutching the gory socket, then tramples the face of a fallen fourth man, breaking jawbone and scattering bloody teeth.

The guy with the gouged-out eye admittedly had it coming, since he boasted of doing the same thing to a girl on the witness stand to wring a confession from her.

These three rapid paragraphs of graphic gore may prove too much for the unhardened reader, and may have been one reason Farnsworth Wright did not buy it.

There are several more minus marked earned in the brief scene, not the least of which is the minus earned for what it lacks: no strategy, no tactics, no thought, no sense of battle or valor.

The police simply form no threat worth fighting, and none of them, not one, lands a blow on the big barbarian, despite being superior in number and toting weapons with longer reach. All they would have had to have done is pin him with pole-arms into a corner while others pole-axed him at a safe distance. Or, better yet, shoot him with crossbows.

Nothing in any later Conan stories is like this: it sounds like something from a police blotter, very graphic without being realistic. Brutal, to be sure, but not worth reading.

Then, in a scene heavy-handed and unconvincing enough to dispel any remaining suspension of disbelief, a screaming man enters the chamber, babbling about a long necked god, and dies of fright.

The men in the middle of melee, fighting for their very lives, all halt and turn, fall silent, and gawp at this interruption, even those still clutching gushing eyesocket, leg-wound, or jaw-hole.

They all flee pell mell, trampling one of their number to death in the process …. Fleeing, it seems, from what was far less frightening than the bloody fracas they were already in.

I had to read the scene twice to make sure I was not missing something. I thought perhaps some vision of horror was looming up behind the dying clerk so terrifying that even the half-blind, broken-jawed would run, and the one-legged would hop energetically away.

But, no. A room full of screaming warriors were frightened by a screaming unarmed accountant who falls over dead. It simply was not believable.

Conan is left alone in the museum. He steps over the corpse of the clerk, and enters the room holding the horror. A beautiful face peers at him from over the top of a golden screen. It is described thus:

Neither weakness nor mercy nor cruelty nor kindness, nor any other human emotion was in those features. They might have been the marble mask of a god, carved by a master hand, except for the unmistakable life in them—life cold and strange…”

The face calls to him in an unknown language, and Conan beheads it in one stroke.

‘And the Cimmerian came, with a desperate leap and a humming slash of his sword. The beautiful head rolled from the top of the screen in a jet of dark blood and fell at his feet, and he gave back, fearing to touch it. “

Again, I had to read the scene twice to be sure I was not missing something. The face utters a single word, but otherwise there is no immediate threat, no attempt at hypnotic snake-eyes or anything.

He beheads it and hears the thrashing of its decapitated body dying.

‘At last the movements ceased and Conan looked gingerly behind the screen. Then the full horror of it all rushed over the Cimmerian, and he fled, nor did he slacken his headlong flight until the spires of Numalia faded into the dawn behind him … Behind that gilded screen there had been no human body—only the shimmering, headless coils of a gigantic serpent. ‘

Just to emphasize: Our Hero sees the headless body of a gigantic serpent, utterly dead and no threat to anyone, a serpent he himself just killed in one stroke, whereupon he panics and runs away, and keeps running until dawn.

It is a silly ending.

It must be noted that this snake-god only killed the one man who unlawfully and treacherously opened the sarcophagus entrusted to his care. It moved and hid when the police searched, but did not harm them. The clerk died of fright, not due to any malice or aggression on the part of the snake-god. The police ran away due to being frightened by the clerk’s dying words, as best I can tell. The snake-god made no startling nor sudden moves toward Conan, said nothing menacing, made no attack. It seemed to be a handsome person standing behind a screen, with only the head showing, for goodness’ sake.

Howard in the final line mimics the jejune stylistic trick of leaving a shocking twist or revelation for the last line of the last paragraph. HP Lovecraft also was known to indulge in the shock curtain line.

Here it is spectacularly unconvincing, because the shocking revelation had been revealed pages before. The clerk figured out the sequence of events in the middle of the story, and was yelling them to the disbelieving police sergeant, who cuffs him in the mouth. The text reads:

Dionus was a materialist, with scant patience for eery speculations.

So the reader knew what was in the bowl from before page one, if he saw the title of the tale.

Unlike the other eldritch horrors and slithering shadows and antiquarian horrors peopling all other Conan stories, this was particularly unhorrific, far less threatening or eerie than, for example, an ancient vampire-queen or man-eating ghoul, an ape or neanderthal who mimics human warfare or human sacrifice. To be honest, a polar bear would have been a more alarming foe, or a rabid dog.

In preparation for this column, I came across the comic book adaptation of this story.

Roy Thomas, the writer, added and adapted several elements, including turning the young fop into a scantily-clad hot-blooded beauty whom Conan saves from wolves and orders into the museum to steal the sarcophagus. In his version, rather than being killed by Conan, the half-naked beauty is menaced by the snake-god, the watchmen flee like cowards, and Conan battles the monster for three or four action packed pages trying to save her. Moreover, the entire plot of Demetrio police procedure is curtailed, since the beauty tells Conan the backstory of the sarcophagus before directing him to steal it.

All this pulse-pounding action was invented by Roy Thomas, not Robert E. Howard. In this version, Conan flees in fear, but only because the apparition of Thoth-Amon, immortal necromancer-king, appears in the empty sarcophagus to see the results of his murder attempt, and his glowing eyes fall on the barbarian who thwarted him…

All these are changes Farnworth Wright could have told Howard to make in the original, as they eliminate half the minus marks against it.

But for all this, I do not think God in the Bowl is meant to be a detective story at all. The clues are too obvious, and the police even see the murder-monster wrapped around an upper pillar, and mistake it for a thick length of cord.

I think Robert E. Howard meant this to be Conan’s introduction to the reader.

And what must an introduction contain? Two things. A description, and theme; or, in other words, what the man is, and what the symbolizes.

Here is his description:

“… a tall powerfully built youth, naked but for a loincloth, and sandals strapped high about his ankles. His skin was burned brown as by the suns of the wastelands, and Arus glanced nervously at the broad shoulders, massive chest and heavy arms. A single look at the moody, broad-browed features told the watchman that the man was no Nemedian. From under a mop of unruly black hair smoldered a pair of dangerous blue eyes. A long sword hung in a leather scabbard at his girdle.”

Vivid, stark, memorable.

As for symbolism, in this brief one-act, one-scene tableau, we see the forces of civilization, either directly or by their works: the wizard operates by black magic, and seeks to assassinate his foe by treachery, pretending friendship; the rich man betrays the trust bestowed on him, breaking open cargo in his care in a fit of delusionary greed; moreover, the clerk reveals that the rich man meant to frame the night-watchman for the theft, and send his loyal hireling to grisly death by torture; the foppish princeling is willing to betray his hireling, Conan, merely out of convenience to himself; the inspector is more than willing to betray their offices, frame the innocent, and protect the guilty, provided one is poor and the other is rich; the sadistic sergeant merely has his men beat confessions out of whomever is convenient.

The only two decent men in the scene are the chariot-driver, who is a debt-slave who rejoices with ghoulish glee when he learns his master is dead, and the night-watchman, whose only flaw is that he is useless in a fight.

From high to low, wizard, aristocrat, rich man, clerk, charioteer, inspector, sergeant, policeman, slave, all are reprehensible people, either treacherous and cowardly, or cowardly and treacherous.

And, of course, the law is one-sided. In one well-worded touch to display the moral decay of the city-dwellers, a police thug brays:

“Remember the law, my black- haired savage—you go to the mines for killing a commoner, you hang for killing a tradesman, and for murdering a rich man, you burn!’

Conan, at least, will not betray his partner in crime. He would have gone silently to the mines had the fop not backstabbed him to his face, as it were. But that is the sole virtue the savage displays. He is brave, perhaps, but half that bravery seems to be raw animal fury, and half mere ignorance of when he is under threat.

So the theme of what all Conan stories is meant to portray is here displayed nakedly: a contempt for the corruption of civilization.

Other stories glamorize the barbarism of Conan and make it palatable. Here it is not.

Had I read this little story not knowing who Conan was, I would have been left with a very unpleasant impression of a superstitious and stupid brute, too dumb to know that night watchmen are there to raise the alarm, too stubborn to run when he is threatened, too brutal to feel pity or remorse, and frightened of a snake he himself without any particular effort or struggle had just killed.

It is very odd for me to read this first story only after the end of all the others, because the Conan theme of glorifying barbarism only works if the author carefully emphasizes the virtues of the savage while downplaying his vices.

Here, Robert E. Howard is much to honest. The loveable rogue or noble savage, if portrayed in too clear and honest a light, is merely a rogue and a savage: repellant, ignorant, rank, foul, and repulsive.

This is a very sad beginning to a long line of otherwise glamorous, if false, works of adventure fiction. There is no real adventure here, just a bitterness issuing from the pen of Robert E. Howard that is unsightly and disturbing to witness.

In candor, I can recommend this story only for completists seeking every scrap of Conan to read.

It contains little of the robust action for which Conan was later known, and nothing of his valor or nobility. The uncanny atmosphere so needed for a Conan tale is but clumsily portrayed, and the great barbarian himself is neither interesting nor memorable under Robert E. Howard’s inexperienced pen.