Review: Encanto Fails to Enchant

Encanto (2021) is from Disney studio, not Pixar, and comes very close to being one of their animated masterpieces, but fails due to simple errors any competent editor would have seen and fixed in the first draft of the script.

The error here is that the show tells rather than shows every significant point of character development. Resolutions are presented with insufficient set up, or none, are followed by insufficient follow-through, or none. This happens not with one character, but all.

It is mildly astonishing that projects of this size, expense, and prestige can be carried to conclusion without anyone involved seeing and correcting so basic a flaw in story-telling.

But, to be fair, even a near miss for a studio with a history of producing legendary and immortal works of animation puts this film way above average, and it still earns my recommendation.

It is a good film. It could have been great, but missed the mark.

I had heard that this film was insufferably politically correct from certain reviewers I otherwise trust, and had no interest in seeing it when it first came out.

As it happens, I should not have trusted those reviewers.

To be sure, it has all the earmarks of a politically correct bit of goodthink propaganda: No Anglo-Saxons, all males either bumbling or subservient or both, all female characters are strong, in one case physically. The married couples are mixed race, making the children different skin-shades. All these elements please the thought police.

I am happy to report that these elements are organic and unobtrusive: indeed the sad backstory and the plot resolution centers around the lack of the family patriarch, whose role must be taken, for three generations, by his widow, raising her triplets alone.

Hence, although the film makers do not know it, the story is actually about the imbalanced life produced when matriarchs attempt the patriarchal role: they become the symbol of motherhood gone wrong, which is to be overprotective, and destroy the very house they raise.

The conceit of the film is this: in an isolated valley in Central America, three generations of a family inhabiting a magical manor house are each granted a miraculous gift or magic power, which they use, at the direction of the clan matriarch, for the benefit of the surrounding villagers, out of gratitude for the miracle bestowed.

In the central window of the main hall burns an inextinguishable candle, looking remarkably like a Roman Catholic prayer candle, which first led the grandmother Alma, and the entire village of refugees, to this valley of refuge. The candlelight built the manor house and raised the surrounding mountains to isolate the valley from the surrounding world.

The manor house, naturally named Casita, albeit voiceless, is one of the more vivid and delightful characters in the film, for it can move floortiles, open and close doors and cabinets, drop and raise balconies or turn staircases into slide, which it does with a particularly puckish humor.

When a child of the magical family, naturally named the Madrigals, grows to the age to leave the nursery, the house creates for him a new doorknob, door, and room beyond. Passing through the threshold grants the child his gift: to heal the sick, see the future, control the weather; to command the strength of Hercules or have hosts of flowers bloom; to mimic anyone’s look or to hear their every softest sound, or to talk to animals.

The new room granted, like the many-dimensional police call box of Doctor Who, is bigger on the inside than outside, and may contain gardens, jungles, deserts of sand, a miniature landscape.

In the opening sequence is a clever bit of maid-and-butler dialog made into a song where Mirabel explains to three cute ragamuffins the names and powers of her extensive clan.

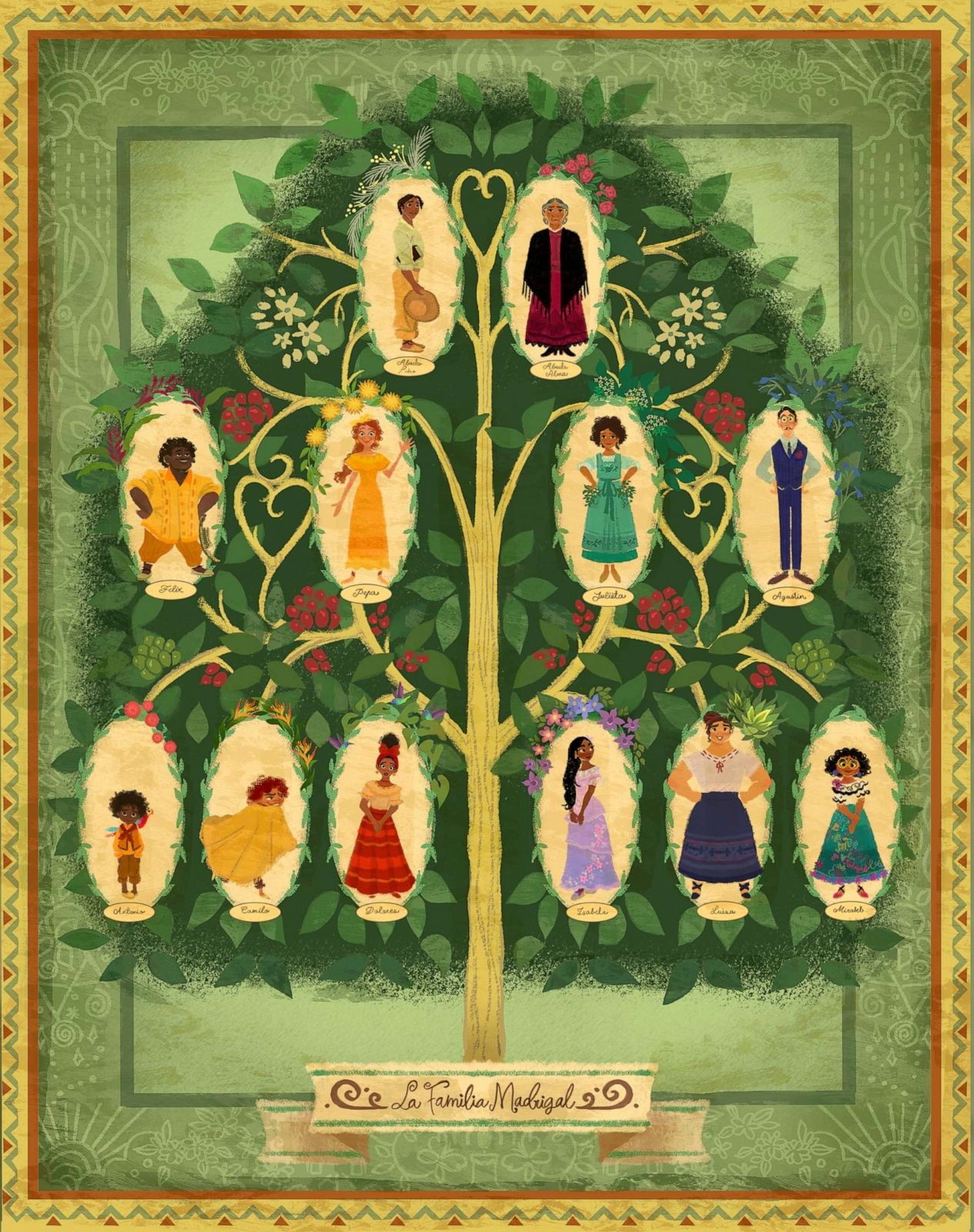

It is not easy to bring one grandmother, mother and father and uncle and aunt and her husband onstage, two sisters, three cousins: an even dozen characters, if one counts the dead grandfather. But the film here performs the feat gracefully and swiftly.

Only Mirabel has no gift. Her magic door evaporated under her hand on her seventh birthday, and, now, at fifteen, she still sleeps in the tiny nursey.

The awkwardness and sorrow of being a muggle in a family of supers is well handled and properly three dimensional. In words, her parents reassure her that she needs no special gift to be special in their eyes; meanwhile, in practice, there is not much an awkward teenaged girl can do without getting in the way. In words, she is cheerful and without envy; meanwhile, in practice, her life is consumed with waiting for a miracle that comes for others, never for her.

When her young cousin is granted a particularly impressive gift, proving the tradition of miracles will continue without her, Mirabel is ignored, and left out of the family photo.

Mirabel, dejected, steps outside, where she beholds in horror tiles crumbling from the roof, the foundations breaking, and cracks growing in the walls of the beloved house.

But when she rushes back into the party, shouting warnings, her family accuses her of attention-seeking, hallucination, or fibbing — for all the cracks and damage are vanished ere any other witness sees.

Mirabel is stung by these accusations, but, later, overhears the Grandmother praying to her dead husband. The grandmother knows the house is cracked in the foundations, and is likely to fall, and she prays her family never learn how fragile the miracle granting their magic powers truly is.

At this point, for me, the film went from good to great, because the plot was not how the muggle girl reconciles herself to living among X-Men as an inferior, nor about how she can learn to gain the magic never granted to her; rather, the plot was now about the secret origins of the miracle, and the mask of silence and denial the grandmother is using the hide that secret.

Mirabel now sets about to investigate if and how the family miracle is eroding, and what can be done to preserve it. Had there been a real answer to this puzzle, the promise of this great scene would have made for a great film. Instead, there is a half-answer, which sorts of answers the question, but not really.

Seeking answers, Mirabel speaks to her cousin Dolores who can, like Math Mathonwy of old, hear every word whispered on the wind; who tells her that the Amazon cousin Luisa is nerve-wracked; Luisa, in turn, reveals that her Amazonian strength is diminishing when the wall cracks appear; sending Mirabel to the abandoned tower of her uncle Bruno the visionary; who fled into hiding when his visions revealed the coming doom of the house.

Mirabel discovers the vision centers on her, either to topple the house or save it; and that way to save the house is very simply to give her perfectly beautiful flower-power older sister Isabela a hug, which she does.

While trying to hug her perfect sister, we discover that Isabela wants to make cacti, not roses, nor marry the bridegroom grandmother selected for her. Isabela want to throw paint-bombs made of colored pollen and make a mess.

All of which angers the grandmother, who then quarrels with Mirabel, and the house collapses anyway.

There are three or four show-stopper songs, one of them “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” is extraordinarily charming and well-executed, all in the best tradition of Broadway tune, except for two things:

First, the lyricist (Lin-Manuel Miranda of HAMILTON fame) is too clever by half, attempting intricate asymmetrical stanzas and internal rhymes or half-rhymes which neither scan nor form recognizable rhyme-patterns. There are no repeated refrains. These are not songs one can hum.

Second, the songs contain all the character development, none of which is established in the surrounding plot.

The central flaw of this film, the reason why it is merely good and not great, is that we are told, nor shown, what the main personality difficulty of each sister or cousin might be, and then it is either resolved on the spot the moment it is named, or nothing comes of it thereafter.

For example, Isabela the flowery sister’s worry is that she tires of the role of being always pretty and well behaved, and wants to create new things and do new things. While arguing with Mirabel, Isabela accidentally creates a cactus rather than a rose, and bursts into song, because her lifelong problem is solved by the realization that she can be whatever she would like to be.

Except that there was either only a slight hint, or none, that this was her lifelong problem erenow. The song was suppose to be a big payoff moment, the revelation of a long build-up — but there is no build-up. One cannot write a satisfactory song about leaping out of the sick-bed, cured and whole, if no mention is ever made of any sickness in the first place.

Likewise, Dolores the eavesdropper cousin in one line of another song mentions being hopelessly in love with a man promised to her sister, and in a second song-line in the finale wins his heart instantaneously so that he proposes matrimony before the end of the lyric. A more abbreviated and more unsatisfactory way to handle a love triangle cannot be imagined.

Likewise, Luisa the Amazonian sister’s worry is that all family burdens are put on her. She is literally shown shouldering the entire weight of the house. Once Mirabel hears Luisa’s secret fears confessed, however, nothing comes of it, until, again, in one line in the finale song, the sisters agree they can rely on each other for help.

Normally, super-women portrayed as physically strong is annoying because it is unnatural. It eliminates the possibility of romance because it eliminates any possibility of being swept off her feet. This particular case, under the particular philosophy of the film, however, should be granted an exception: the physical strength is merely an extended metaphor for the problem many a woman, particularly an older sister, tends to create for herself when she takes on too many burdens.

You see, the film makers wanted to make a film using “magical realism” tropes and elements. For those of you not familiar with this particular subgenre of fantasy, let me explain.

Fantasy includes any story with a magical element. Fantasy differs from science fiction in that the magical element acts by the dream-logic rules of symbolism or theme, not by the literal logic of a scientific gizmo in a science fiction story.

This is why Frodo Baggins from J.R.R. Tolkien need not doff his clothing to be invisible, whereas the Invisible Man from H.G. Wells must. The corruption issuing from the gold ring in Baggins’ case is due to the cursed and evil magic of the forging of the ring; whereas the Invisible Man is corrupt because the logical mind of the mad scientist sees no other useful application of the power of invisibility aside from a reign of terror.

In other words, what is literal in science fiction stories is symbolic in fantasy stories.

Magical Realism make fantasy stories palatable to literati snobs by treating the magical elements in the story as extended metaphors for whatever the symbolic or thematic meaning the magic represents.

Magical Realism blurs a distinction fantasy stories keep sharp, namely, this: within the story, the magic ring really is a ring, it is solid, round, weighty and so on, and the magic power really is magic; whereas outside the story, a magic ring is a symbol of deception, domination, or sin.

In a fantasy story, only love’s first kiss will awaken the sleeping beauty. This kiss may symbolize romance and the young bride’s awakening to the joys of it, but that kiss treated as real in the story, regardless of symbolism: merely blowing a kiss will not do, nor a firm handshake, nor will the loving kiss of a sister, or the licking tongue of a loyal dog.

In magical realism, the magic ring might represent, for example, a wedding vow, with the ring tragically cracking in two upon an act of infidelity, or something of the sort. But the ring is not, itself, independently a ring. It is not a proper prop with its own meaning, origin, fate, or rules.

Magical realism hence takes the symbolic nature that any magical element in a fantasy story by rights should have, and and ties it as closely as possible to the literal thing symbolized, so it no longer acts like magic in a fairy tale. It merely acts like the thing metaphorized.

Magical realism rarely rises above the level of flatfooted allegory. Allegory is the least satisfying form of story telling because it is the least story-like.

In an Allegory, a character named Patience, or example, tells the hero to be patient, and the character named Rash urges the opposite. Men cut themselves on two-edged swords or hoist themselves on their own petards. A baby named Invention in a lab coat and swaddling clothing will be in the arms of his ragged and starving mother named Necessity, and so on.

Allegories are read for the moral instruction of the allegory, or the cleverness of the allegorist, not for the charm of the drama.

No doubt replacing the magic of a fairy tale with the magical realism of a flatfooted allegory assists literati snobs, who are noticeably lacking in imagination, to imagine otherwise fantastical or frivolous spectacles.

But magical realism is a very difficult genre to write in, because it is so very easy to miss the trick.

The trick is that the treatment of the metaphorical element outside the story, that is, the metaphor in the mind of the reader, has to parallel the treatment of the magical element inside the story, that is, the plot element of the events as understood within the story-world by the story-characters in it.

Like any allegorical story, a magical realism story must both make sense as allegory and as story.

By deliberately smudging the line between metaphor and magic, magical realism runs the risk of making no sense inside the story-world, as event does not follow event according to story-world logic, despite making sense as metaphor, according to real-world logic.

This film provides a perfect example of this shortcoming.

In a properly constructed fairy tale, if the vision prophesizes a certain simple, arbitrary-seeming act, such as hugging a sister, will prevent the magic manor house from falling, then doing the act prevents the fall.

Whereas, here the magical manor house is merely a symbol for the family unity, whose foundations are cracking because they are based on the grandmother’s overbearing strictness, which the unhappy younger generation endures unspeaking.

In the climactic scene, hence, the thing that would have solved the problem in a properly constructed fairy tale, namely, following what seems arbitrary direction from a vision, does not solve the problem. The cracks in the family house are allegorical for the intergenerational problems springing from the grandmother’s fears and overprotectiveness. The vision showing how to solve the problem does not solve the problem.

Instead, in a well done scene that is marred because it repeats information already revealed in the introduction, we learn, or, rather, we hear once again, the origin and sad backstory of the founding of the magical manor house, which involves the death of the grandfather.

Then the family and the villagers cooperate to rebuild the manor house, which suddenly, when Mirabel opens the front door, shines with its old magic and comes to life again. And she still does not get a magic power, even though the door opened for her at last.

Roll credits. The end.

The ending makes perfect sense as a magical realism story: the flatfooted allegory is painfully clear and unsubtle as all flatfooted allegories are. The house is the family and the family is the house. Emotional turmoil are cracks in the foundation, leading to collapse; rebuilding the house rebuilds the family, and once unified, the magic of family life returns.

Except that the ending makes no sense whatever as fantasy, as fairy tale, as drama or as morality play.

As fantasy, there is no reason within the story-universe why the dead house would spring to life again since the magic candle that was the source and heart of its life is gone and is not relit.

As fairy-tale, the story never identifies any fairy godmother or saintly intercessor as the source of the magic or miracle, never confirms why it was granted, and hence never says why the magic was denied to Mirabel, or on what grounds it was found again. It literally happens for no reason.

As drama, none of the problems facing the heroine are serious, except, once, when she must improvise a way to cross a deep pit in her uncle’s spooky tower.

Other than that, one character says she is under pressure, but it is never onstage; another says she hide much beneath her smile, but this is never shown; a third says she loves a man on whom she bestows not one glance nor word beforehand; and the grandmother is never shown as anything but loving, if dignified — which is hardly a vice, and a normally a virtue.

As morality play, the double-sided modern moralism requires both that an untalented, plain, and ungifted girl be adored as miraculous, and requires that all gifts and talents be distributed evenly without regard to merit. The modern moralism requires that there be no moral standards, but, instead, the sole moral standard is self-esteem and the sole sin against morality is not realizing one’s own true self-awesomeness.

These two morals cannot cap the same play. The story must either show Mirabel gaining (or show her as having had possessed all along) a magic power equal to those of his relations; or must show those magic powers to be of no worth, as the sole true worth springs solely from one’s own self-esteem and sense of self-worth.

The first option is impossible because the modern spirit cannot have Mirabel resolve her craving for a miracle by accepting her inferior status as a useless muggle, not even pretty enough to make for a good political marriage. For moderns, pride is good and humility is humiliation. That implies hierarchy, which is anathema.

The second option is impossible because, likewise, the modern spirit cannot have Mirabel resolve her problem by hard work, learning the secret of the origin of the magic, and passing whatever test one needs pass to be worthy. But that implies meritocracy, which is anathema.

So the movie simply does both and neither. Mirabel sings about how she now sees herself and only herself. Perhaps she has achieved perfect satanic pride, and total self absorption. The danger of a story preaching humility is avoided.

Then she is given a doorknob and door in any case, and magic gushes forth and floods the newly rebuilt house, but there is nothing, no after credit scene, no hint, no line of dialog, to indicate whether Mirabel actually as a gift now or no. The danger of a story preaching meritocracy is avoided.

In so doing, all the moral theme which might have been in the story are avoided. There is no villain, no real problem, no love triangle, no irreconcilable conflicts. Instead, there is, at most, a tiff or a sadness caused by an ordinary, daily level of life’s imperfections. That is all.

Even the exile of Bruno was not a problem, in that he was sent away, or sent himself away, but did not go, so all that is needed to bring him home is a hug.

Problem solved.

Then they all flatter and praise Mirabel for having done nothing in particular.

Isabel, laughing in her new found friendship with Mirabel, calls her a bad influence: except that she is not. She did not influence Isabel’s desire to grow cacti in any way. The feud between them was not even a kerfuffle. It was not anything, not based on anything, and when it is resolved, it is effortless hence meaningless.

It is unclear how much of this is due to the particular moral weaksightedness of the modern age, and how much was due to a fumbling attempt at the Magical Realism genre. Let us say only that Magical Realism makes moral weaksightedness far too easy to fall into.

Literati snobs who claim to like magical realism as a genre are much easier to cheat than children hearing a fairy tale in a nursery. Fairyland logic is harsh and unimpeachable: if only love’s first kiss will resurrect the dead Snow White, it is a cheat to have a hug from Snow White’s sister Rose Red suddenly able to perform the same miracle.

Cause follows effect with the same iron inevitability in elfland, beyond the fields we know, as here on earth, if not moreso. What makes elfland elfish is not that anything can happen — that is most clearly not the case — but that the causes of wonders are hidden from mortals — as they are on our world — until and unless they are revealed by the riddle, a prophet, a dream, a benevolent spirit, or, as in our world, in the writings of an ancient book reporting riddles, prophecies and dreams inspired by the spirit.

So it is an unsatisfactory ending if the hugging of the cruel older sister does not stop the fall of the house, despite that the vision said it would. It is unsatisfactory if the house is not a living spirit of its own, above and beyond being merely a flatfooted allegory for the unity of the family.

The magic of Mirabel opening the door at the end should have granted her, at long last, the magical gift that was hers, and it should exist both in the story as a story element (let us say, the ability to repair cracked and damaged things at a touch) as well as being an allegorical element outside the story, showing how her perseverance exposed the hidden cracks in her family unity and cured them.

Or if she were to continue with no gift, that should have been explained as well, and made clear why the house (or whatever angelic and elfish power was behind the house) willed it to be so. But it needed to be addressed and answered within the story, not as a cheat which even the loose rules of Magical Realism should not excuse.

Nonetheless, witty, charming, heartwarming, fun, with a bland and boring but non-offensive moral message praising family life and self-esteem, ENCANTO is a good and workmanlike product from Disney, and could have been great, but is not.

Enchantment come from showing, not telling. Showing draws the viewer into the world of imagination, and allows him to dwell there, refreshed. Telling merely informs him that others, in theory, have done so.

ENCANTO had all the elements necessary to brew a love-charm, but recipe was not followed, and so the enchantment is lost.

But the film still holds charm, and is well worth seeing. Is it not Disney’s best effort, but it is above their average.