Review: Belle (2021)

Belle is a 2021 Japanese animated film written and directed by Mamoru Hosoda and produced by Studio Chizu. It came to my attention because the musical soundtrack has a haunting simplicity and beauty unlike anything made in the modern day.

I recommend it, and strongly, but only for those attracted to melancholy and sentimentality. This is a girlish story, so men without daughters may be uninterested.

It is not as good as the work of Hayao Miyazaki, but it is good enough to invite comparison.

This film is billed as a science fantasy, which is not what I would call it.

The film is a coming of age melodrama about a shy and grief-stricken schoolgirl coming to the aid of a shy and grief-stricken stranger she meets by chance in cyberspace.

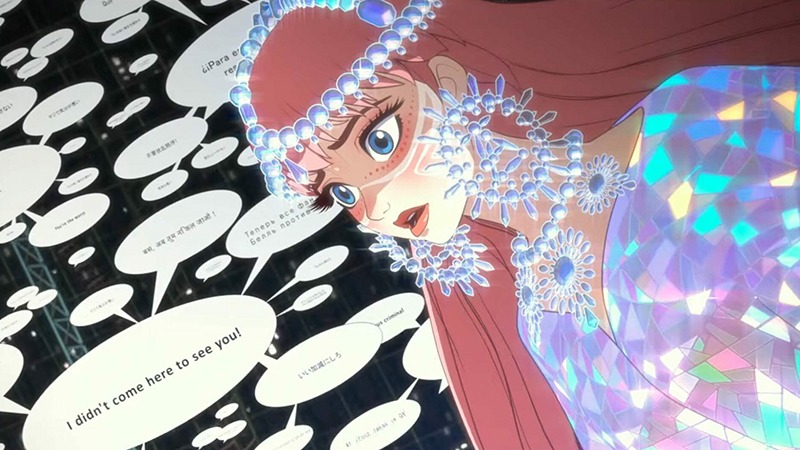

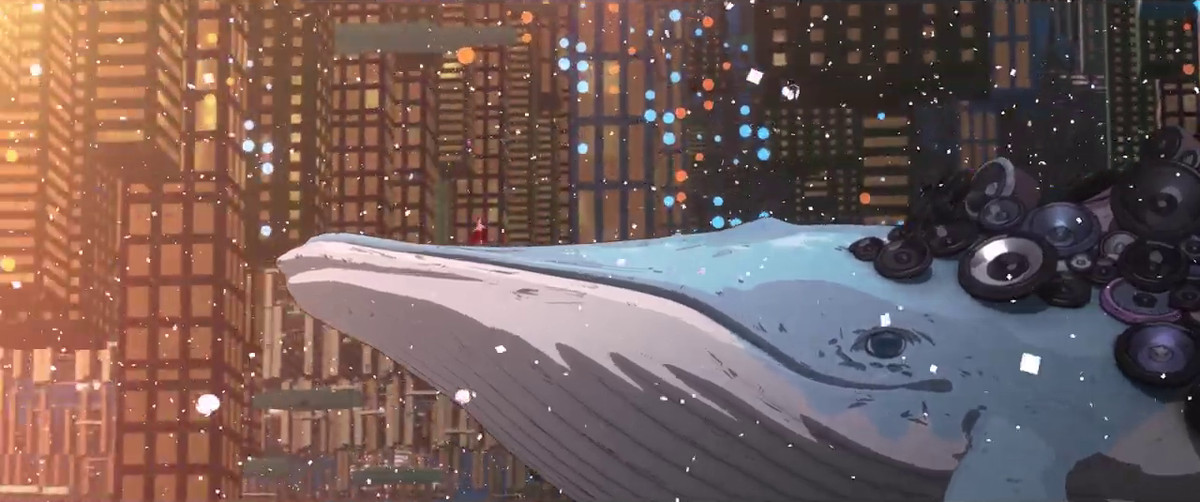

The depiction of the avatars and props in the computer world is a tour-de-force and a visual delight, drawn with a vibrant palate.

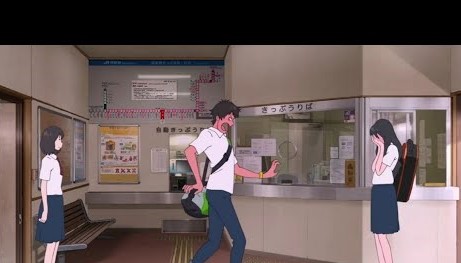

Roughly half the film takes place in cyberspace, which is gorgeously animated and makes the film worth seeing on the big screen. The other half takes place in gorgeously animated small-town Japanese countryside.

The only science fictional element present is the idea that cyberspace is more fully immersive than what we have now, so that, for example, if one’s real body is being beaten in real time, the damage is reflected or represented in one’s online avatar. One’s avatar is unique, based on an algorithm taken from biometric login information. So, as for as science fiction technology goes, this story could take place tomorrow in America, or, in Japan, yesterday.

The art direction in scenes concerning the Beast form a deliberate homage following Disney’s BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (perhaps as turnabout for Disney’s homage to KIMBA THE WHITE LION) but the plot and theme are unrelated. That was a romantic love story; this story is about compassion.

The other theme present is the ironic disjunction between the shy, plain-faced and humble protagonist, and her invented online persona, who is a glamorous world-celebrity. The main antagonist in this film is a self-appointed unmasker or doxxer, who ruins online lives by revealing the avatar user’s real appearance beneath.

The plot concerns a schoolgirl named Suzu (which is the Japanese word for demon-banishing hand-bells) who, after the tragic death of her mother, lives with her father and her crippled dog, speaking rarely, eyes always downcast. She has lost the will and ability to sing. Inventing an online avatar named Bell, and finds that, in the imaginary world of cyberspace, she can sing freely and from the heart, so much so that, after being initially scorned, her song go viral. Aided by her cynical but tech-savvy friend Hiro, she gains immense fame.

One of her concerts is interrupted by an avatar called Beast (or Dragon) who is an unbeatable but unlikeable character from the fighting-game side of cyberspace. He is being chased by a self-appointed group of vigilantes eager to unmask him, and force him offline out of shame.

Suzu is intrigued by the dark, ugly stranger who is a rebel who plays by his own rules, and wonders at what inner demons of sorrow he is wrestling. She searches for his identity while trying to avoid the vigilantes harassing him and following her.

Meanwhile, in real life, Suzu’s popular and attractive friend Ruka wants to confess her true feelings to a boy on whom Suzu (unbeknownst to her) also has a crush; meanwhile another boy, toward whom Suzu has no feelings, expresses his feeling to her — but whether he was sincere or just joking is unclear.

If this kind of awkward and silly, shy schoolgirl soap opera is your cup of tea, dear reader, there is who bucketload awaiting you.

Myself, I was delighted.

There is a scene where one cute, cripplingly-shy Japanese schoolgirl is standing with her hands over her face, unable to peek, while another cute, cripplingly-shy Japanese schoolgirl is trying to maneuver a shy schoolboy into confessing his true feelings to her, while a second boy, shy but grim and stoical, looks on, but he will in time reveal his true feelings, when duty permits.

This was truly one of the cutest scenes I have ever seen, but watching it may lower male testosterone levels. You may need to watch some Alaskan wilderness survival drama where Jack Reacher or Conan the Barbarian fights a polar bear to return to normal.

The ending was also girlish, and any viewer expecting something more final or definite will be disappointed. The true beast in this film is not the Beast, but an abusive father. Nothing is resolved with him, but he is faced down, and so his loss is spiritual, not physical, almost invisible. Whether anything permanent will change is unclear.

Such is the different between male and female drama.

In a man’s drama the plot is not resolved until the problem is solved, and the prone foe is bleeding or dead at the hero’s feet. In a girl’s drama the plot is resolved once an internal change, a spiritual change, takes place in herself or, inspired by her, in those around her. Such a change takes place when heroine is firmly committed to aid or sustain a cause or a friend or a lover, or, in a tragedy, when such a commitment is betrayed or lost.

Such is the nature of feminine decision-making. Feminine decision-making is personality-oriented. It is like deciding to get married: which is not an action that has an end and a result, but a life devoted to another. Masculine decision-making is task-oriented, like deciding to rescue the girl, kill any rivals, and carry her off as a prize. You win; the other guy loses.

In sum, a feminine drama is over when she decides to take a vow, because this changes her internally. Feminine work tends to be cyclic and ongoing, so it has no end-date. A masculine drama is over when he succeeds or fails to fulfill the vow, because he either meets the thrill of victory or a agony of defeat. Masculine work tends to be like a wager of battle, with a definite end-goal.

Oddly, this version of BEAUTY AND THE BEAST has no hint of romance between the two. The relation is purely platonic, based on mutual sympathy. The romantic male in this film, who is a minor character, does not even open up the possibility of courtship until the last scene. As explained above, this is a feminine dramatic point, because it is the decision to begin, not the moment of victory or failure.

Nonetheless, I was deeply impressed with this scene, because the young man was unwilling to pay court to the girl, despite his hidden feelings, until he knew his other duties to her were complete. This displayed a simple sense of honor rarely depicted in stories these days.

By being so completely feminine in its theme and plot, BELLE avoids the recurring errors that haunt any cyberspace story, or “trapped on the holodeck” episode. A similar error haunts any story taking place in a dream. Namely, even within the context of the story, cyberspace is not real. No one can actually suffer wounds, bruises, or death.

Many a tale attempts to circumvent this limitation by establishing that the events and the dream-world or cyber-world, if sufficiently damaging to one’s image or avatar, will drive the real man mad, or traumatize him, or erase his brain, or the system biofeedback will kill his sleeping body. Shifts and conceits are attempting to make what essentially must be a purely mental or spiritual drama into a physical drama. Even when successful, it is awkward.

Whereas, if the story is already a feminine melodrama, the stakes at risk need not involve bloodshed, life or death. Women do not defeat women by brute violence, but by destroying reputations, by backbiting, by false friendships, by shame and embarrassment. At stake is shame or honor, being popular or being ostracized.

In a female drama, gossip is a battle. See, for example, how the female elephants treat Dumbo’s mother in the Disney film of the same name. A real battle is impossible in cyberspace, because no one can really get hurt. Whereas a gossip-battle lends itself easily to a cyberstory, particularly because the normal hindrances to gossip are not present, for all are anonymous.

For a like reason, if the drama is whether a secret is kept or revealed, this is a girlish concern. Manly men do not deal with secrets, except for priests, doctors, lawyers and spies, and, even at that, spies are dishonorable creatures, because they tell lies for a living.

But a woman who cannot keep a secret cannot keep a friend.

In cyberspace, the drama of keeping or betraying a secret, the drama of being doxxed, is emphasized, because the whole world can be told at once, and there is almost no hope of mitigation or retaliation.

Almost. One of the finer scenes in this film, and one which brought a lump to my throat, was when such a betrayer paid a price for his doxxing attempt, and, instead of turning on Suzu, the whole world joined her in a song of sorrow and hope meant to find the missing Beast.

There are no wounds in cyberspace, but there are emotional wounds, which is precisely the type of trouble women deal with more than men, and are more apt to deal with.

So having seen half a hundred unconvincing attempts to make holodeck stories seem dramatic, finally seeing one that, merely by putting all things in a feminine light, succeeds where others have failed, is a pleasure.

And the thing looks and sounds gorgeous. Even if girlish soap opera is not for you, seeing the film just to hear the songs may yet be.