The Golden Age Ep. 02: The Age of Saturn

Episode 2

The Age of Saturn

He wandered far, to a place he had not seen before. Beyond the gardens, in an isolated dell, he entered a grove of silver-crowned trees. He paced slowly through the grove, hands clasped behind his back, sniffing the air and gazing up at the stars between the leaves above. In the gloom, the dark and fine-grained bark was like black silk, and the leaves had mirror tissues, so that when the night breeze blew, the reflections of moonlight overhead rippled like silver lake water.

It took him a moment to notice what was odd about the scene. The flowers were open, even though it was night, and their faces were turned toward one bright planet above the horizon.

Puzzled, Phaethon paused and pointed two fingers at the nearest trunk, making the identification gesture. Evidently the protocols of the masquerade extended to the trees as well, and no explanation of the trees, no background was forthcoming.

“We live in a golden age, the age of Saturn,” said a voice from behind him. “Small wonder that our humor should be saturnine as well.”

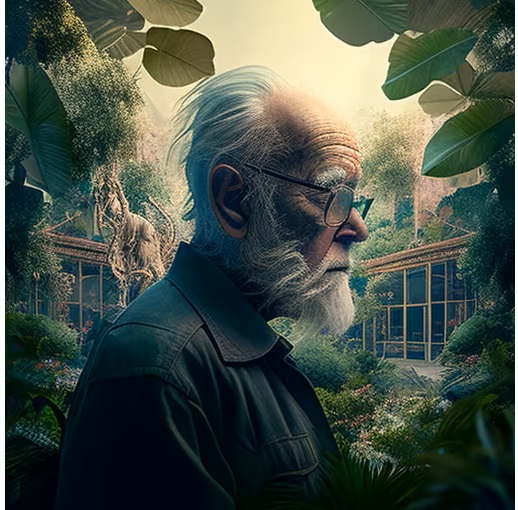

One who appeared as a wrinkle-faced man with white hair and beard, wearing a dark robe, stood not far away, leaning on a walking stick. During masquerade, Phaethon had no recognition file available in mind, and thus could not tell what dream-level, composition, or neuroform this old man was. Phaethon was not sure how to act. There were things one could say or do to a computer fiction that a real person, a telepresence, or even a partial, would find shockingly rude.

He decided on a polite reply, just in case. “Good evening to you, sir. Then there is a hidden meaning to this display?” His gesture encompassed the grove.

“Aha! You are not a child of this present age, then, since you seek to look below the surface beauty of things.”

Phaethon was not certain how to take this comment. It was either a slight against the society in which he lived, or else against himself. “You suspect me to be a simulacrum? I assure you, I am real.”

“So simulacra must seem to themselves, I suppose, should anyone ask them,” said the white-bearded man with a wide-armed shrug.

Then he seated himself on a mossy rock with a grunt. “But let us leave the question of your identity—this is a masquerade, after all, and not the right time to inquire, eh?—and study instead the instruction of the trees here. I do not know if you detect the energy web grown throughout the bark layers; but a routine calculates the amount of light which would shine, and the angle of its fall, were the planet Saturn to ignite like some third sun. Then, true to these calculations, the energy web triggers photosynthesis in the leaves and flowers, and, naturally, favors the side and angles from which the light would come, you see?”

“Thus they bloom at night,” Phaethon said softly, impressed by the intricacy of the work.

“Day or night,” the white-bearded man said, “provided only that Saturn is above the horizon.”

Phaethon thought it ironic that the white-haired man had picked Saturn as the position for his fictitious new sun. Phaethon knew Saturn would never be improved, the huge atmosphere never be mined for volatiles. He himself had twice headed projects to reengineer Saturn and render that barren wasteland more useful to human needs, or to clear out the cluttered navigational hazards for which near-Saturn space was notorious. In both cases public outcry had halted his efforts and driven away his financial support. Too many people were in love with the majestic (but utterly useless) ring-system.

The white-haired man was still speaking: “Yes, they follow the rise and fall of Saturn. And—listen! here is the curious part—over the generations, the flowers have evolved complex reactions so that their heads can turn to follow that wandering planet through cycle and epicycle, opposition, triune and conjunction. Thus they thrive. They are not one whit disaccommodated by the fact the sun they follow with such effort is a false one.

Phaethon looked back and forth across the grove. It was extensive. The cool night breeze tingled with the scents of eerie mirrored blossoms.

Perhaps because the man looked so odd, white bearded, wrinkled, and leaning on a stick, just the way a character from an old novel or reproduction might look, Phaethon spoke without reflection. “Well, the artist here did not use flint-napped knives for his gene-splicing, and he didn’t run his calculations in Roman numerals on an abacus, eh? Rather a lot of effort for a pointless jest.”

“Pointless?” The white-haired man scowled.

Phaethon realized his blunder. Perhaps the man was real after all. Probably he was the very artist who had made this place. “Ah … Pardon me! ‘Pointless,’ I admit, may be too strong a word for it!”

“Oh? And what is the right word, then, eh?” asked the man testily.

“Well, ah … But this grove is meant to criticize the artificiality of our society, is it not?”

“Criticize?! It is meant to draw blood! It is Art! Art!”

Phaethon made an easy gesture. “No doubt the point here is too subtle for me to grasp. I fear I do not understand what it means to criticize civilization for being artificial. Civilization, by definition, must be artificial, since it is manmade. Isn’t ‘civilization’ the very name we give to the sum total of manmade things?”

“You are being obtuse, sir!” shouted the odd man, drumming his cane sharply into the moss underfoot. “The point is! The point is that our civilization should be simpler.”

Phaethon realized then that this man must be a member of one of those primitivist schools, whom everyone seemed to revere but no one wanted to follow. They refused to have any brain modifications whatsoever, even memory aids or emotion-balancing programs. They refused to use telephones, televection, or motor transport.

And some, it was said, programmed the nanomachines floating in their cell nuclei to produce, as years passed, the wrinkled skin, hair defects, osteoarthritis, and general physical decay that figured so prominently in ancient literature, poems, and interactives. Phaethon wondered in horror what could prompt a man to indulge in such slow and deliberate self-mutilation.