Review: Disney’s ROBIN HOOD

There is no Disney animated feature film so bad and boring that it is not someone’s favorite since childhood. Even the worst have some redeeming qualities.

And this is, so far, the worst.

Robin Hood as a red fox is inspired, well drawn, and a delight to see, but little else in the film is.

ROBIN HOOD suffers badly from the flaws that begin to afflict all the company’s work during the dry period after JUNGLE BOOK, namely, the lack of thematic unity, of plot motion, of memorable characters, of high-quality draftsmanship. These stories are larded with silly slapstick and shallow schmaltz, and deflated by comedically non-threatening villains.

The one original conceit of the film is that the animals have their own version of the legend, one peopled with beasts from European woodland, Indian jungle, African savanna. Alan-a-Dale, here a rooster with a hicktown southern accent, will tell the tale in a folksy and utterly non-English fashion. The characters are then introduced by their species.

And we discover it is the cast of the JUNGLE BOOK playing dress-up.

Balou as Little John looks the same and voiced by the same voice-actor, the great Phil Harris. Kaa plays Sir Hiss, and even given the same hypnotic multi-colored eyeball powers as Kaa, except that, aside from a passing reference that Kaa used this power to send Richard the Lionheart off to the Crusades, it is never used.

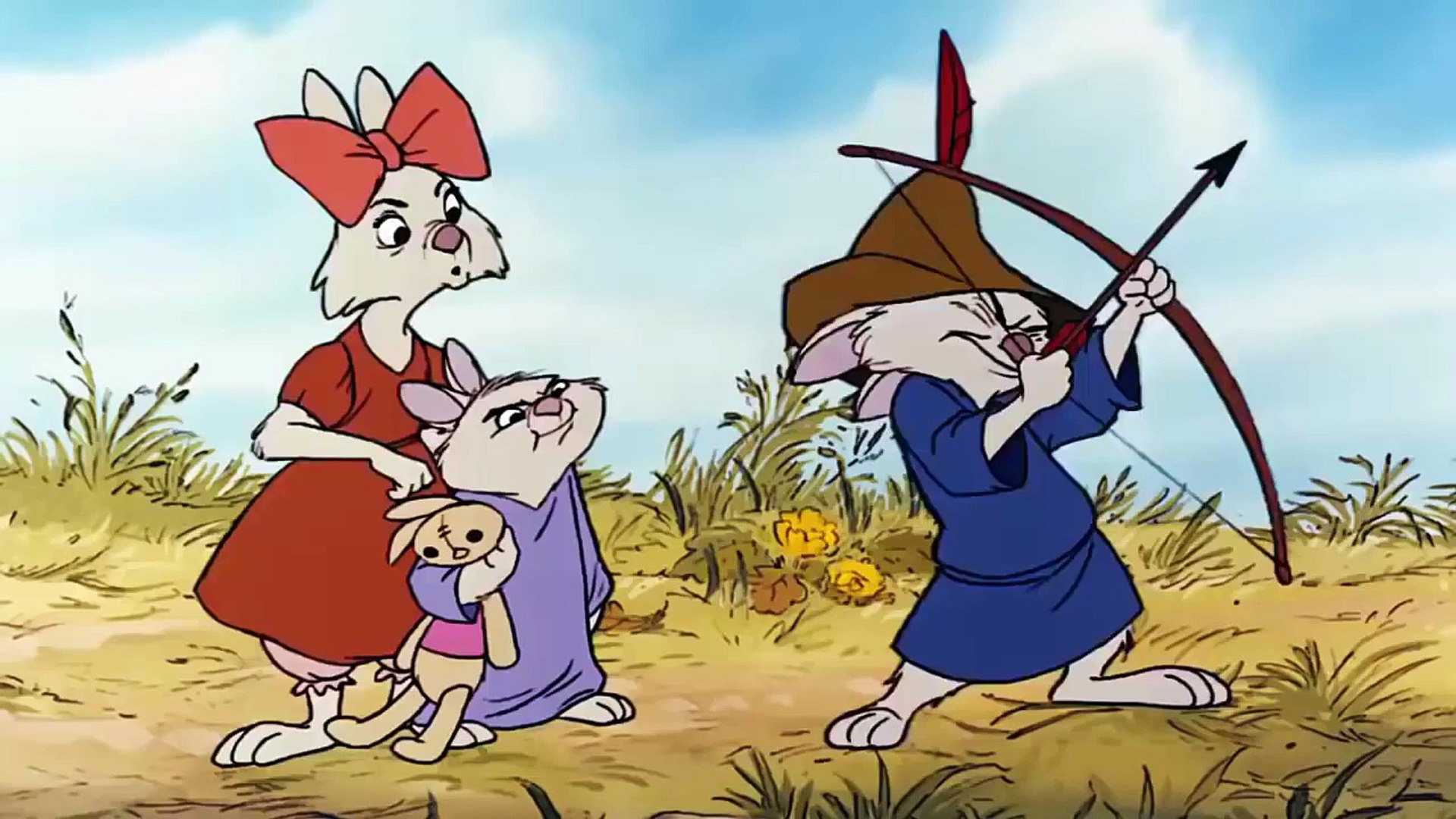

The children of the townfolk are bunnies and a tortoise, and take up much screen time being adorable, idolizing Robin, while as yet Robin had not done anything on screen worthy of admiration.

Robin gives one of the bunny children, Skippy, his hat and bow. Nothing comes of this.

This strange sense of having the viewer walk into a story that already took place offstage plagues nearly every scene.

The fact that Disney’s venture into the legend of Robin Hood borrows elements from the iconic 1938 Errol Flynn version rather than finding older and more original sources sets up a sad contrast in any fan familiar with both films. The comparison is fatal. Every scene is taken directly from some corresponding scene in the Errol Flynn original, except portrayed without context, without energy, wit, or effort put into it.

The Disney film limps along without any plot elements being properly set up or followed through in a strangely amateurish fashion, as if the writers expecting the viewer already to remember and recognize the scene from Errol Flynn, and fill in the blanks from his own imagination.

Indeed, the Disney film is like one of their famous theme park rides: the moving chair carries the audience past lively scenes of Caribbean pirates or haunted mansions merely to show off the animatronic cleverness of moving dioramas depicting stock scenes from tales already familiar and well loved. No tale is actually told.

The story of Robin Hood actually never comes on stage in the Disney film: it is merely a given. At the beginning, he is already famous for being an uncatchable highwayman, expert archer, and woodsman, and Little John, Friar Tuck, and his other Merry Men are already old friends of long standing. There is no quarterstaff fight on a narrow bridge, no dunking, no pranks, and no brawl as Robin meets and wins over his men to his cause.

Likewise, Maid Marion is already in love with him. There is no tension, no romance shown, as the matter is already accomplished. When she is introduced, in a bit of long and boring dialog with her lady in waiting, here an overweight chicken, she is already worrying and waiting for Robin to propose marriage, but, as if Disney forgot how to tell a love story, no slightest obstacle to the marriage is ever presented, aside from a mild and unexplained reluctance on the part of Robin, which he reveals to his friends in another bit of long and boring dialog.

Friar Tuck the badger then announces out of the blue that there will be an archery contest, and Robin is wild to go: but the viewer is merely expected to know that Maid Marion will kiss the winner, and that Prince John means to spring a trap.

In the Errol Flynn version, all these things are neatly set up in scenes that also show Marion’s growing affection for Robin, and the growing hatred of his rival and enemy, Sir Guy of Gisborne.

Here, Maid Marion is in no apparent danger of suffering arrest, nor is clear whether or not Prince John is unaware of her affection for Robin, nor is Robin in the slightest danger when he goes in disguise to the contest, as a fat hen (Marion’s Lady in Waiting) can defeat all the guards and men-at-arms handily in a long, drawn-out series of slapstick escapades, where tents and armies are flung hither and yon, towers knocked aside, brick walls smashed through.

Or perhaps he does get caught in this scene: it is impossible to remember, since nothing happens for any reason in the film. Everything happens because there was a parallel scene in the Errol Flynn version.

Likewise again, the suffering of the common man under Prince John’s taxes are alluded to, but the only moneys shown being collected are a single coins from small children, from a dog in with a broken leg, or from the church poor box.

Likewise again, the villainy of the villains is merely assumed. Onstage we see Robin Hood dressed in drag as a gypsy defrauding (but not robbing) Prince John, who has been abundantly warned by Kaa, who is summarily belabored with slapstick beatings and poundings, again and again. No heist is particularly difficult, as the money is always seen as sitting in a bucket next to Prince John, or gathered in chests around his bed as he sleeps.

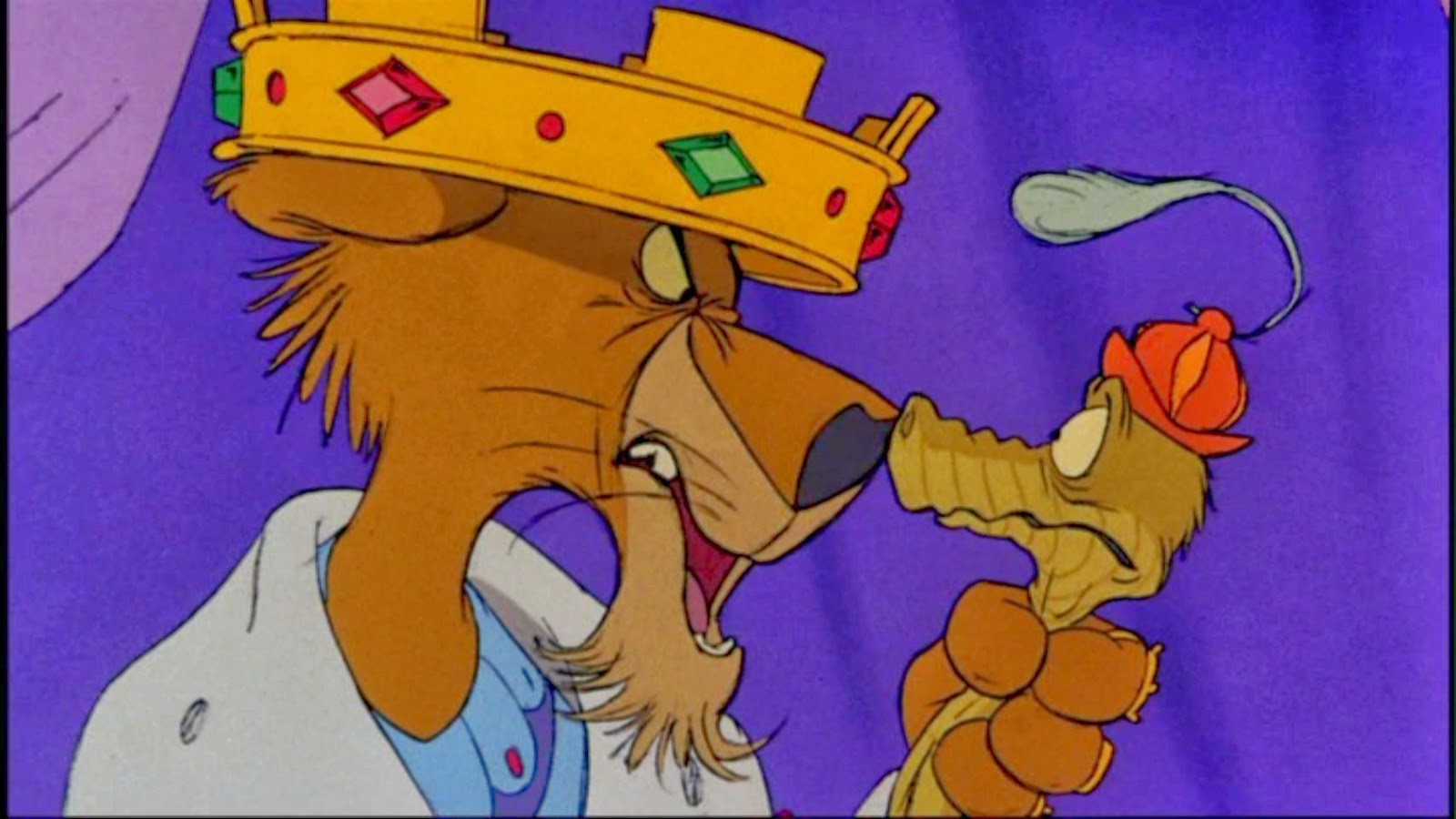

There is precisely one scene where Prince John scowls, and looks actually menacing. Otherwise, he is subject to a recurring bit of business where his crown slips down around his ears, he sucks his thumb, and whines for his mommy. Kaa is merely a flattering toady and a punching bag.

The Sheriff of Nottingham is a corrupt Southern sheriff, portrayed by the great Pat Buttram, who was Gene Autry’s sidekick, Mr. Haney in the television sitcom GREEN ACRES, and, most recently, Napoleon the butler-biting bloodhound from Disney’s ARISTOCATS. He may be the only real villain in the piece, as he shuffles along with a folksy and avuncular smile while he robs and pockets the last penny from children and churches.

In none of these cases did the writer actually do the work needed to establish character, motive, plot, or tension; consequently all the scenes are static, even those that should be been exciting scenes of chases and escapes, because nothing has any sense of danger, nothing is shown to be at stake.

The worst offense of all is the ending. Having reached the desired run time, the rooster narrator announces, without it being shown on screen, that King Richard had returned from overseas, and simply set everything right.

We then see Richard step through a door, laugh genially, say one line, and the camera pans over to Prince John, Hiss, and the Sheriff now wearing striped shirts, in a chain gang, breaking rocks on the rock pile, while a marriage carriage adorned with ribbons and flowers drives by, showing Robin and Marion off to their honeymoon, she in her wedding dress. A kiss. The end.

For the record, King Richard’s one line is “I now have an outlaw for an in-law.” This is witty enough, but it was the second time it was spoken, the first by Marion earlier in the film.

To be sure, the film is good hearted, and at times charming. Who does not like bunny children? But charm is not enough to carry the film. One needs humor, music, and most of all, a plot.

As for the humor, it is off kilter. Compare any scene here with an honestly funny scene, such as when the dwarves in SNOW WHITE are commanded by the sweetest of young girls to go wash up, and they approach the water trough with fear and trembling, having not bathed in years.

Let me pause to mention what makes the slapstick in this film so uncomedic and frankly uncomfortable. Normally, slapstick has some element of justice or retaliation to it: a toff has to be shown walking with his arrogant nose in the air in order to make it funny when he slips on a banana peel. Or, likewise, the stooge has to be shown doing something stupid or exasperating, chuckling and unrepentant, before Moe Howard twists his nose or pokes him in the eye. It is not funny if Curly says he is sorry before Moe yanks his hair. Likewise, Moe is so mean, it is a pleasure to see him dunked or squirted or swatted.

But there is no pleasure in seeing a sadist tormenting a cringing underling, when, as here, the underling is never shown doing anything wrong. In this story, Kaa threatens no innocent bunny-child, nor is he anything but flattering to his prince. In THE JUNGLE BOOK, in an exactly parallel scene, when he fibs to Shere Khan, and tries to mesmerize him, it is a satisfying moment of slapstick to see the kingly tiger casually slap him to the ground and poke him up his nose: he deserved it.

The slapstick here is too broad. When we see stone towers knocked aside and tents turned into juggernauts or balloons or whole armies defeated by an overweight chicken, this is no more improbable than a Chuck Jones short; but then, a scene later, how are we supposed to be worried when Robin is climbing a gate, or looks as if he might slip and fall into the moat?

After someone is dashed to the ground from a thousand feet, it is difficult thereafter to worry he might fall from a forty foot wall.

And if castle walls are make of cardboard, such that a brown bear can barrel through them unharmed, how it is that the prison walls are suddenly fearsome and implacable?

The humor in SNOW WHITE, where Dopey clowns around, or in SLEEPING BEAUTY, where three fairy stepmothers discover they know nothing of how mortals sew or bake, does not diminish the menace of evil queens or malefic fairies. Here, the thumb-sucking prince and all his soldiers are the butt of the joke. To be sure, having the bumbling Sergeant Garcia always be humiliated by dashing Zorro makes him no menace to our swashbuckler: but the whole might of the caballeros still forms a threat.

In an action story, the humor cannot violate the terms of the threat formed by the villain: in Disney’s ROBIN HOOD they do, and grossly so.

In the Errol Flynn version, the Sheriff of Nottingham is portrayed by the brilliant character actor Melville Cooper as a clownish braggart, and is honestly funny, but Claude Rains as Prince John exudes a quiet, charming menace and Basil Rathbone as Sir Guy of Gisbourne is the perfect archetype of a sneering and cruel swashbuckler villain. Fox Robin Hood from Disney has no real villains to face, and so can be no real hero. This lapse is due solely to the addition of slapstick comedy elements to the villains: had Prince John talked and acted like Shere Khan, no one would have doubted Robin would need a heroic heart to face him.

As for the music, the songs are remarkably unremarkable. There is a love song by Marion, perfectly sentimental and serviceable, that could be the Platonic Ideal of the most generic love song of all time: “Life is brief, but when it’s gone; love goes on and on.”

The scene is pretty to look at, and, in my opinion, worth watching in itself: against a glorious watercolor woodland backdrop, Robin and Marion walk by the running river under the moonlight, surrounded by clouds of fireflies. When he puts a flower on her finger as a promise of marriage, a firefly alights in it.

But I am reminded of a similar love song passage in BAMBI, with a song that, likewise, no one remembers. Taste in music differs, but the music here is more complex and complete, and the animation is shockingly superb, showing Walt’s genius. Bambi revisits the place of his mother’s death, but now with joy.

There is another song calling John a false king, and a third bemoaning the sorry state of Nottingham under the tyrant’s cruelty. Except that, as with each other story element, neither the falsehood of John’s claim to the crown, nor him making such a claim, nor the oppression and misery of the common folk (aside from the folksy sheriff stealing pennies from children) is onstage. The audience is simply supposed to remember the story from parallel scenes in the 1938 Errol Flynn version.

So the song lyrics are bland, but the whistling and yodeling by country singer Roger Miller are memorable. The aimless lyrics of “Oo-De-Lally” are charming and cheerful. If only the story had been set in the South, after the fashion of the DUKES OF HAZZARD, which it very strongly resembles, this could have been the theme song. You may find yourself humming along. Likewise, opening song, “Whistle Stop” is so catchy that a child hearing it in 1973 is probably whistling it to this day.

I have already waxed vexedly about the lapse of plot, but it behooves me to say the secret of how to write plots, to make the point clear:

Every action in a plot has a set up, to showing the aim of the action and what is at stake, shows the action, shows the consequences. As in golf, there a backswing, an strike, and a follow-through. To make a plot, the elements are connected as if by a chain, with the follow-through of the antagonist action being the set-up for the protagonist reaction, which, in turn, sets up the antagonist counter-reaction. Such links are crucial to action stories.

Better still if the stakes, both personal and public, get higher with each action and reaction, as when the real Robin Hood finds himself not only fighting for the freedom of Nottingham, but the hand of Marion.

Without these actions being linked to reactions, the tale is a vignette or slice of life. Vignettes are perfectly serviceable and legitimate for a coming-of-age tale like BAMBI, where the allure of the story is the protagonists’ discovery of the world around him, and finding his place in it. That tale is literally one voyage of discovery after another: a first step, a first word, a first friend, seeing the meadow and the grown stags for the first time, discovering death, enemies, adulthood, strength, romance, victory, princedom.

But a vignette also has a structure of one discovery following another. There is a Japanese name for writing vignettes, kishoutenketsu, which follow a discovery structure where the situation is established, we learn more about it, and resolution is seeing the larger picture that either reverses or illuminates the initial picture.

The drama in such a case comes not from the plot-motion but from the increasing stages of growth or discovery as the dramatic tableau is revealed. It is not merely one random or episodic event following but unlinked to the next.

If you find yourself in a tale where any scene could be swapped in place with any other, this is neither a vignette nor an action story.

Alas, Disney’s ROBIN HOOD is just such a tale.

Robin’s robbery of Prince John from his coach could have been swapped with this robbery from the bedchamber with no dialog changed, and likewise the archery tournament could have been put before or after. The scenes where adorable bunny children meet Robin or meet Marion could have been placed before or after any other scene. Even when Robin burns Prince John’s castle, and the Prince falls to his death could be moved anywhere, since he does not actually die, but merely falls in a moat and emerges dripping and spitting water.

This movie could have been five episodes from a television show, made in the days when syndicated episodes were made to be shown in any order, with all elements returned to their initial condition at the end of each episode, and nothing permanent lost or gained.

Now, the worst Disney film is still far likely to be better than any average film. It would be unfair not to close this review without mention and praise for its merits. The voice acting is brilliant, as ever.

The conceit that animals tell tales with all the characters as anthropoid animals is unique yet brilliant. One would think this charming wink to explain why beasts are playing all the roles would be commonplace, but I have never seen it elsewhere.

I cannot bring to mind another Disney film where there are no humans, only humanoid animals. There are talking animals aplenty in Disney films, but usually they are talking animals living in a human world. Even if the animals wear clothing and walk upright, as in GREAT MOUSE DETECTIVE, there is usually a larger human world under which the mouse-world secretly lives. Here, England is entirely Narnian, so to speak.

Whoever animated Kaa the Snake deserves a special mention, since he manages to gesture, to cross his arms, and shrug his shoulders, entirely without arm or shoulders. A similar cleverness was shown by the snake named Snake in the recent heist film THE BAD GUYS, but it was first done here.

Robin Hood himself is a delight. The animation and voice acting captures the looks and expression of a storybook swashbuckler, complete with charming Errol Flynn grin. The Maid Marion is a perfect vixen-version of Olivia de Havilland. The two of them, costumes and faces and gestures and so on, simply make a nice couple, and whenever they are on the screen, it is a delight.

But I cannot really recommend the film except to the youngest of children.

However, I can strongly recommend the 1938 THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD starring Errol Flynn and Alan Hale, as the thorough brilliance and craftsmanship of that film, splendid in spectacle and richly adorned via an immortal Erich Wolfgang Korngold filmscore, is beyond compare. This film with its shortcomings reminded me strongly of how much better that original was than I recalled.