Review: THE BOY AND THE HERON

THE BOY AND THE HERON is a 2023 film written and directed by the great Hayao Miyazaki, and produced by Studio Ghibli. This is to be Hayao Miyazaki’s last film, as have been every film of his since roughly 1997.

As most or all of his other films, this is a work of splendor, a fanfare of the spirit, plunging to depths and reaching heights where only great works of art dare tread. It earns highest recommendation.

It is, however, not an easy tale to unriddle, involving, as it does, themes hidden in symbols, visions and time paradox, and characters and events whose meaning is elusive.

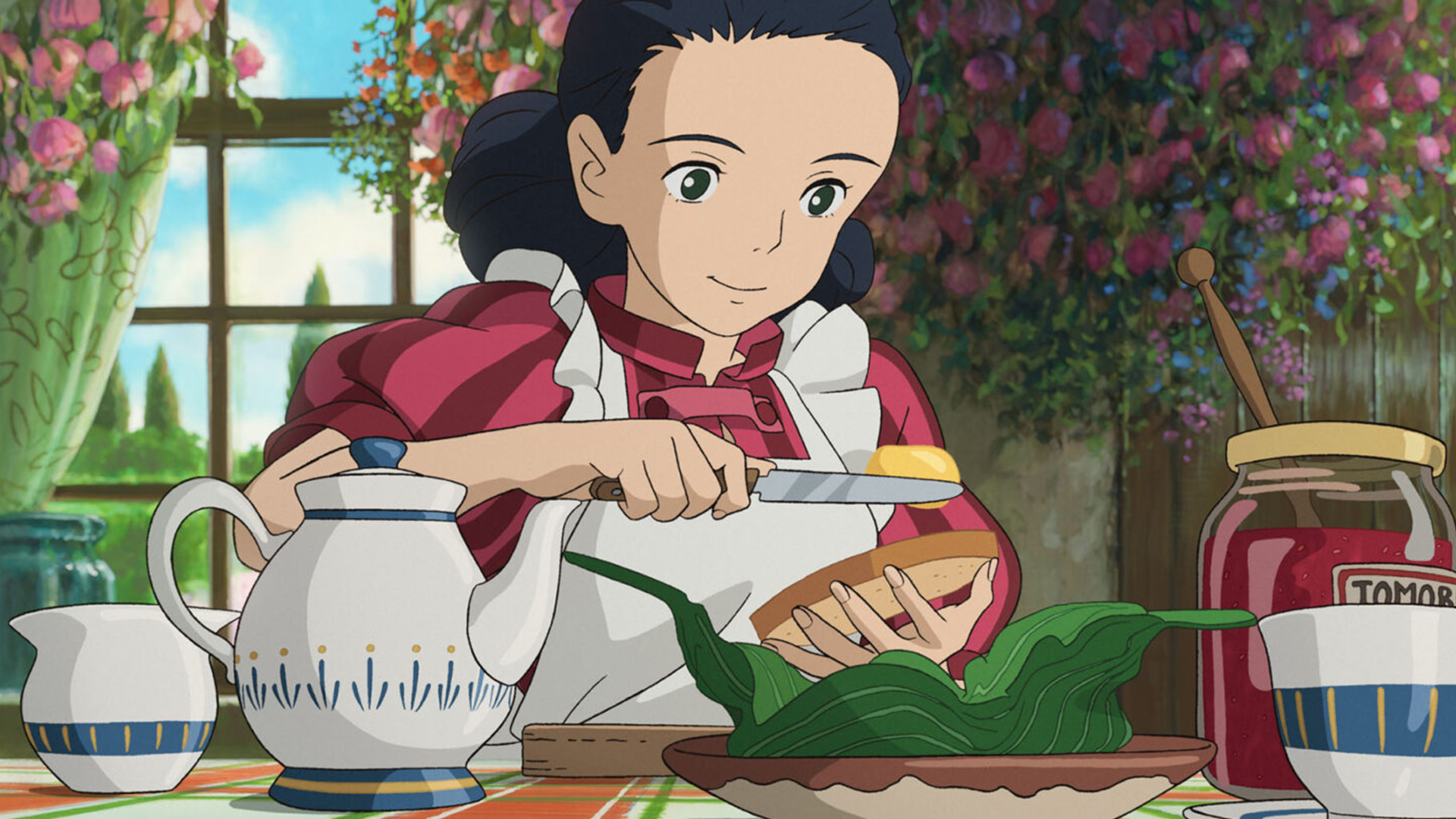

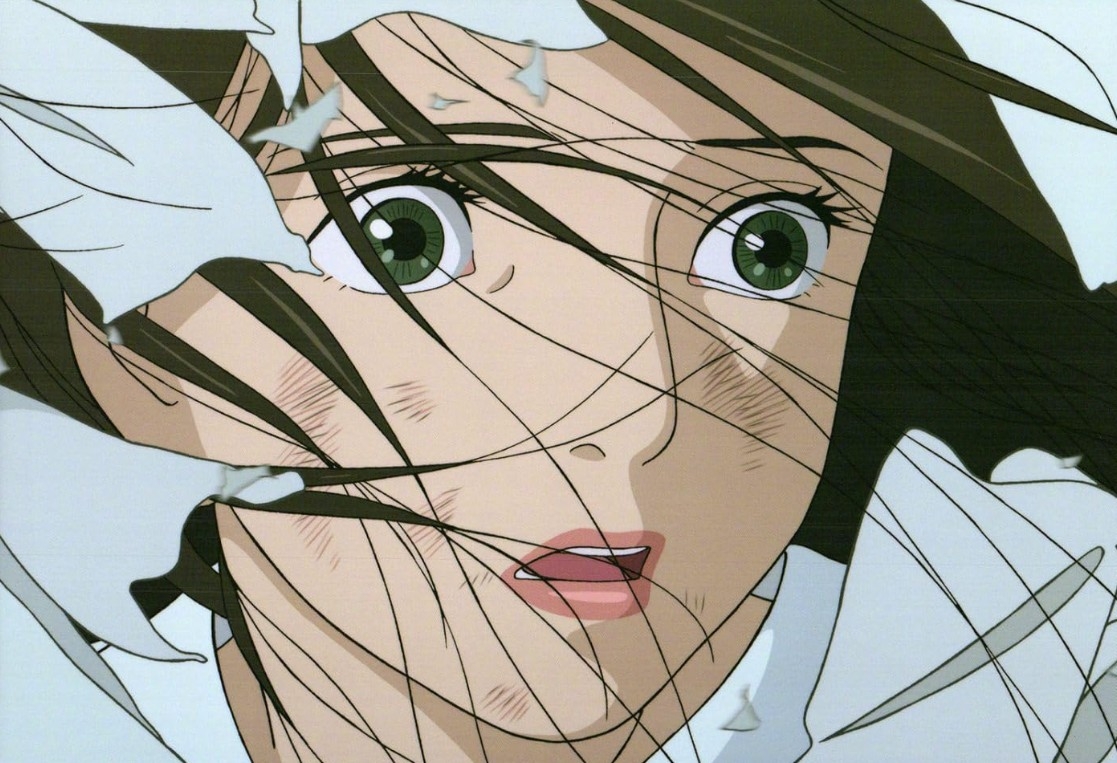

This film was seven years in production. It is claimed to be the most expensive film ever produced in Japan, and an awestruck examination of the richness of detail, of color and texture, motion and smoothness in the animation, including some sequences that can only be described as experimental or psychedelic, shows the money was not wasted.

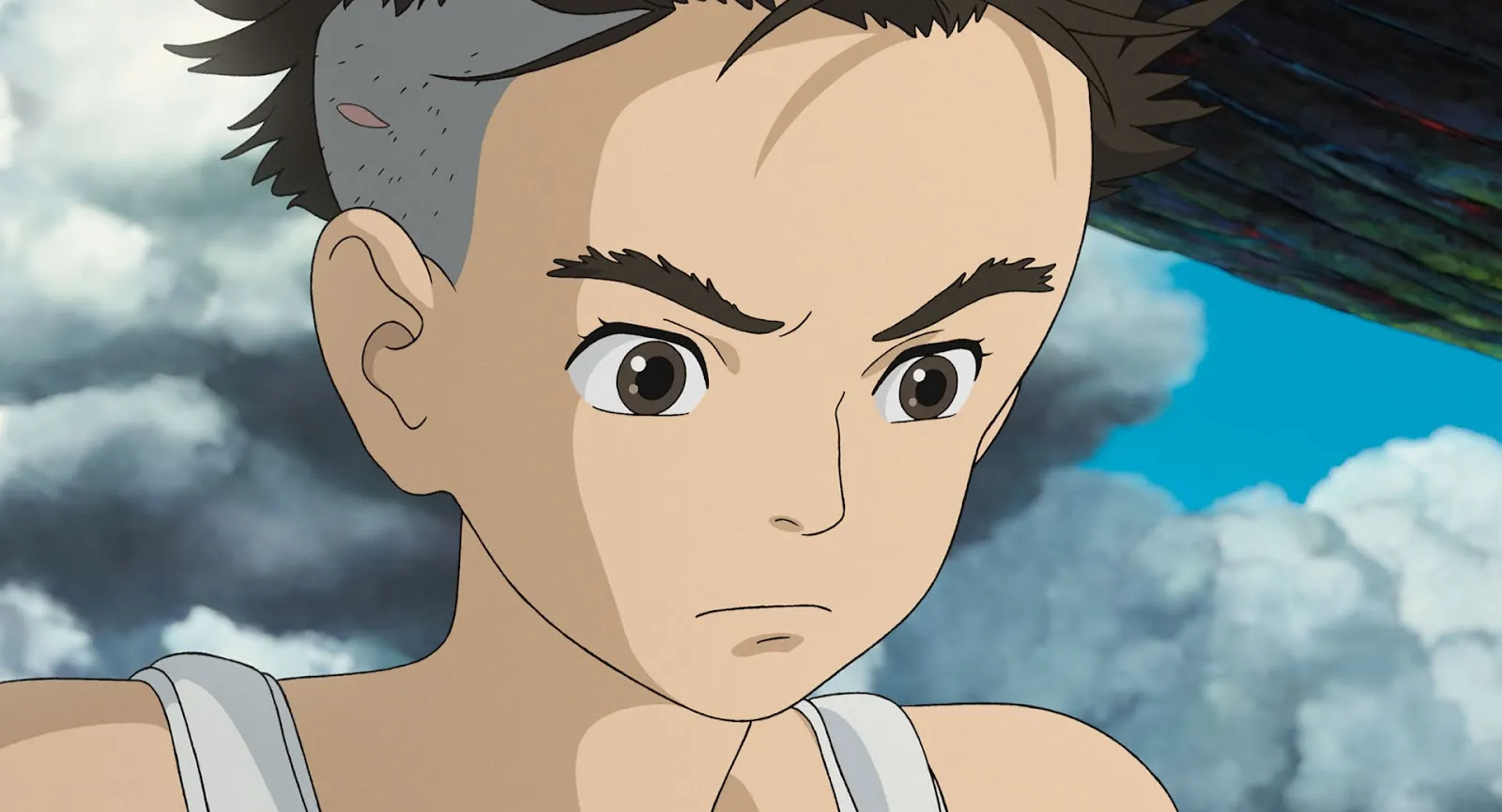

The tale concerns the grieving orphan Mahito Maki, whose mother Hisako was lost in a hospital fire during an air raid of World War Two. His father weds his dead wife’s twin sister, Natsuko, and the boy is evacuated to the maternal estate, staffed by a gaggle of comical housemaid crones, by turns sour and selfless.

Maki is withdrawn and curt, unable to adjust to his new stepmother, new surroundings, new school. After a fistfight with other schoolboys, he brains himself with a rock, perhaps to frame his attackers, perhaps to excuse himself from school.

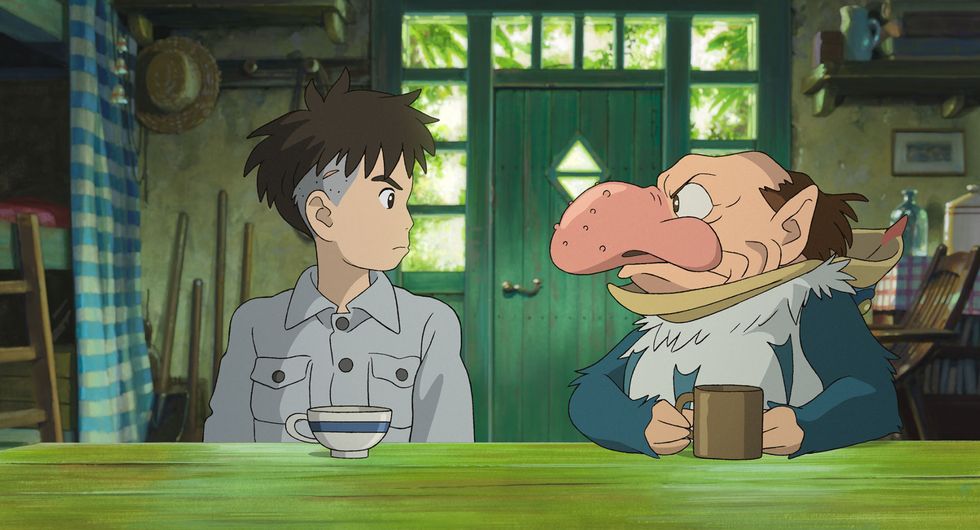

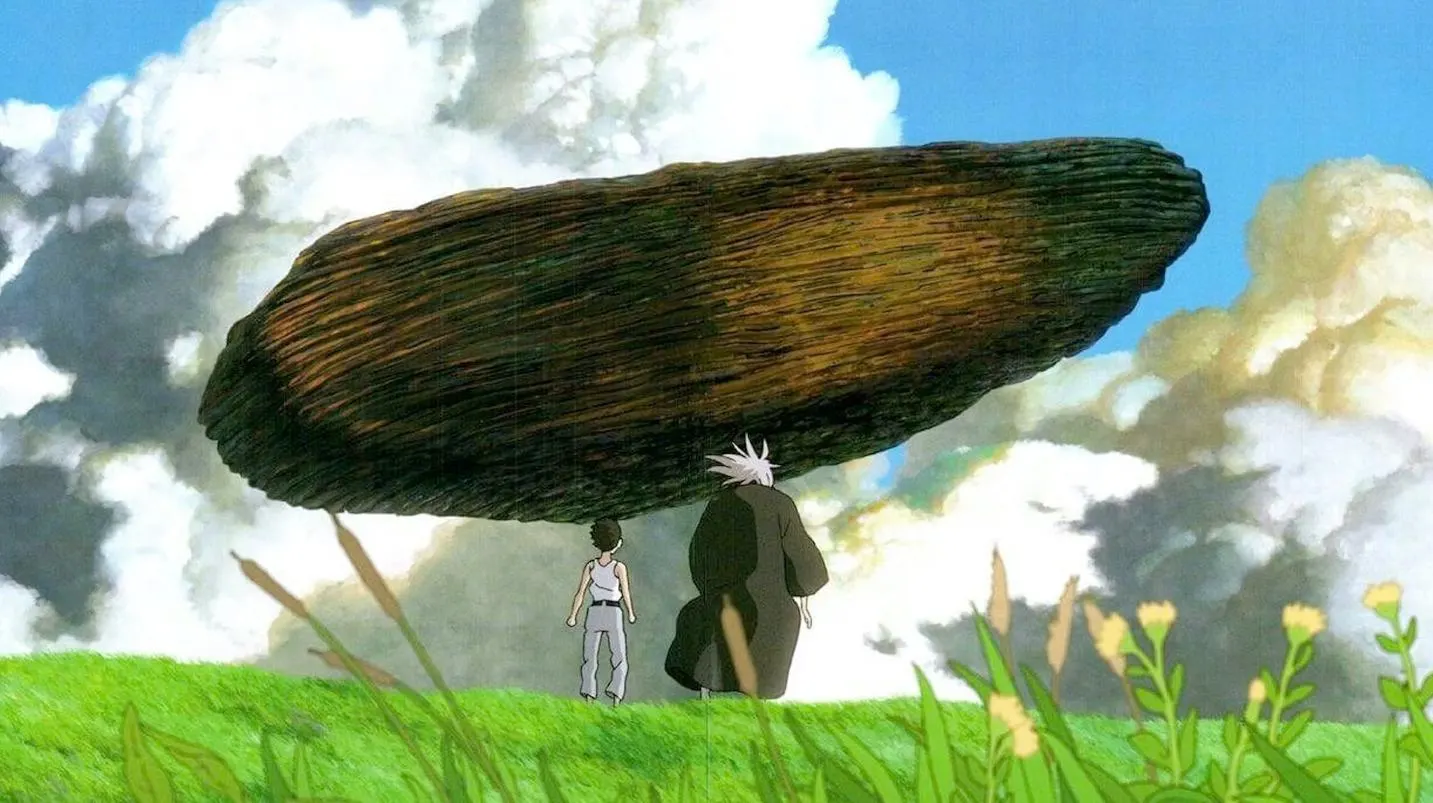

A gnome disguised as a gray heron attempts to lure the boy into the strange, abandoned tower erected long ago from a supernatural meteor by Maki’s great-granduncle, a man driven mad by reading too many books. He is told his presence is requested. It is hinted his mother is still alive within the tower.

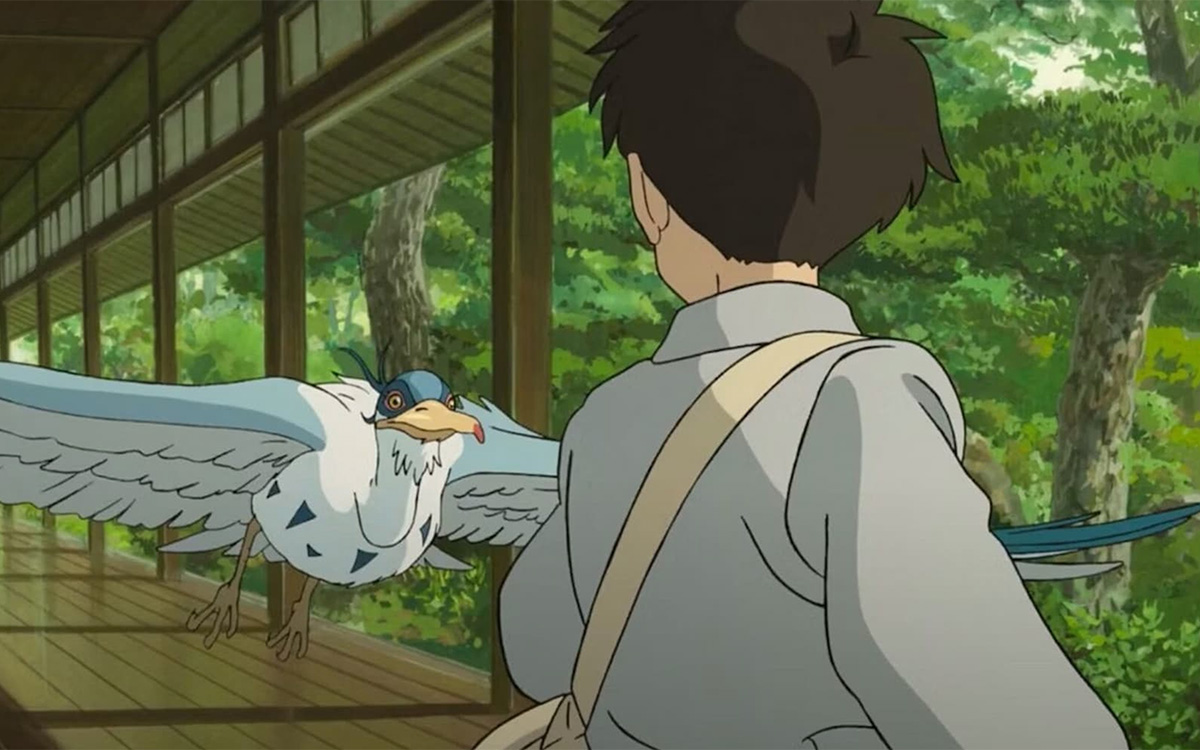

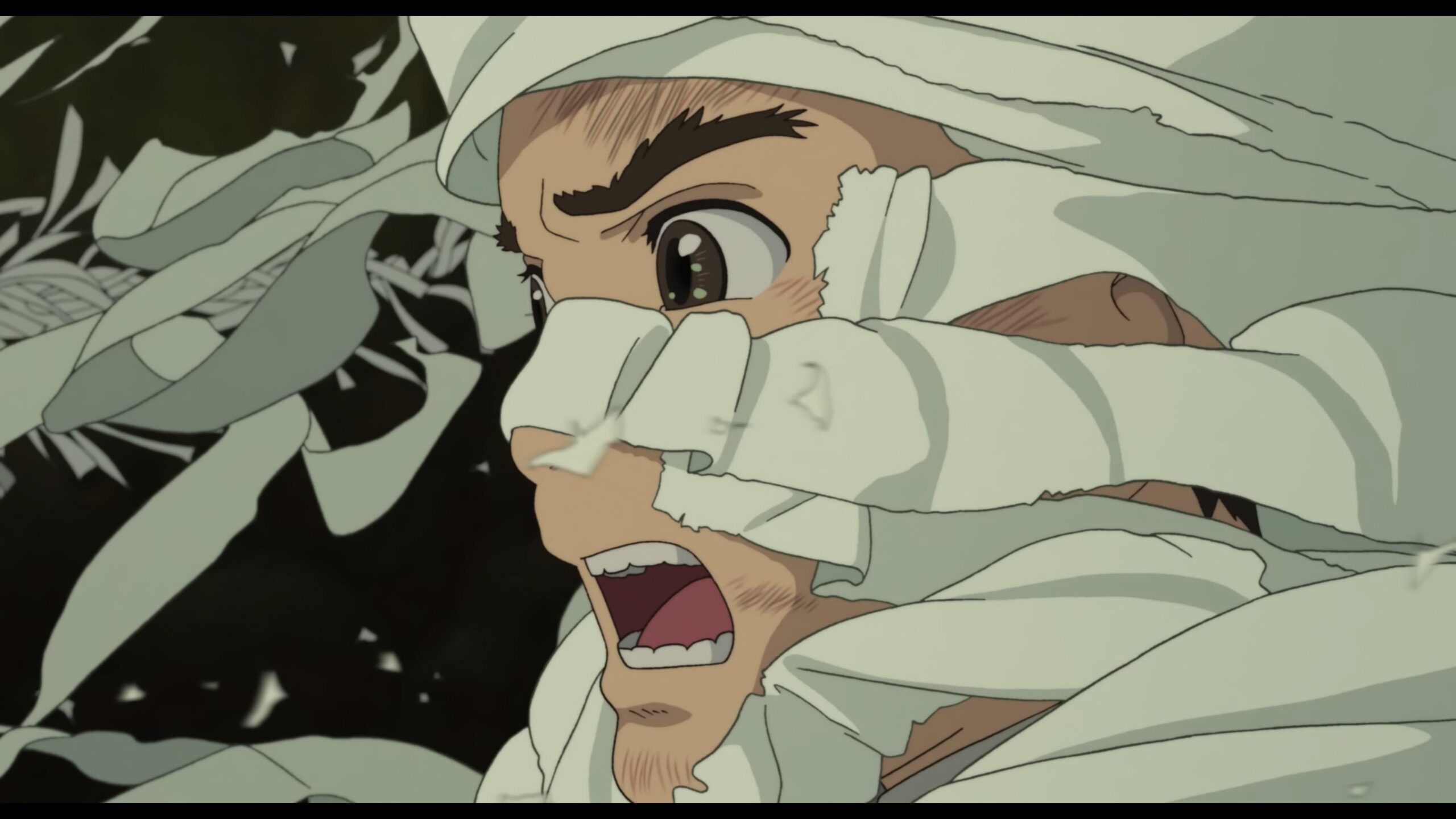

These eerie allurements fail at first, foiled by a whistling arrow (a kabura-ya, traditionally able to ward off evil influences) but when the heron enchants Maki’s pregnant stepmother to sleepwalk within the tower, Maki crafts a bow for himself, and crawls into the long-sealed structure, reluctantly followed by one of the crones, Kiriko.

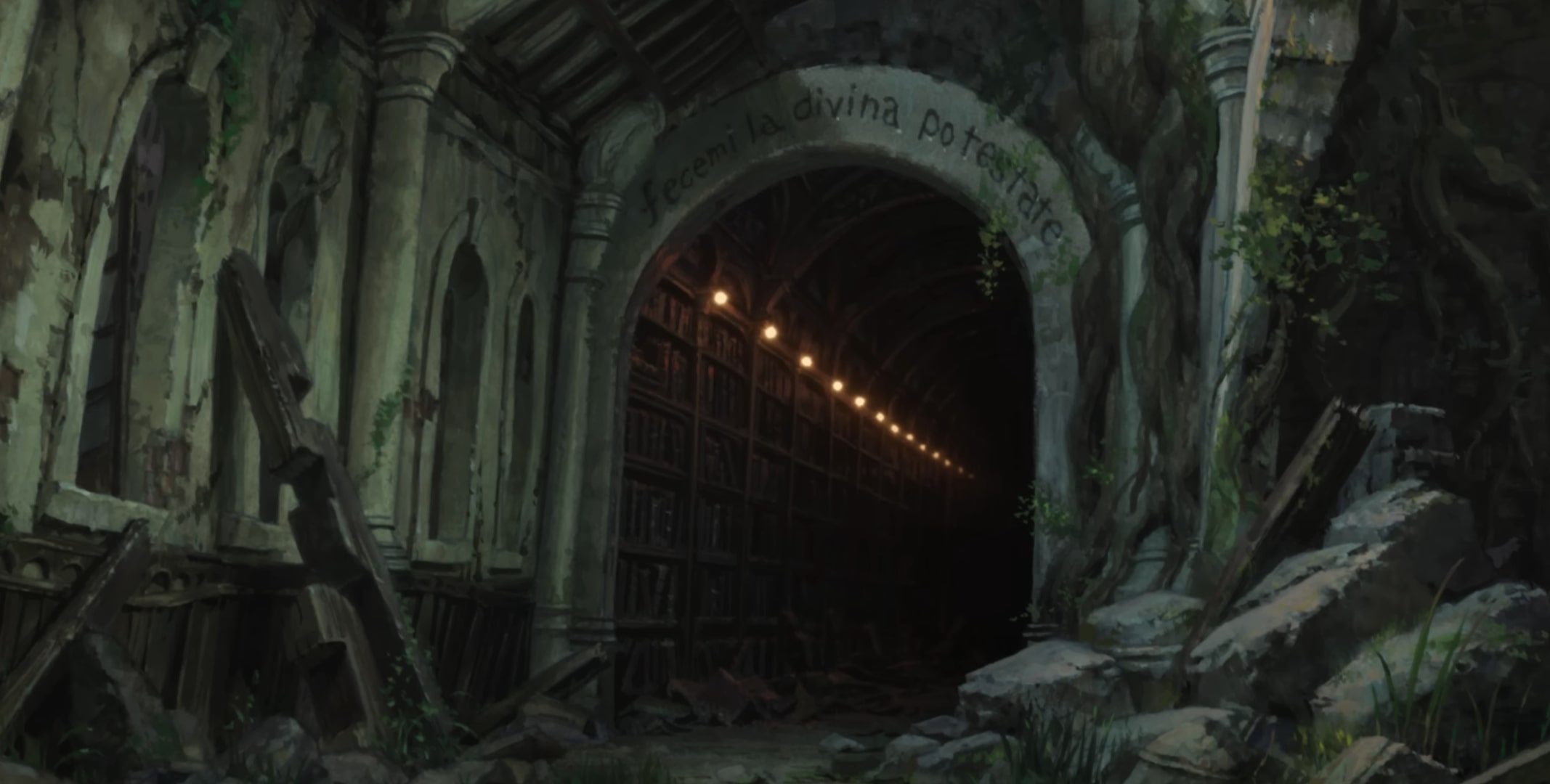

The tower entrance is inscribed with the words fecemi la divina potestate (“I was made by divine power”), a quote from Dante describing the infernal gates.

Maki’s arrow is enchanted by a feather stolen from the gray heron, and hence can strike and wound the heron’s beak. This mars the feathered coat that allows the gnome hidden within to assume heron shape, hindering his power of flight, and bringing him to heel. (Maki will later repair the cloak and befriend the gnome).

Maki reaches the center of the tower, where a cruel illusion of his mother melts away at his touch. The wizard appears on a balcony above, commands the gnome to guide Maki, and all below are then swallowed by the floor as by quicksand.

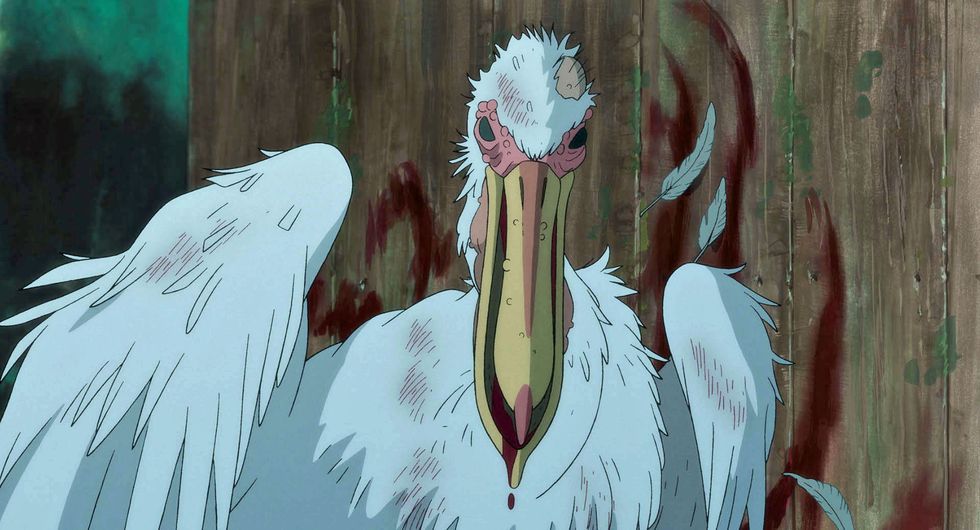

Below the tower are other realms, corridors through time, youthful versions of figures from Maki’s life. Here are spirits of children before birth, soul-eating pelicans, and man-eating parrots.

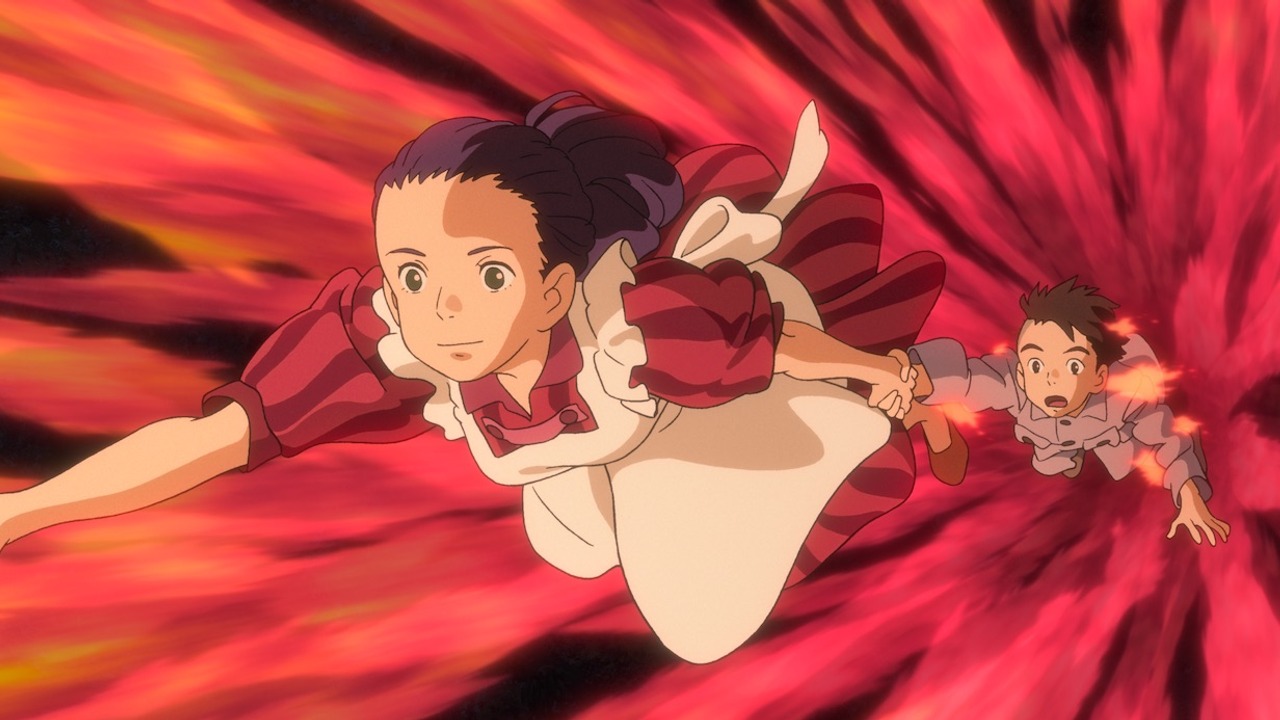

Aided in his search for his stepmother by a hard-bitten fisherwoman, and a pyrokinetic maiden, Maki confronts visions of unearthly beauty and hellish desolation, facing capture and menace, aided by unexpected benefactors.

Nothing is as it first seems. For example, after a fight to save the unborn, a wounded pelican explains that his people were brought into this world without a proper place prepared for them, and no food to eat. Only by preying on the unborn baby-souls can they survive.

Maki finds the stepmother enchanted in an eerie Shinto birthing chamber, but is rejected by her, and driven off by a snow storm paper dolls called shikigami.

The pyrokinetic maiden, a young girl who wandered into the inner worlds of the mystic tower at the turn of the century, aids him in finding the time corridor to return Maki to his proper world and year, but he refuses, returning to make a final attempt to save his stepmother.

Maki learns this inner world is artificial, created by the wizard, meant to be utopia, but marred by malice of all the souls invited or trapped within.

In a climax, the wizard reveals he is Maki’s ancestor, and seeks to pass to him the power of the worlds within the tower, and make him master of his own reality. He shows Maki the set of unsteady blocks that must be balanced daily for the inner worlds to escape destruction, and says Maki can perfect what the wizard began. Maki points at the scar on his head, the sign of his own internal malice, and refuses.

Meanwhile, the bold but bombastic general of the parrot army seeks the legacy for himself, to rule the inner worlds and save his people, but, alas, he suffers the harsh fate commonly seen to befall militarists in Miyazaki films.

When the tower collapses, the parrots return in a gush of feathers to their unenchanted forms, the pyrokinetic maiden returns through time to the fate set for her, happily, without regret, and the stern and youthful fisherwoman returns to her earthly form as a comical old crone servant.

As for Maki, he then choses how to live.

The characters are as nuanced, draw with verisimilitude and solidity. Their concerns and motives are realistic, sometimes obscure, sometimes obvious, sometimes wrestling with each other. Maki’s relation with his stepmother, for example, is made more complicated by the fact that she looks just like his dead mother, and neither shows warmth to the other. As another example, the petty bitterness surrounding wartime shortages of cigarettes and groceries is noted at the opening of the film, and reflected in the anthropophagic starvation of the pelicans and parrots in the otherworld within the tower. Maki is stoic and undemonstrative, his reactions largely unspoken.

The backgrounds, settings, costumes and so on are so perfectly animated that description falls silent. Both the 1930’s Japan and the otherworld of oceans, shadows, monoliths and birds are exquisitely drawn. The manor house is a curious mix of Eastern and Western styles and luxuries. Even such small things as the way a carriage rocks under the weight of a passenger stepping aboard, or a bed sinks, are overlooked in lesser animated films. Here, every dewdrop of every blade of grass is visible, and every blade sways when the wind blows. If you saw the film neither subtitled nor dubbed, and understood not a single word, the visual feast would still please and overwhelm.

The meaning of the film is not likely to be seen in one viewing. It is perfectly enjoyable on the surface level, as an adventure, akin to SPIRITED AWAY, of venturing into perils of Elfland to retrieve an enchanted relative, but there may be reflections of deeper themes.

Considering Maki to be a youth of wartime Japan, the absurdly unsteady toy-blocks needed to keep the mystic tower of many worlds erect may reflect the temptation of the younger generation to follow in the crumbling bushido tradition of the military Imperium; or perhaps may reflect Miyazaki’s own meditation on by whose hands his lifework and legacy of Studio Ghibli will be carried on, or perhaps may reflect the unsteadiness of any young man emerging from a time of mourning, tempted to retreat into imaginary worlds, and flee the real.

In Japan, the film is called Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka (lit., What Life To Choose?). The 1937 novel of the same name by Genzaburō Yoshino is briefly seen in the film, shares a theme with it, but this story is not based on that novel.

The Japanese audience, however, may see a deeper meaning in the reference to Genzaburō Yoshino’s book. The book was one of the Nihon Shokokumin Bunko (Library for the Young) series, meant to oppose the rising nationalism and fascism of 1930’s Japan with Western ideas of liberty and progress to the young. Children’s books were not censored at the time. As the name implies, the theme of this and other books in the library touched on how to select what world should strive to make, given that the building materials of life include a past of malice, hardship and woe.

The plot is episodic, dreamlike, even disjointed, with certain elements simply never explained but with an understated thematic unity, as Maki wrestles with the grief of losing his mother.

It is difficult compare genius with genius, but this film matches even the high standards set by the several masterpieces he has created. On the other hand, it is more cerebral and opaque than some of his other films, and the themes and meanings may not be clear to a casual first viewing.

Very highly recommended.