Conan: The Devil in Iron

“For every beast and for every man there is a trap he will not escape”

The Devil in Iron was published in the August 1934 issue of Weird Tales, several months after the previous story, Queen of the Black Coast. It is the eleventh published story in the Conan canon.

We have reached the halfway mark of the published Conan stories completed by Robert E. Howard.

Howard here recycles elements of his own previous stories – there is a magic blade as in Phoenix on the Sword, the sole bane of an otherwise invulnerable eldritch monster, who is a resurrected necromancer as in The Black Colossus. He resurrects his ancient capital: a haunted city of greenish stone existing without fields or pastures, inhabited by dream-addled sleepwalkers as seen in Xuthal of the Dusk; he is a metal statue raised in grim mockery of life as in Iron Shadows in the Moon.

Conan sees the eldritch backstory of the foe in a convenient vision, as he likewise did in Queen of the Black Coast; and Conan’s sole motive here is neither loot, revenge, or love of adventure, but the raw lascivious lust as was on display in Frost Giant’s Daughter.

One assumes barbarians prefer blondes.

In previous Conan tales, I have complimented Howard’s lyricism, his well knit plots, his adroit use of narrative structure. Here, the evidence of his talent is muted. This reads more like one of the pastiches or homages of Conan by later writers.

While enjoyable, it is, frankly, not one of Robert E Howard’s better efforts.

Even the theme that barbarism ennobles the savage because he is free of the softening and corrupting influences of civilization is muted in this story, mentioned only in passing. We have no scenes of the barbarian brooding on the nature of fate or the indifference of the gods. Instead, Conan is subject to a fear of the supernatural Howard identifies as typical of savages, moreso in this tale than seen heretofore.

To see our hero flee in fear is rare in a Conan story, but it is useful to remember that the Conan tales all take place within the Lovecraftian background universe of inhuman elder gods and indifferent abysses of time and space.

Conan spends a fair amount of the climax running and hiding, which is unusual for him, but, when trapped, his fear evaporates, and he faces death with a clear-eyed stoicism: the only moment I found truly memorable in what was otherwise an undistinguished story.

However, this author on his days of more modest accomplishments is more accomplished than many an author on his best day. Mediocre work from Howard’s pen still sparkles and leaps with energy and drama.

Let us summarize the plot, before noting what else is noteworthy in the work.

Howard sets his mood and theme in the terse description of his opening lines:

THE FISHERMAN loosened his knife in its scabbard. The gesture was instinctive, for what he feared was nothing a knife could slay, not even the saw-edged crescent blade of the Yuetshi that could disembowel a man with an upward stroke. Neither man nor beast threatened him in the solitude which brooded over the castellated isle of Xapur.

Irony abounds. He is, as it turns out, threatened by neither man nor beast in the unnatural, brooding ruins of Xapur. What he fears is indeed nothing a knife could slay, being invulnerable. But the horror does after all die by a knife-blow in the end, one forged of no earthly metal.

The fisherman is given no name, as his role is the sad and brief one of being tempted by simple greed into picking up the bejeweled dagger, forged of unearthly metal. Thus he unwittingly unlocks an ancient evil from its eons-long imprisonment. He does not outlast the opening scene.

The second chapter introduces the second plotline: in the reaches of a great oriental empire of Turan surrounding the inland sea, one band of savage steppe-dwelling Kozaks , ruthless raiders of insolent audacity, has escaped all attempts to capture and kill its bold new leader, Conan. Turan is the Hyborian version of Persia, and the Kozaks are Hyborian Cossacks.

The local military governor, named Lord Agha, menaces by the displeasure of the king, conspires with his sinister minister to lure Conan into a deserted island just off the coast from his current camp, whose sheer sides will prevent escape while he is hunted down by bowmen like a lion at bay.

This island just so happens to be Xapur, crowned by haunted ruins.

To this end, the defiant but lovely yet scantily-clad blonde captive from the northern lands, Octavia, a nobleman’s daughter, now a mere slavegirl, is commanded to favor Conan with smoldering looks and come-hither winks during an upcoming parley, and, later, a spy will feed him the false information that she has escaped and is hiding on that island.

Like Achilles having a vulnerable spot in his heel, or Siegfried in his back, Conan’s weakness is for women. He will surely go alone, for no man takes a war band with him when he goes wooing or bride-napping.

Why her? The sinister minister gives the reason:

“Her vitality and substantial figure should appeal to him more vividly than would one of the doll-like beauties of your seraglio.”

Being a lovely but scantily clad defiant blonde captive, Octavia defies her captors with her lovely eyes flashing angrily, and her lovely bosom heaving curvaceously, but the threat of torture saps her will to resist, at least until the next chapter.

In the next chapter, she is even more lovely, defiant, and scantily-clad than before, since she escapes from a harem window on a rope made of knotted tapestries, steals a pony, flees through swamp to shore, leaving the pony to flounder in the morass, and swims the ocean to a sheer-sided island just off shore, a dripping white goddess in the dim starlight.

Before anyone dismisses the coincidence that our lovely love interest just to happens to escape and flee to the very island the false report fed to Conan reported she had escaped and fled, keep in mind two things:

First, her erstwhile masters discussed the possibility of her escaping right before her ears, and perhaps put the idea in her head. The evil minister, remember, picked her out of the other slavegirls in the seraglio because of her “vitality” (among other assets) — in other words, the author establishes even before she comes on stage that she is the kind of girl likely to attempt escape. Conan would not have believed the false report that she had escaped had he seen a girl lacking this particular vitality.

Second, the bad guys are lying in wait in the reed marshes off the shore of that very island, because that is the plan. So when she escapes from the bad guys, she naturally goes toward the best hiding spot in the area, the reed marshes, and upon seeing an island in the distance, goes there. It is not as if she picked the island out of an entire archipelago of choices.

Of course, once on the island, she pauses a moment to reflect on Conan, with whom she had earlier been forced to flirt:

His burning gaze had frightened and humiliated her, but his cleanly elemental fierceness set him above Jelal Khan, a monster such as only an overly opulent civilization can produce.

Naturally, his elemental cleanness sets him above civilized corruption. One assumes blondes prefer barbarians.

She steps barefoot into the pitch-black woods and is immediately captured.

In the fourth chapter, we finally meet Conan. Lord Agha and his archers watch from ambush as Conan, rowing alone, approaches the deserted island, as planned.

The man in the boat was a picturesque figure. A crimson scarf was knotted about his head; his wide silk breeches, of flaming hue, were upheld by a broad sash, which likewise supported a scimitar in a shagreen scabbard. His gilt-worked leather boots suggested the horseman rather than the seaman, but he handled his boat with skill. Through his widely open white silk shirt showed his broad, muscular breast, burned brown by the sun.

This is a far cry from the furry loincloth look popularized by Frank Frazetta illustrations. Conan here is dressed like Douglas Fairbanks, Jr, down to the red headscarf and the scimitar:

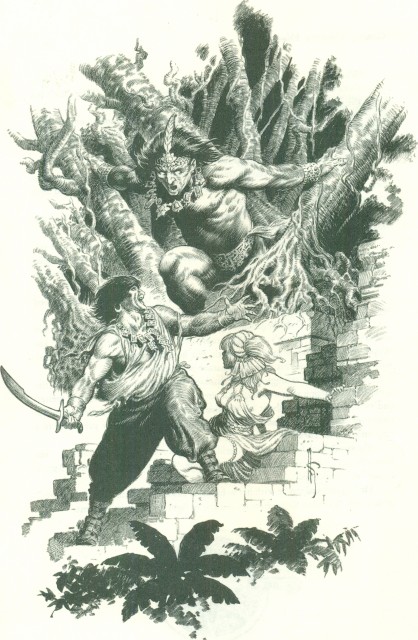

Conan comes across the ruins in the place he expects, but now the ancient walls and towers are restored and furnished and inhabited. Conan is smitten with terror. He races back to the cliffside to depart the island and all eastern lands, but then spies a scented scrap of silk torn from Octavia in her struggles. Conan is smitten by lust.

Desire for the yellow-haired woman vied with a sullen, primordial rage at whoever had taken her. His human passion fought down his ultra-human fears …

He turns and scales the walls of the reincarnated city, following her footprints.

Stealing into an open window and through an upper chamber, he comes across a slender brunette with languid eyes. She is draped across her sleeping couch, unclad save for a wisp of silk about her supple hips.

Instead of raising an alarm at the sight of the barbarian stalking through her bedchamber, Yateli (so she named herself) murmurs in distracted, drowsy tones about a dream she had that she had been killed, and her city burned.

The girl invites Conan to love her, twines her shapely arms about his massive neck, but falls asleep in mid kiss.

Perturbed, he departs, and in the corridors and chambers beyond he finds other figures slumbering as if drugged among the opulence of ancient treasures, including skins and rugs made of beasts long extinct.

In chapter five, Conan come upon a giant serpent slumbering on a throne, and overhears the voice of Khosatral Khel, the necromancer and god-king of this long lost realm of Dagon.

At that voice, Conan falls into a trance wherein he sees the origin and early triumphs of Khel, and the fate of the city and all its peoples, once dead, now revived after sunset to a hideous mockery of life.

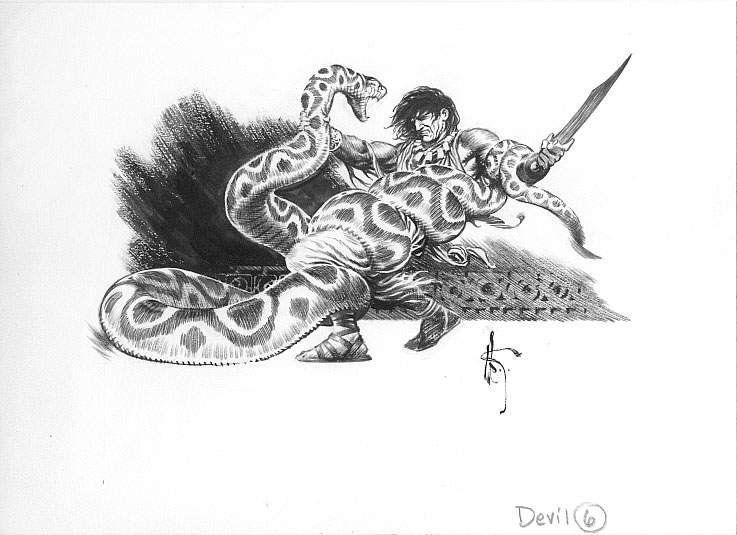

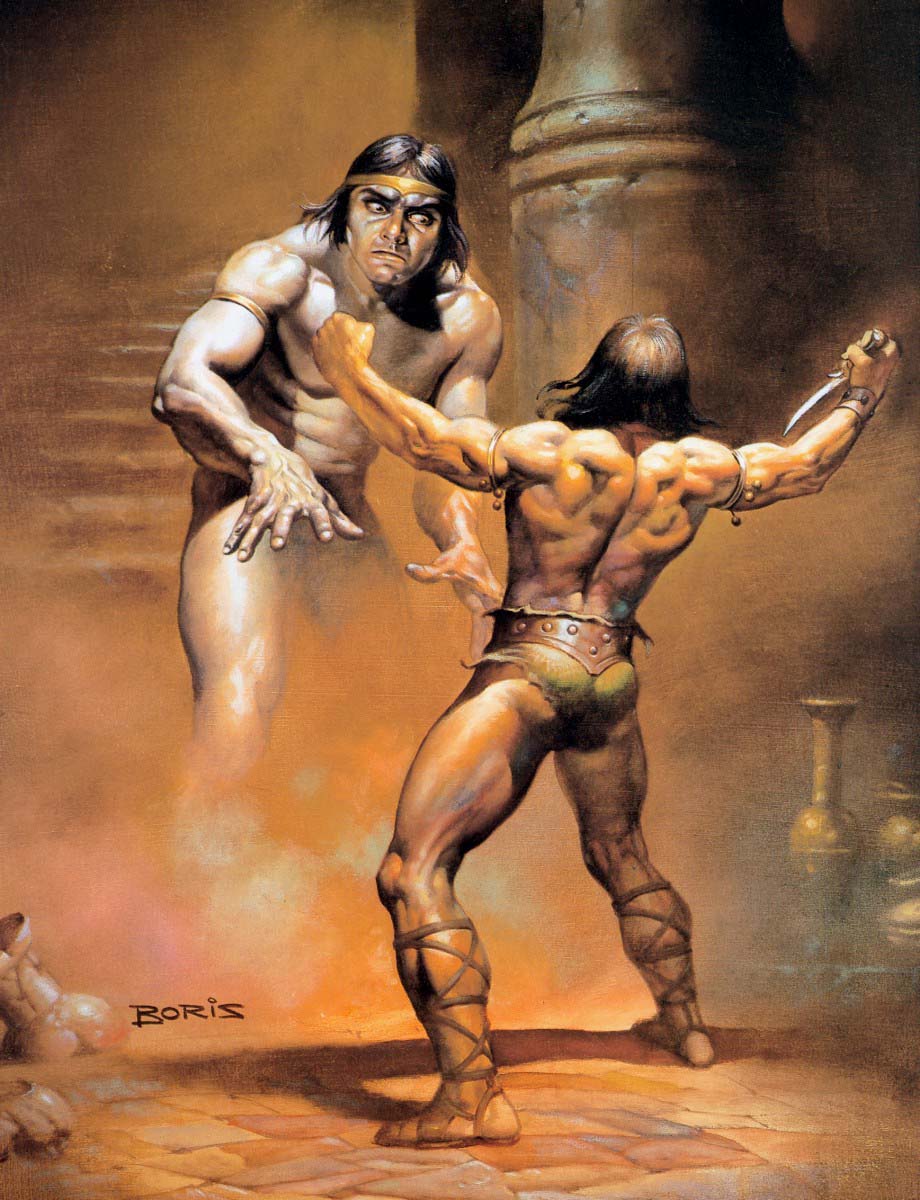

In the final chapter is the fight scenes and payoff. Conan is outmatched by Khel and gets badly battered. He flees. Conan fights a giant snake guarding the magic dagger. Lord Agha’s men get slaughtered by Khel. Lord Agha and Conan fight with scimitars. Finally, Conan faces Khel, and, despite the impossible odds, finds the one weakness to which the monstrosity is vulnerable.

Khel is one of the few extra-terrestrial monsters of the Cthulhu Mythos who has a human shape: he forced himself into a manlike body of solid iron (hence the title of the yarn). After death, he returns to his primordial shapeless form too hideous to be described, and the city and all its dreaming inhabitants, the dark haired women and shave-pated men, vanish like dreams back into their graves.

Now Conan claims his prize, forcing his savage kisses on Octavia, who is reluctant at first, but the barbarian promises to gather his Cossack horde and burn Lord Agha’s home city as a love-lamp to light her way to his tent.

There is not much to say about this story that has not already been said in the previous stories from which this material is being recycled. The city of Xapur is interesting mainly because the idea of reincarnating a dead city and resurrecting everyone inside it has a nightmarish magnitude hard to equal.

The theme of an ancient city that is a sealed trap for its inhabitants is a theme Howard will revisits in Red Nails, to far greater effect, for there the peoples did it and are doing it to themselves, and likewise for the drug-addled city dwellers of Xuthal in the Dusk. Here, by way of contrast, the city dwellers are some sort of ghost or memory returned to life by their god-king.

The females in the other Conan tales, while clearly not his match nor meant to be, usually have some sort of spark of confidence or spunk, and will cut Conan free from ropes when he is caught, or mind his wounds when he is fallen.

Octavia is spunky enough, to be sure, to spit her northern blonde defiance at sinister swarthy eastern men, but she interrupts Conan when he is trying to sneak past a giant snake; a bit of slapstick that nearly gets him killed. This is after being told to stay put and clam up. Likewise, Octavia is otherwise kidnapped and carried around like a child, or led by the wrist like a truant schoolgirl.

On the other hand, since Conan is chasing her because of her sexual appeal, not her personality, so the story does not need her to have much of one.

I have read stories (indeed, far, far too many stories) particularly sword and sorcery yarns penned by parochial modern pens, where the female lead has a great deal of some quality they call “agency”, but having no feminine qualities at all, no recognizably human qualities, and no appeal, sexual or otherwise.

A damsel who is actually in distress, and who actually needs a brawny barbarian to rescue her from an unearthly evil, is a little refreshing: and how many girls get a man to promise to burn a city for her? A lady should be flattered by such attentions.

Khel and Agha also have relatively little personality, but they play their parts well enough. There are no defiant speeches from Khel as we might hear from Thoth-Amon or Tsotha-lanti.

The eerie, even bathetic, backstory of a monster like the winged ape-creature brooding over a similar ancient site of ruins in Queen of the Black Coast is not present in Khel’s backstory, albeit the same sense of deep time is present.

The final interesting point to note is this: our nameless fisherman has a second purpose in the brief opening scene, aside from the Redshirt role of dying onstage to inform the reader of the monster’s danger.

It is only mentioned in passing, but the second purpose is significant: the fisherman is the poverty-stricken and wretched descendant of a one-great race of conquerors who had ruled this region of the inland sea long ago, in ages now forgotten, who had swept aside the last generation of the Dagonians, the earlier peoples, even more ancient, who had been sorcerers and kings ruled by a demigod.

The mood of melancholy fatalism is never far from any honest portrayal of the pagan worldview.

Likewise, the dizzying sense of mankind lost in the appalling vastnesses of geological time and in the infinities of astronomical space, is the particular province of the modern secular worldview.

The elder gods of Lovecraft come from distant worlds or other dimensions, just as the Titans from primordial chaos, or the Frost Giants from the primal ice, arose in earlier days before the gods men know.

The tales of Howard, like many others in the Lovecraft circle, are remembered and celebrated to this day because they are the first literature to capture that peculiarly modern return to pagan despair which comes from the lack of Christian hope.

Not even the fashionable nihilistic stories of the mainstream literati could touch this modern theme of the littleness of man in the universe, because it requires a science fictional or fantastic setting to portray things astronomically remote or geologically ancient.

Other critics might accuse Howard of historical inaccuracy of what real barbarians might be like, but no one should fault him for his accuracy of what the grim sadness of the world before the rise of Christendom was like.

It is the unfortunate fate of this tale that I read it after Queen of the Black Coast. The contrast in quality perhaps colors my expectations.

Were this the first Conan story a reader ever encounters, he would no dount be deeply impressed by the weird and striking effect of a barbarian anti-hero moving amid decaying civilizations built atop the unquiet ghosts and memory of eldritch, archaic evils which have the power to spring to life during a brief midnight hour, only to be driven back by brawn and sinew of the bold adventurer, a man who lives for the pleasures of the day, wine, women, song, and the savage and brutal clash of bloody arms.

This story is like many other Conan stories, but there are no stories like Conan stories, not even those penned by his most faithful imitators.